|

|

2 LP's

- SET 469-70 - (p) 1970

|

|

| 2 CD's -

416 674-2 - (c) 1985 |

|

| 1 CD -

425 040-2 - (c) 1992 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 6 in A Minor |

|

76' 49" |

|

Long Playing 1 -

SET.469

|

|

49' 16"

|

|

| - 1. Allegro

energico, ma non troppo |

21' 03" |

|

|

| - 2. Scherzo.

Wuchtig |

12' 33" |

|

|

-

3. Andante moderato

|

15' 34" |

|

|

Long Playing 2 -

SET.470

|

|

43' 34"

|

|

| -

4. Finale: Allegro moderato |

27' 28" |

|

|

| Lieder

eines fahrenden Gesellen |

|

15' 58" |

|

| -

a) Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht |

4' 01" |

|

|

| -

b) Ging heut' morgen über's Feld |

3' 50" |

|

|

| -

c) Ich hab ein glühend Messer |

3' 00" |

|

|

| -

d) Die zwei blauen Augen |

5' 07" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yvonne Minton,

contarlto (a-d)

|

|

| Chicago Symphony

Orchestra |

|

| Georg Solti,

conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Medinah

Temple, Chicago (USA) -

marzo/aprile 1970 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

David

Harvey |

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

Gordon

Parry

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Decca

ffss | SET 469-70 (stereo) | (2

LP's) | durata 49' 16" - 43' 34" |

(p) 1970 | Analogico

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Decca

| 416 674-2 | (2 CD's) | durata

49'16" - 43' 34" | (c) 1985 | ADD

(ADRM)

Decca "Ovation" | 425 040-2 | (1

CD) | durata 65' 53" | (c) 1992 |

ADD (ADRM) (only Symphony)

|

|

|

Note |

|

The

Decca Record Company Limited,

London

|

|

|

|

|

GEORG

SOLTI & THE CHICAGO

SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

Fifteen years

were destined to separate

Georg Solti’s debut as a

guest leader of the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra - at

summer concerts of the

Ravinia Festival - and his

first Orchestra hall

appearance, downtown, as

music director in the autumn

of 1969 The first encounter,

however, in 1954, was

instantaneously productive

of a mutual respect and

rapport that deepened with

each subsequent interim

meeting. No matter who was

resident conductor in

Chicago, or what traditions

variously prevailed whenever

Solti would return as a

guest, the orchestra each

time became his ally-as such

the mirror of a singular

aesthetic temperament in our

time. The precision that

Solti has always demanded in

musical performance (as an

essential for musical

expression) has been his to

command in whatever

capacity, under whatever

circumstances, at whatever

time.

With his

appointment as music

director, thereby continuing

an artistic heritage

hand-fashioned by Artur

Rodzinski (1947-48) and

Fritz Reiner (1953-63), the

alliance of conductor and

orchestra has produced a

synchronous artistry without

parallel in Chicago’s

musical history. By no means

is this said to

underestimate the

achievements of Solti’s

predecessors, without the

finest of them he would not

now have the superlative

assembly at his summons. But

none before him in memory -

and some before him

possessed awesome powers -

could quite persuade the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

to give so eloquently of

themselves at the same time

as they sustained such a

high level of discipline.

Early on this interaction of

a great conductor and a

great orchestra surpassed

such essentially irrelevant

concerns as love for one

another.

Respect and

rapport are the rudiments of

Georg Solti’s astounding

achievement to date in

Chicago, as documented on

these discs for the first

(but surely not for the

last) time. To some persons,

as the years lengthened into

a decade, and beyond, it may

have seemed that the

eventual union of Georg

Solti and the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra was not

meant to be. But to others

of us, the long wait served

instead to whet the appetite

further for what promised,

on each visit, to be an

artistic inevitability - and

has indeed proved to be,

altogether beyond

expectations.

Roger

Dettmer

Music and

Theatre Critic Chicago

Today

notes by

DERYCK COOKE

Mahler

conducted the première of

his Sixth Symphony at the

German Music Festival held

in Essen in 1906, where it

proved to be the most

talked-of new work, together

with that very different

masterpiece, Delius’s Sea-Drift.

It made a great impression

on Schoenberg, who praised

its subtle melodic structure

and bold harmonic style, and

a greater one on Berg, who

called it ‘the only Sixth,

despite Beethoven’s

Pastoral’.

There is indeed something

uniquely overwhelming about

this particular symphony of

Mahler, which may be due to

its extremely personal

inspiration. His wife, Alma,

writing of the ‘composing

holidays’ they spent with

their two little daughters

in the summers of 1904 and

1905, said:

After he

had drafted the first

movement, he came down

from the wood to tell me

he had tried to express

me in a theme. ‘Whether

I’ve succeeded, I don’t

know; but you’ll have to

put up with it’.

This is

the great soaring theme

of the first movement of

the Sixth Symphony. In

the third movement [now

the second-see below] he

represented the

unrhythmical games of

the two little children,

tottering in zigzags

over the sand.

Ominously, the childish

voices became more and

more tragic, and at the

end died out in a

whimper. In the last

movement he described

himself and his downfall

or, as he later said,

his hero: ‘It is the

hero, on whom fall three

blows of fate, the last

of which fells him as a

tree is felled’. Those

were his words.

Not one of

his works came as

directly from his inmost

heart as this. We both

wept that day. The music

and what it foretold

touched us so deeply...

Again, when

Mahler first heard the

music, while preparing the

Essen première, he was quite

overcome. The experience,

moreover, was heightened by

one of those curious

coincidences that cropped up

throughout his life:

None of his

works moved him so deeply

at its first hearing as

this. [In fact, he never

heard The Song of the

Earth, the Ninth, or

of course the Tenth.] We

came to the last

rehearsals, the

dress-rehearsal-to the

last movement with its

three blows of fate. When

it was over, Mahler walked

up and down in the

artists’ room, sobbing,

wringing his hands, unable

to control himself. Fried,

Gabrilovitch, Buths and I

stood transfixed, not

daring to look at one

another. Suddenly Strauss

came noisily in, noticing

nothing. ‘I say, Mahler,

you’ve got to conduct some

dead march or other

tomorrow, before the

Sixth-their mayor has died

on them. So vulgar, that

sort of thing-But what’s

the matter? What’s up with

you? But -’ and he went

out as noisily as he had

come in, quite unmoved,

leaving us petrified...

Today we do

not believe that composers

‘foretell’ their own fate in

their music. Nevertheless, a

year later, three blows did

fall on Mahler, and the last

one ‘felled’ him. In the

spring his resignation was

demanded at the Vienna

Upera; in July, his daughter

Anna died, at the age of

four; and a few days later,

a doctor diagnosed Mahler’s

own fatal heart disease.

Mahler was of course - like

Webster in T. S. Eliot’s

poem - ‘much possessed by

death’, and he was

superstitious about it: he

later went so far as to

delete the ‘prophetic’ final

hammer-blow in the

symphony’s finale.

All this explains why Mahler

called the Sixth his Tragic

Symphony. It might seem

strange for him to give this

title to one particular

work, when he is so widely

regarded as altogether a

‘tragic’ composer. Yet after

all, six of his eleven

symphonic works - Nos. I, 2,

3, 5, 7 and 8 - culminate in

a blaze of triumph in the

major; another - No. 4 -

dies away in blissful

serenity, also in the major;

and three others - The

Song of the Earth, No.

9 and No. 10 - fade out in

resigned reconciliation,

once more in the major. The

Sixth alone offers no

escape, ending starkly in

the minor mode - that

essential tragic symbol of

the nineteenth-century

composer.

The work was, in fact, the

first genuine ‘tragic

symphony’ to be written. The

romantic concept of the

heroic human struggle

against fate, derived from

Beethoven’s Fifth, is its

basis - but Beethoven’s

struggle has a triumphant

outcome, as have those in

several of Mahler’s own

symphonies. The purely

tragic concept was first

hinted at in Brahms’s

Fourth, which ends sternly

in the minor; but the fierce

vitality of the conclusion

precludes any idea of a

tragic catastrophe.

Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique

certainly ends in utter

darkness ; but its mood of

breast-beating despair is

far removed from the

objective universality of

tragedy. In Mahler’s Sixth,

however, a truly tragic

catastrophe, akin to those

in Greek and Shakespearean

drama, is presented with

stark objectivity. And woven

into it is a Hardy-like

backcloth of nature, of

mountain heights, far above

human turmoil. This acts as

a refuge in the slow

movement, but in the first

movement and finale as a

purely elemental world,

indifferent to human

suffering.

The work’s unique character

has been briefly and

powerfully summed up by

Bruno Walter:

...the

Sixth is bleakly

pessimistic: it reeks of

the bitter cup of life.

In contrast with the

Fifth, it says ‘No’,

above all in its last

movement, where

something resembling the

inexorable strife of

‘all against all’ is

translated into music.

‘Existence is a burden;

death is desirable and

life hateful’ might be

its motto ... The

mounting tension and

climaxes of the last

movement resemble, in

their grim power, the

mountainous waves of a

sea that will overwhelm

and destroy the ship;

the work ends in

hopelessness and the

dark night of the soul.

‘Non placet’ is his

verdict on this world;

the ‘other world’ is not

glimpsed for a moment.

Walter views

the Symphony as a personal

statement, and, as we have

seen, its inspiration was

extremely personal;

moreover, the music, as

always with Mahler, is as

personal as music can be.

How then can the work

possess the objective

universality of tragedy?

Simply in that here, as

nowhere else in Mahler’s

symphonies, his personal

expression of dread and doom

and disaster is subjected to

an iron classical control,

in two separate ways. First,

although Mahler’s formal

command is always greater

than is generally realised,

only in the Sixth did he

follow the traditional

classical layout. Despite

its characteristically vast

time-scale and enormous

orchestra, the Symphony has

neither vocal elements, nor

direct quotations from

songs, nor bird-calls, nor

bugle-signals, nor passages

in the popular style, nor

any explicit programme. And

not only does it consist of

the traditional four

movements, but three of them

- the opening

sonata-movement with

repeated exposition, the

scherzo with trio, and the

finale - are all in the same

key of A minor.

But all this in itself could

not have guaranteed

classical control. The

second, complementary means

to this end was the

objectifying of the thematic

material itself, most of

which (as so often with

Bruckner) looks back beyond

romantic lyricism to the

motivic methods of the

classical symphony: not to

the actual classical style

- the themes are far too

emotionally charged - but to

the classical clarity and

concision. These elements

are of course partly present

in Mahler’s other

symphonies; and there are

still exceptions here, such

as the opening movement’s

expansive lyrical second

subject (the ‘Alma’ theme -

Ex. 6 - supposed to portray

his wife), the song-like

main melody of the Andante

moderato, and certain

almost impressionistic

passages in the finale’s

introduction. Nevertheless,

the classical side of

Mahler’s complex musical

personality is concentrated

into this work far more

potently than into any of

his others, and this

notwithstanding the length

at which the material is

developed, especially in the

finale, which is practically

a symphony in itself.

Before turning to the music,

one should mention the

problem of the order of the

two inner movements. The

symphony was first published

with the scherzo second and

the slow movement third; but

Mahler switched them round

for a second publication.

The symphony came down in

this latter form after his

death, and the rare

performances of it always

followed this order. But it

has since transpired that,

shortly before his death, he

reverted to the original

order, as well as revising

the orchestration (this was

when he removed the finale’s

third hammer-blow, as

mentioned above). This final

version was published by the

International Mahler Society

of Vienna in 1963, and has

been used by Georg Solti for

the present recording.

In keeping with its

classical character, the

Sixth is the only Mahler

symphony which does not rely

on cyclic form - the

Lisztian method of

transferring themes from one

movement to another, and

especially from one or more

movements to the finale -

though it does have a brief

‘tragic motto’ of two chords

(Ex. 4), which occurs in the

opening movement, scherzo,

and finale. In consequence,

the work is closely unified

by motivic and rhythmic

interrelationships between

the themes of each movement,

and between the movements

themselves.

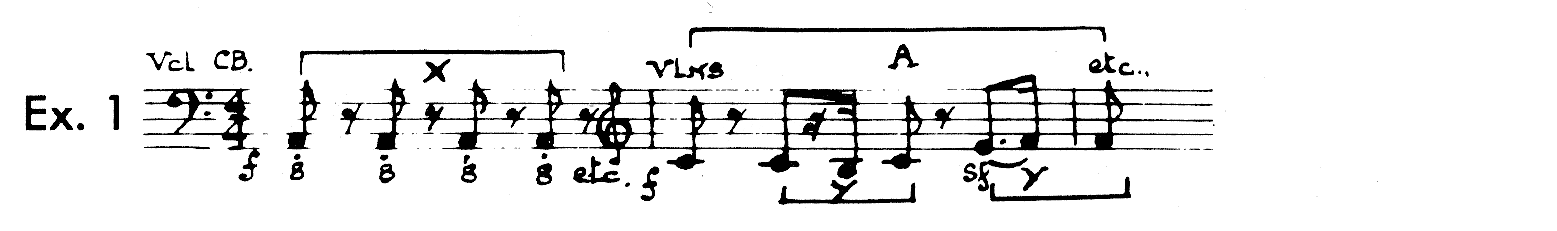

The opening Allegro

energico, ma non troppo,

a heavy march-movement, has

a brief introduction (Ex.

1), which begins with a

tramping repetition of the

note A (marked X), then sets

the basic rhythm of the

whole work (marked Y), and

at the same time introduces

a motive (marked A) which is

to be pervasive.

The first

subject continues with a

whole group ofideas, three

of which are also to

permeate the movement. The

first (Ex. 3a) derives from

the original motive A; the

second (Ex. 3b) is new, but

centres like everything else

on the rhythm Y; and the

third (Ex. 3c) derives from

the opening phrase B of the

first subject.

After a

powerful climax, the ‘tragic

motto’ of the Symphony

strikes in (Ex. 4) - a

brilliant A major triad for

trumpets, fading to a weak A

minor one on oboes, over a

heavy military rhythm

(including Y), plus a

snare-drum roll.

The

‘transition’ follows

immediately (Ex. 5) - a

quiet chorale-like theme for

woodwind, supported by quiet

memories of phrase B from

the first subject.

The theme does

not modulate to a new key,

but prepares to close in A

minor - whereupon the second

subject bursts in, in F

major (Ex. 6) - the

passionate ‘Alma’ theme,

supposed to be Mahler’s

musical portrait of his

wife. It too is shot through

with the rhythm Y, and also

incorporates the rhythm of

the second phrase (C) of the

first subject.

The development section

returns to the march-music,

even more grimly, varying

and transforming all the

foregoing material, with a

strikingly macabre version

of Ex. 3b, emphasised by

xylophone (this is the only

symphony in which Mahler

used the instrument). At one

point, there is a sudden pianissimo

visionary episode - in which

cowbells are heard, together

with ghostly references to

the chorale-theme, Ex. 5 -

suggesting the rarified

atmosphere of mountain

heights, far above the

turmoil. But the music

eventually resumes marching,

with a new confident version

of Ex. 3c, and soon leads to

the shortened

recapitulation. This opens

deceptively, with the first

subject resplendent in A

major, only to plunge back

immediately into A minor.

When it is over, the long

coda reverses the process:

beginning darkly in the

minor, with pianissimo

trombones referring back

ominously to phrase B of the

first subject, it eventually

culminates in a joyful,

brassy A major apotheosis of

the ‘Alma’ theme.

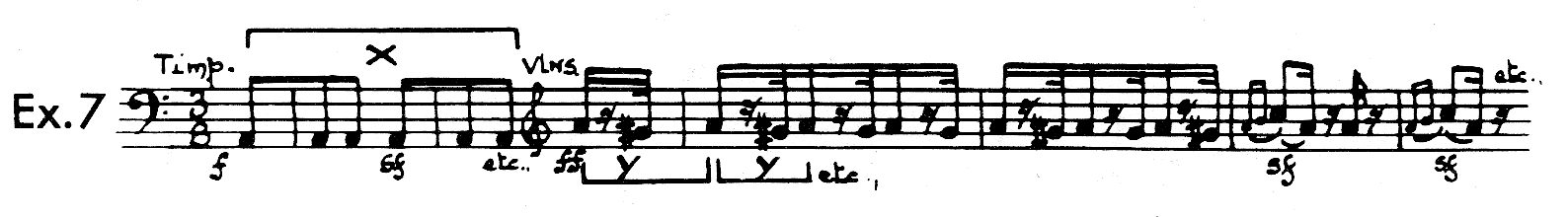

The close motivic unity

continues in the gruesome

comedy of the scherzo: its

three sections are widely

contrasted, but the last two

stem straight from motives

in the first. This first

section is a ferocious

stamping dance (Ex. 7). It

begins like the first

movement with heavy

repetitions of the note A in

the bass (marked X - cf. Ex.

1); it also looks back to

the opening movement’s first

subject, revolving around

the notes A and C (cf.

figure B in Ex. 2); and it

is saturated with the

rhythmic figure Y.

This will be

the starting point of the

third section, an eerie,

puppet-like, Hoffmannesque

episode (woodwind, muted

trumpets, strings struck

with the wood of the bow).

The other motive (Ex. 9) is

a forceful alternation of

bars of 3/8 and 4/8

(producing an effect of

7/8), which stems from the

basic repeated-note figure,

X.

The first section ends with

the symphony’s ‘tragic

motto’ (Ex. 4); the second

follows immediately; and

then the repeated A in the

bass (X) leads to the third,

which in turn leads back to

the first again, for a

varied repeat of the whole

three-section process. There

is a manifest sense of the

first and third sections

‘menacing’ the second one,

and after the third has come

back for the second time,

the character of the coda

seems inevitable: a forlorn

return and pathetic

disintegration of the second

section. Mrs. Mahler’s

phrase, ‘the childish voices

become more and more tragic,

and at the end die out in a

whimper’, is entirely

apposite.

The Andante moderato

is an idyllic interlude

which, reintroducing the

cowbells, suggests the peace

of mountain heights and

valleys (tinged with regret

and melancholy); not

surprisingly then, its key

is the remotest possible - E

flat major. It is built from

an expansive development of

two main ideas, which

alternate and intermingle.

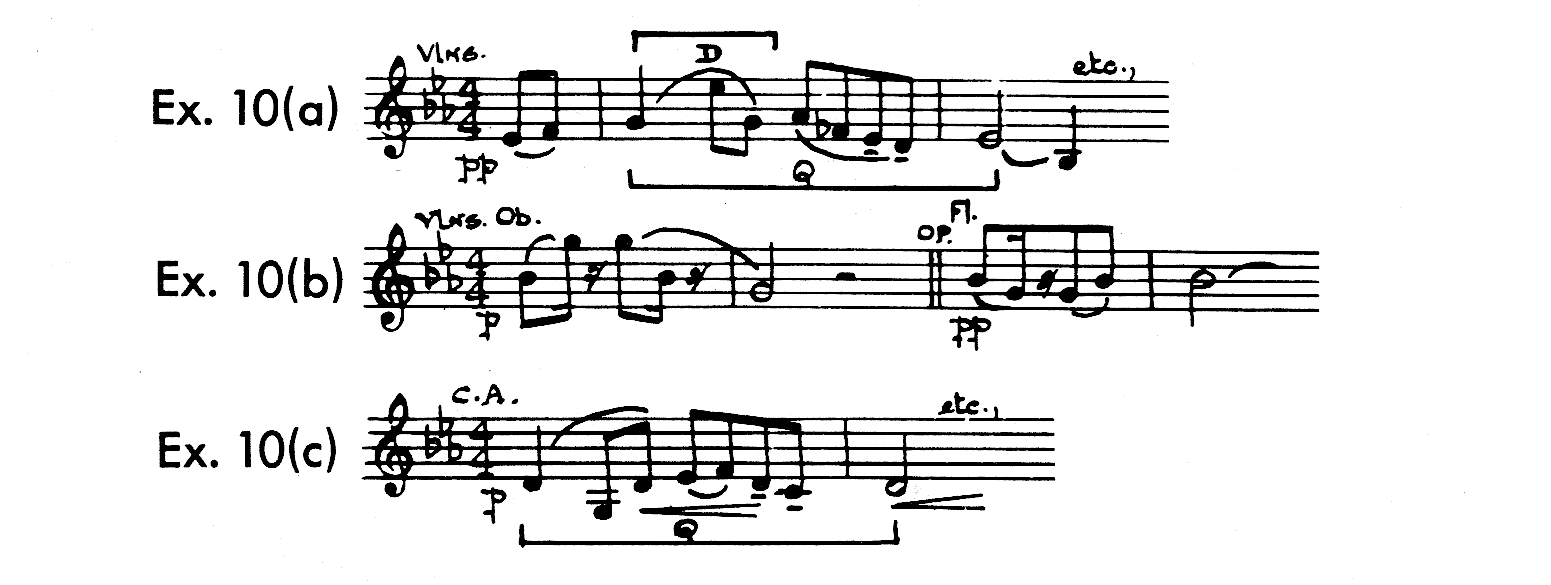

The first is the serene

string melody of the opening

(Ex. 10a) ; from the figure

marked D a rocking motive is

generated (Ex. 10b), which

will permeate the movement;

and from a murmuring of this

motive on flutes, the second

idea emerges, a haunting cor

anglais melody (Ex. 10c).

Although this movement

contains no motivitic

reference to the first two,

and no use of the ‘tragic

motto’, it is itself closely

unified by the rhythmic

identity between the opening

phrases of the two themes

(marked Q).

The theme

immediately switches to A

minor and repeats itself;

grinding against the ‘tragic

motto’; after which the tuba

gives out a lugubrious

phrase (Ex. 12), stemming

from the rising octave of

Ex. 11. It also incorporates

the rhythm Y, and is in fact

a free transformation of the

first movement’s first

subject (Ex. 2), via the

main theme of the first

section of the scherzo (Ex.

7).

This phrase is

answered by the arpeggio

figure from the scherzo

(figure Z in Ex. 8). Then,

out of further mists (the

cowbells appear again)

emerges a questing

horn-theme (Ex. 13), which

is already in mid-course

before its presence is felt;

and this too incorporates

the rhythm Y.

An

extraordinary fantasia-like

passage follows, bringing

premonitions of Schoenberg

and Stravinsky: it leads to

a dark C minor chorale-theme

for woodwind, in the depths

(Ex. 14).

This

culminates in the ‘tragic

motto’; but then the bass

woodwind introduce a more

vital idea (Ex. 15), also

incorporating the rhythm Y.

The first subject is a

driving march-theme

compounded of Exs. 12 and

15, which goes on to

incorporate most of the

ideas from the introduction.

At its first strong cadence,

it continues with the last

main idea - a ‘fate’ theme

given out by six horns in

unison (Ex. 16) ; this, as

can be seen, begins by

reconverting the rising

octave of Exs. 11 and 12

back to the falling octave

of the first movement (Ex.

2), and also picks up the

rhythm of the introduction’s

dark chorale (Ex. 14).

*

*

*

*

By the time that Mahler

wrote the Sixth, he had

stopped using his songs as

the basis of movements in

his symphonies - though the

(unquoted) continuation of

Ex. 13 above has a close

kinship with the main

thematic phrase of the last

of the Kindertotenlieder,

written about the same time.

The Lieder eines

fahrenden Gesellen

(Songs of a Wayfaring Lad)

take us back some twenty

years, to the time when he

was just beginning to be a

‘song-symphonist’, as the

misleading phrase goes. He

was twenty-four when he

completed the cycle, in

1884, and during the next

four years he composed his

First Symphony, drawing on

two of the songs for the

purpose. The second song, in

which the jilted lover,

having sung of his sorrows

in the first, sets out

across the countryside on a

bright sunny morning,

provided much of the

thematic material of the

symphony’s pastoral first

movement, the third song, in

which he sings of the

‘burning knife within his

bosom’, found no place in

the symphony, but the last,

in which he symbolically

embraces death by falling

asleep under a linden-tree,

provided the consolatory

trio-section of the

Symphony’s bitter Funeral

March. The point, in any

case, is that the songs are

embryonically symphonic:

Mahler was no

‘song-symphonist’, in fact,

but a symphonist and a

symphonic song-writer.

|

|