|

|

1 LP -

411 731-1 - (p) 1984

|

|

| 1 CD -

411 731-2 - (p) 1984 |

|

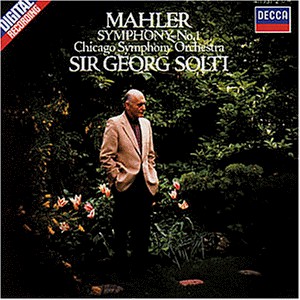

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony No. 1 in

D Major

|

|

55' 59" |

|

- Langsam,

Schleppend · Wie Ein Naturlaut

|

15' 45" |

|

|

| - Kräftig bewegt,

doch nicht zu schnell |

7' 44" |

|

|

| - Feierlich und

gemessen, ohne zu schleppen |

11' 34" |

|

|

| -

Stürmisch bewegt |

20' 50" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Chicago

Symphony Orchestra |

|

| Sir

Georg SOLTI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Orchestra

Hall, Chicago (USA) - ottobre 1983 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

James

Mallinson |

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

James

Lock |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Decca

| 411 731-1 | (1 LP) | durata 55'

59" | (p) 1984 | Digitale

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Decca

| 411 731-2 | (1 CD) | durata 55'

59" | (p) 1984 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

(c)

1984, The Decca Record Company

Limited, London

|

|

|

|

|

The startling

originality of Mahler’s

First Symphony earned him

both hostility and ridicule

when he conducted its first

performance in Budapest on

20 November 1889, reactions

which his music was to

provoke for the rest of his

life; for while his

interpretative genius as a

conductor of other people’s

music was instantly

appreciated by critics and

public alike, very few

listeners were able to see

beyond the uncomfortable

innovations of his own music

to the unique vision that

lay behind it.

It has only very recently

become clear that the

Symphony as we know it did

not reach its final form

until shortly before

publication in 1899. The

work, which Mahler had begun

as early as 1884, was

entitled ‘Symphonic Poem’ at

its Budapest premiere and

consisted then of five

movements. The original

second movement was soon

discarded (an Andante

entitled ‘Blumine’, or

‘Flower piece’,

it came to light again in

1967), and in the following

years Mahler expanded the

orchestration and revised

the work to such an extent

that hardly a bar was left

untouched. The number of

horns was increased from

four to seven and a cor

anglais and second timpanist

were added, as well as a

fifth trumpet and a fourth

trombone to reinforce the

horns in the coda of the

finale. What is significant,

however, is that apart from

the removal of the second

movement none of these

revisions affected the

musical content or structure

of the Symphony. In the ten

years between its first

performance and its final

revision for publication

Mahler had not only attained

the summit of his conducting

career (he had been

appointed Director of the

Vienna Opera in 1897) but

had also composed the Second

and Third Symphonies; his

awareness of his own

creative personality must

have grown immeasurably, and

increased experience meant

that he would now be

confident of being able to

express his musical ideas

with the most direct and

economical orchestral means.

The first movement's slow

introduction plunges us

straight into Mahler’s

unmistakable sound world as

stylized bird-calls and

distant military fanfares

gradually emerge from a

sustained A scored for

string harmonics. The impact

of such images in Mahler’s

music is constantly enhanced

by the apparently reckless

way in which he juxtaposes

them, creating immediate

tensions between our varied

reactions to different

musical styles. Thus in the

second movement a rough-hewn

peasant Ländler is

contrasted with a Trio

which, half-affectionately

and half-ironically, evokes

the sentimentality of urban

popular music. The third

movement - the greatest

cause of scandal for

Mahler’s contemporaries -

carries this mixture of

disparate elements to an

extreme as episodes of

deliberately vulgar

dance-band music (marked

‘With parody’) break into a

grotesquely-scored minor-key

canon on Frère Jacques

(or rather, its German

equivalent Bruder Martin).

The task of the finale - the

longest movement - is to

weld these elements into a

whole. The despairing F

minor material which had

briefly threatened the

spring-like freshness of the

first movement returns and

now threatens to dominate

the finale, but it is

gradually overcome as Mahler

works towards a supremely

confident D major conclusion

- a triumph of the creative

will which, in this most

remarkable of first

symphonies, gives musical

shape to the experiences

which lie at the heart of

all Mahler`s music:

nostalgia for an ideal

pastoral simplicity or for

the innocence of childhood,

a morbidly sensitive

awareness of the remoteness

and fragility of that

innocence, and the turmoil

of a passionately individual

sensibility yearning for a

self-transcending union with

the natural world.

Andrew

Huth

|

|