|

|

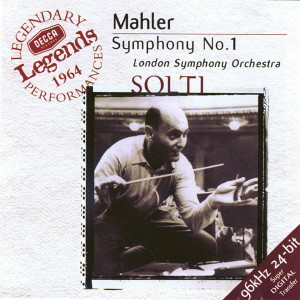

1 LP -

SXL 6113 - (p) 1964

|

|

| 1 CD -

458 622-2 - (c) 2001 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony No. 1 in

D Major

|

|

53' 51" |

|

- Langsam,

Schleppend, Wie Ein Naturlaut

|

15' 35" |

|

|

| - Kräftig Bewegt,

Doch Nicht Zu Schnell |

6' 55" |

|

|

| - Feierlich Und

Gemessen, Ohne Zu Schleppen |

10' 59" |

|

|

| -

Stürmisch Bewegt |

20' 22" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| London

Symphony Orchestra |

|

| Georg

SOLTI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kingsway

Hall, London (Inghilterra) -

gennaio/febbraio 1964 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

John

Culshaw |

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

James

Lock |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Decca

ffss | SXL 6113 (stereo) - LXT

6113 (mono) | (1 LP) | durata 53'

51" | (p) 1964 | Analogico

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Decca

"Legends" | 458 622-2 | (1 CD) |

durata 54' 01" | (c) 2001 | ADD

(96kHz 24-bit) |

|

|

Note |

|

(c) 1964,

The Decca Record Company

Limited, London

|

|

|

|

|

|

All that

apparently survives of

Mahler's juvenilia, apart

from fragmentary sketches,

is a complete opening

movement of a Piano Quartet

in A minor (wich was first

performed of the WBAI radio

station of New York in 1961)

and three complete songs

with piano - Im Lenz,

Winterlied and Maitanz

im Grünen (wich remain

in private hands, and still

await performance). There is

also a discarded first part

of the cantata Das

klagende Lied (the

first to be composed of

Mahler's published

compositions); this was

first performed on the BRNO

Radio in 1934. But no trace

has been discovered of any

early attempt by Mahler at

symphonic composition.

Yet it seems

certain that Mahler's first

published symphony - No. 1

in D - cannot have been the

first that he composed.

Memories have survived of a

symphony being rehearsed by

the students orchestra of

the Vienna Conservatoire,

while Mahler himself was

still a student there; of

three movements of a

youthful Symphony in A minor

(the finale was apparently

complete in the young

composer's head, but was

never committed to paper);

of an early "Nordic

Symphony"; and of 'two other

symphonies'. It was long

assumed that these and any

other symphonic products of

Mahler's teens in the

eighteen-seventies were

destroyed by him; but there

is reason to believe that

some of them, at least,

survived his death in 1911.

In 1938, the distinguished

Mahler-biographer Paul

Stefan, who had known the

composer, wrote an article

for the magazine Musical

America (issue of

April 10). In this he stated

that the great conductor and

Mahler-protegé Willem

Mengelberg had told him that

he had discovered the

manuscripts of 'four

complete symphonies of

Gustav Mahler's youth' in

the archives of the Weber

family in Dresden (Mahler

was on intimate terms with

the Webers during the years

1886-88); and that he had

actually played them over on

the piano with the composer

Max von Schillings during an

all-night session. Stefan

described all this as having

happened 'some time ago' -

it must have been before

1933, the year in which Von

Schillings died - but

nothing further has been

heard of these symphonies.

Stefan died in 1943 and

Mengelberg in 1951 - both

before the sudden

re-awakening of interest in

Mahler in the 'fifties - and

recent searching has so far

failed to reveal the

whereabouts of the

manuscripts in a much -

changed post-war Germany. It

may be that they were

destryed by the then

Baroness von Weber (Who has

also since died), as

according to Stefan she had

promised Mahler to prevent

them from ever being

performed.

The Mahler-enthusiast can

only hope against hope that

these scores will eventually

come to light. Although they

would no doubt be too

immature to enter the

repertoire, they would

nevertheless illuminate the,

at present, obscure path

traversed by the young

Mahler's musical

imagination, on its way

towards the fantastically

original 'Symphony No. 1 in

D' of which he conducted the

stormy première in Budapest

in 1889. For fantastically

original the work is, a fact

we should not forget now

that it is becoming such a

familiar part of our musical

experience.

Mahler's youth ful scores

might reveal, in the first

place, the steps by which he

came to score for such a

large orchestra - for this

seems to have been an

entirely original departure

on his part. Richard

Strauss, in the first

masterpiece Don Juan

(first performed, also under

its composer, just nine days

before Mahler's First

Symphony), was for the time

being quite happy with the

usual triple woodwind, four

horns, three trumpets, three

trombones and bass tuba.

Bruckner, in his Seventh

Symphony of four years

earlier, had admittedly

begun to call for the extra

four horns doubling tenor

tubas which Wagner had

demanded for The Ring;

but he had otherwise

remained content with normal

forces, even settling for

the modest double

woodwind of earlier

tradition. It seems to have

been Mahler who first used

practically the full Ring

orchestra of Wagner for a

symphonic work - quadruple

woodwind, eight

horns (but not doubling

tenor tabas, as with Wagner

and Bruckner), four

trumpets, Three trombones

and bass tuba - as well as

asking for a second timpani

player. He did so, of

course, not to achieve the

extra solemnity of Bruckner,

or the extra sumptuousness

of the later Strauss, but to

produce that sharply-etched

clarity - shrill woodwind,

whooping horns, biting brass

- which is the essence of

his orchestral style.

From Mahler's student

symphonies we might also

expect to trace the origins

of the startling stylistic

innovations which he brought

into the symphony. The

sudden unheard-of appearance

of a bird-call in the slow

introduction, for example

(that of the cuckoo), or the

unprecedented use of

'pop-music' elements: the

café-music schmalz

of the Scherzo's Trio, the zigeuner

tear-jerking and vulgarity

which intrude into the

Funeral March - not to

mention the simple

writing-out of the familiar

round on 'Frère Jacques' (or

rather on its German

minor-key equivalent,

'Bruder Martin'), and the

scoring of the result in the

most macabre colours, as the

main basis of the Funeral

March itself.

Even more, from a study of

those vanished scores, we

might be able to watch the

growth of the formidable

structural grasp which

enabled Mahler to integrate

such a mass of heterogeneous

elements into a symphonic

whole - and particularly his

power to set two violenty

contrasted tonalities at

each other's throats without

bursting the form apart at

the seams. The wildly

desparing F minor music

which breaks into the D

major pastoral geniality of

the First Symphony's opening

movement, and which takes

complete charge of the first

half of its eventually

triumphant D major finale,

presents an individual type

of schizophrenic

key-conflict which is only

contained and eventually

resolved by the sureness of

the unusually far-flung

structure. Such phenomenal

architectural power in a

first symphony argues a long

and arduous apprenticeship,

which may well have needed

at least four student works

to complete.

Deryck

Cooke

|

|