|

Several of

Mahler’s symphonies embody a

struggle with some spiritual

problem which is eventually

resolved in the finale. In

the Second, which he

completed in 1894 at the age

of thirty-four, the problem

is that of finding some

assurance in the face of

human mortality; and the

resolution is a

reaffirmation of the

Christian belief in

resturection and

immortality. This ‘meaning’

is conveyed clearly by the

symphony itself; but Mahler

ratified it in a verbal

‘programme’ which he drew up

for the work in 1896, a year

after its first performance,

in Berlin, at the request of

a young composer and

journalist, Max Maschalk,

who was one of his earliest

admirers.

At first, he

was unwilling to satisfy the

young man's curiosity,

insisting that the symphony

spoke for itself. He wrote

to Marschalk:

‘I should

regard my work as having

completely failed, if I

found it necessary to

give people like

yourself, even an

indication as to its

mood-sequence. In my

conception of the work,

I was in no way

concerned with the

detailed setting forth

of an event, but much

rather of a feeling. The

conceptual basis of the

work is spoken out

clearly in the words of

the final chorus, and

the sudden emergence of

the contralto solo [the

fourth movement] throws

an illuminating light on

the earlier movements’.

After several

protests, however, Mahler

consented to put into words

the idea behind the

symphony. He wrote as

follows:

‘I have

named the first movement

‘Totenfeier’ [Funeral

Rites, or Obsequies],

and if you want to know,

it is the hero of my D

major symphony [No.1]

whom I bear to the grave

there, and whose life I

catch up, from a higher

standpoint, in a pure

mirror. At the same time

there is the great

question: ‘Why did you

live? Why did you

suffer? Is it all

nothing but a huge,

terrible joke?' We must

answer these questions

in some way, if we want

to go on living -

indeed, if we are to go

on dying! He into whose

life this call has once

sounded must give an

answer; and this answer

I give in the final

movement.

The second

and third movements are

conceived as an

interlude. The second is

a memory - a shaft of

sunlight from out of the

life of this hero, It

has surely happened to

you, that you have

followed a loved one to

the grave, and then

perhaps, on the way

back, there suddenly

arose the image of a

long-dead hour of

happiness, which now

enters your soul like a

sunbeam that nothing can

obscure - you could

almost forget what has

just happened. That is

the second movement.

But when

you awake nom this

wistful dream, and have

to retum, into the

confusion of life, it

can easily happen that

this ever-moving,

never-resting,

never-comprehensible

bustle of existence

becomes horrible to you,

like the swaying of

dancing figures in a

brightly-lit ball-room,

into which you look from

the dark night outside -

and from such a great

distance that you can no

longer hear the music.

Life strikes you as

meaningless, a frightful

ghost, from which you

perhaps start away with

a cry of disgust. This

is the third movement;

what follows is surely

clear to you.’

Five years

later, for another Berlin

performance, Mahler drew up

another programme, this time

for public consumption. His

explanation of the first

three movements was along

exactly the same lines as

before, but it was now

followed by a commentary on

the rest of the symphony:

‘Fourth

Movement: the morning

voice of ingenuous faith

strikes on our ears.

Fifth

Movement: we are

confronted once more

with terrifying

questions. A voice is

heard crying aloud: ‘The

end of all living things

is come - the Last

Judgment is at hand’

.....

The earth quakes, the

graves burst open, the

dead arise and stream on

in endless procession.

The great and the little

ones of the earth -

kings and beggars,

righteous and godless -

all press on; the cry

for mercy and

forgiveness strikes

fearfully on our ears.

The wailing rises higher

- our senses desert us,

consciousness fails at

the approach of the

eternal spirit. The last

trumpet is heard - the

trumpets of the

Apocalypse ring out; in

the eerie silence which

follows, we can just

catch the distant,

barely audible song of a

nightingale, a last

tremulous echo of

earthly life. A chorus

of saints and heavenly

beings softlly breuks

forth: "Thou shalt

arise, surely thou shalt

arise’. Then appears the

glory of God: a wondrous

soft light penetrates us

to the heart - all is

holy calm.

And behold,

it is no judgment; there

are no sinners, no just.

None is great, none small.

There is no punishment and

no reward. An overwhelming

love illuminates our

being. We know and are.'

On the very

day of the performance,

however, Mahler had a

revulsion back to his

earlier distrust of

programmes. He wrote to his

wife:

‘I only

drew up the programme as

a crutch for a cripple

(you know who I mean).

It can give only a

superficial indication,

all that any programme

can do for a musical

work ..... In fact, as

religious doctrines do,

it leads directly to a

flattening and

coarsening, and in the

long run to such

distortion that the work

..... is utterly

unrecognisable.’

In view of

Mahler’s ambivalent attitude

towards his programme, what

value can it have for us

today? Some modern musicians

would advise us to ignore it

altogether - quoting

Mahler’s own disparagement

of it as the best reason -

and to experience the

symphony purely as ‘absolute

music’, as so much

fascinating melody, harmony,

rhythm, orchestration, and

form. But this seems

impossible, since the work

itself contains its own

programme: the last two

movements have explicit

verbal texts, while the

wordless first movement

mounts an assault on our

emotions which we can hardly

ignore. In any case, Mahler

himself would not have

agreed with this point of

view. In his letter to

Marschalk outlining the

programme, he wrote:

‘We find

ourselves faced with the

important question how,

and indeed why music

should be interpreted in

words at all ..... As

long as my experience

can be summed up in

words, I write no music

about it; my need to

express myself musically

- symphonically - begins

at the point where the

dark feelings hold sway,

at the door which leads

into the ‘other world’ -

the world in which

things are no longer

separated by space and

time.'

Clearly then,

Mahler expected us to

experience the symphony, not

at all as absolute music,

but as the musical

expression of feelings too

mysterious and deepseated to

be described in words, even

his own, without being

distorted. But this would

demand an ideal listener,

who could so immediately

respond to the feelings in

the music as to have no need

of reflection or

clarification. Many a

music-lover likes to analyse

the feelings that music

awakens in him; moreover,

those who are puzzled by the

work may need some

indication as to the general

area of feeling the

music is concerned with.

What we should do, perhaps,

is neither reject Mahler's

programme, nor take it

literally, but try to

penetrate to its valid

psychological core, shearing

away all inessentials.

To begin with,

the later addition,

concerning the last two

movements, is strictly

redundant. In the fourth

movement, both the folk-poem

and its hymn-like setting

proclaim explicitly their

‘ingenuous faith’; and the

vivid tone-painting in the

finale portrays unmistakably

the image of the Day of

Judgment, while the final

chorale-like setting of

Klopstock’s ‘Resurrection

Ode' (with even more

explicit verses added by

Mahler himself) also speaks

for itself. (Mahler had

actually stressed all this

in his letter to Marschalk,

as we have seen.) And the

final paragraph, about there

being ‘no judgment’, is not

only redundant, but

irrelevant: Mahler was no

doubt carried away by

writing about the concept of

an after-life into adding a

purely doctrinal view, which

he happened to hold at the

time, but which has no

bearing on the symphony at

all. Indeed, it may well

have been his later

realisation of this which

caused his revulsion from

the whole programme - a

conjecture which finds

support in an amusing

unecdotc in his wife’s book:

‘There was

a beautiful old lady of

hysterical tendencies,

who ..... when Mahler

was in Russia .....

summoned him and.told

him that she felt her

death to be near, and

would he enlighten her

about the other world,

as he had said so much

about it in his Second

Symphony. He was not so

well informed about it

as she supposed, and he

was made to feel very

distinctly, when he took

his leave, that she was

displeased with him.’

How should

Mahler have known anything

about the nature of the

after-life, or even whether

there was such a thing? In

his last two movements he

had simply expressed, in

symbolic terms, his own faith

- in God, resurrection, and

eternal life; and they need

no programme, nor any

doctrinal gloss.

The

‘resurrection’ finale links

back, thematically and

emotionally, with the large

opening movement; and

according to Mahler’s

programme, it ‘answers the

questions’ of this movement.

But it is rather the

questions of Mahler’s programme

(Why did you live? Why did

you suffer? Is it all

nothing but a huge, terrible

joke?) which are answered by

part of the text he

himself added to Klopstock’s

Ode for his finale (O

believe, thou wert not born

in vain, hast not lived in

vain, suffered in vain).

Obviously, a purely

orchestral movement cannot

ask questions, because music

by itself is incapable of

doing so. If Mahler had not

drawn up his programme, we

should have had no idea that

it was intended to ask

questions at all.

It is here

that we have to look beyond

Mahler’s loose phraseology

to the psychological reality

behind it. The first

movement has the rhythm and

character of a funeral

march, but a quicker tempo;

and whereas the normal

funeral march is a dignified

expression of grief,

Mahler’s movement is full of

anger, revolt, and wild

despair. It clearly

expresses the state of mind

of one who feels a sense of

outrage at the apparent

omnipotence of death, and

can find no ultimate

significance in human life

in the face of it - a state

of mind which implies the

‘questions’ in the

programme.

The same approach is

necessary with Mahler’s

curious phrase ‘it is the

hero of my D major symphony

whom I bear to the grave

there’. A symphony cannot

have a hero, and its

composer cannot bear him to

the grave in the next

symphony. But

programme-symphonies of this

kind deal in universal

statements about mortal

humanity, and the ‘hero’ of

a Mahler symphony is simply

Mahler’s projection in his

own mind of the person whom

these statements concern:

Everyman, or at least every

man in the same predicament

as Mahler. Mahler’s phrase

was only a symbolic way of

saying that in the First

Symphony the universal

implications of the funeral

march (the third movement in

this case) are eventually

swept aside and ignored in

the finale through an

affirmation of youthful

vitality and confidence; but

in the Second Symphony these

implications are ‘caught up

from a higher standpoint’ -

i.e., confronted on the

metaphysical plane and

resolved by an act of

religious faith.

The

programme’s description of

the second and third

movements confronts us with

visual images, but again we

must penetrate to their

underlying psychological

meaning. The images of the

memory at the graveside and

the far-off inaudible

ballroom music are poetic

analogies indicating that

the first movement’s vision

of death’s omnipotence is

followed by a two-movement

interlude concerned with

life - its happiness and its

bitterness. For these

Mahler, as so often, used

the Austrian country waltz,

the Ländler, to symbolise

the ‘dance of life’. But the

first movement’s

overpowering character has

the effect of shrinking the

vision of life’s happiness

here to a small space, and

to a subdued and fragile

thing. The second movement

is a short slow Ländler,

basically wistful in mood

and eventually overshadowed

by an intrusion of the first

movement’s angry atmosphere

(in the second statement of

its trio-section); this

reduces the final statement

of the wistful Ländler

section to a disembodied

ghost of itself (though it

later regains its

substance).

In the third

movement, the scherzo,

Mahler uses the quicker type

of Ländler for his vision of

life’s bitterness - total

bitterness, according to his

programme, though most

admirers of the symphony

sense other feelings there

as well - genial vitality,

humour and longing. The

relentless twisting and

twining of the main material

certainly has something

sinister about it, but

something comical as well;

in fact Mahler lifted it

bodily from his amusing song

‘St. Anthony of Padua’s

Sermon to the Fishes’, where

he had conceived it to

portray the aimless

gyrations of the fish, as

they listened to the sermon

but swam away as sinful and

greedy as before. And in the

two trio-sections there is

some exuberant popular

dance-music and a haimtingly

nostalgic passage for four

trumpets in close harmony.

Yet the

general effect of the

movement, in the context of

the whole symphony, is

without doubt that of a

complacently persistent

busy-ness, on a plane of

easy pleasure, which does at

times take on a macabre

shadowiness: the ‘Dance of

Life’ appears here as a

purely mechanical and

sometimes insubstantial

activity, with no high aim

and purpose. Whether it

appears ‘horrible’, as

Mahler believed it did, may

be a matter of personal

reaction; but undeniably,

the sense of an apparently

unstoppable nattering and

nagging does become so

strong in the end as to

motivate the extraordinary

revulsion which is the

climax of the movement - the

great outburst which Mahler

described as ‘a cry of

disgust’. And the opening of

the hymn-like movement for

contralto solo, which

follows this movement

without a break, certainly

comes as a welcome relief

and an elevation to a higher

plane.

So the

‘programme’ of the symphony

resolves itself into a

symbolic description of a

psychological mood-sequence:

a sense of outrage at the

omnipotence of death, a

haunting awareness of the

fragility of life’s

happiness, and a feeling of

disgust at the mechanical

and aimless triviality of

everyday life, followed by a

turning away to faith in God

and belief in resurrection

and etemal life.

Even so, we

are still left with a

nagging question. The ‘call’

which ‘sounded through’

Mahler’s life - the

challenge to find some

significance in a life which

is doomed to extinction - is

one familiar to most of us,

and we can find no

difficulty in responding to

the feelings expressed in

the first three movements.

But for the many of us who

cannot answer this challenge

by invoking the Christian

belief in immortality, what

significance can there be in

the culmination of the

symphony - the part which

presents the ostensible

‘message’ of the work?

Strangely

enough, it does have great

significance for us, since a

hearing of it comes as a

kind of tremendous emotional

experience. Yet the reason

is clear. Music cannot

express intellectual

concepts, but only feelings;

and what we all respond to

is the feelings of faith and

inspiration in the music,

whether or not we are

convinced by the concepts in

the text which were the

object of these feelings.

Mahler’s affirmations are

ultimately of faith and

inspiration in life itself,

whether they arose, as in

the second, third, and

eighth symphonies, from the

religious beliefs he held at

the time, or, as in The

Song of the Earth and

the unfinished tenth, from

his realistic coming to

terms with mortality when

his religious beliefs failed

him. The ‘Resurrection

Symphony’ raises us, not

into another world, but on

to the plane of spiritual

conflict and achievement

where life alone has value

and significance.

From the musical point of

view, the separate movements

of the symphony have an

immediate formal clarity and

impact which makes analysis

unnecessary. But it may be

helpful to point out the

symphony’s broader formal

cohesion - the thematic

interconnections between the

earlier movements and the

finale.

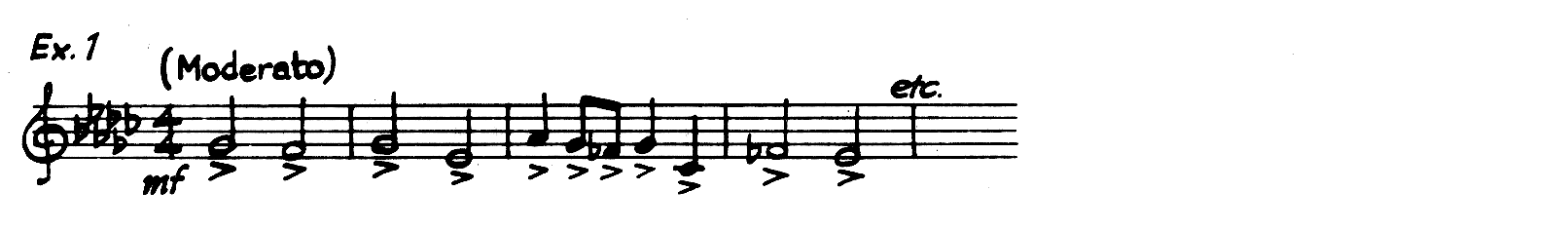

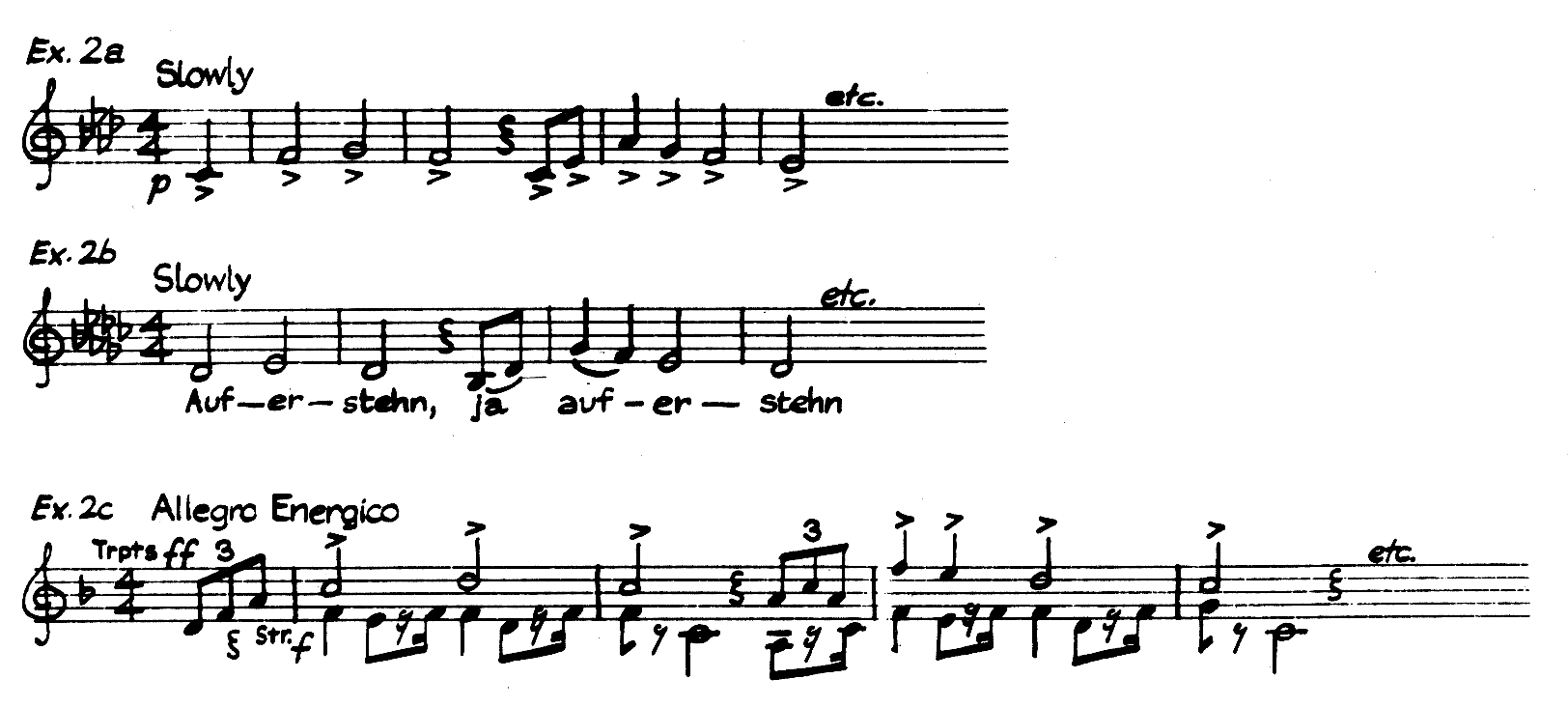

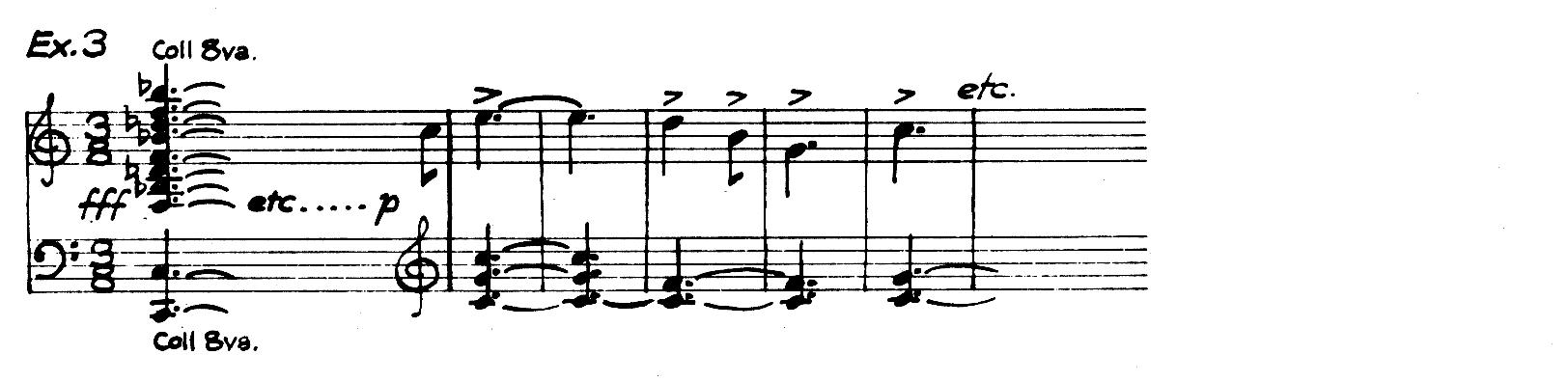

In the

development section of the

first movement, Mahler

introduces two new themes.

The second of these is a

kind of chorale-melody,

given out by the horns,

which begins with the first

four notes of the Dies

Irae, but continues in

more confident mood (Ex. 1).

The last idea which the

finale takes up from the

earlier part of the symphony

is a passage from the fourth

movement; and here there is

a verbal as well as a

musical connection. The

melodic line to which the

contralto sings ‘I am from

God, and will return to God’

(Ex. 4a) is developed in

much faster tempo by both

soloists in the finale, to

the words ‘With wings which

I have won me, in love's

fierce striving, I shall

soar upwards to the light to

which no eye has penetrated’

(Ex. 4b).

Deryck

Cooke

|