|

According to

the definitive numbering,

Mahler composed nine

symphonies, and the one on

this record is the last. But

if we include The Song

of the Earth

(subtitled ‘A Symphony for

Voices and Orchestra’) and

the full-length draft of the

Tenth, the complete tally,

as Mahler’s biographer

Richard Specht pointed out

as early as 1913, is eleven,

of which ‘No. 9’ is the last

but one. But in tact, this

total symphonic output

resolves itself into three

trilogies - early,

middle-period, and late -

separated from one another

by two single works. Specht

pointed out the first two:

to Mahler’s early period of

soaring philosophical

idealism belongs the first

trilogy, Nos. 1 to 3; then,

after the idyllic interlude

of No. 4, comes the stark,

realistic middle-period

trilogy, Nos. 5 to 7. And

finally, we may add, after

the colossal No. 8 - the

socalled ‘Symphony of a

Thousand’, which stands

apart-there is the dark

‘farewell’ trilogy of the

death-haunted last years. The

Song of the Earth, No.

9 and No. 10.

The reason why

this last-period trilogy is

so urgently concerned with

death is that in 1907, after

completing the ‘Symphony of

a Thousand’ as the titanic

affirmation of a man in the

prime of life, Mahler was

told by his doctor that he

was suffering from a fatal

heart-disease. He was in

fact to die only four years

later, at the age of fifty,

without having heard either

The Song of the Earth

or No. 9, and without even

having elaborated his

full-length draft of No. 10

into its final

full-orchestral form. No. 9,

completed in 1910, a year

before his death, received

its first performance in

1912, in Vienna, under Bruno

Walter.

The work has

for long been regarded as

Mahler’s despairing

swansong; but since we have

come to know the nature and

character of No. 10, we can

now understand No. 9 more

clearly as the central work

in the last-period trilogy.

Like its equivalents in the

two earlier trilogies - the

tormented death - and

resurrection No. 2, and the

stoic

death-without-resurrection

No.6 - it plunges into a

darkness which represents

the spiritual nadir of its

period; but in this final

trilogy, everything is on a

much more desperate plane

than before. The Ninth

Symphony marks Mahler’s

furthermost descent into the

hell of emptiness that

confronted him when he

received the death-sentence

from his doctor and found

his hard-sought faith too

insecure to exorcise the

spectre of a

swiftly-approaching

premature extinction. The

preceding Song of the

Earth, unutterably

poignant though it is,

evokes the shadow of death,

and utters a farewell to

life, in purely poetic

terms; the succeeding Tenth,

though it too plumbs the

depths, eventually rises

above the fear of death, and

the drama of leave-taking,

to a calm and transfigured

acceptance; but in the

Ninth, death is real and

omnipotent, and the farewell

is a heartbroken one. This

work is, in truth, Mahler’s

‘dark night of the soul’,

and it is all the more

moving in that there is no

easy yielding to despair.

Through all the horror and

hopelessness shines Mahler’s

unquenched belief in life:

the symphony stands as a

musical equivalent of the

poet Rilke’s ’dennoch

preisen‘ - ‘praising life nevertheless’.

Musically

speaking, the work stands

between two worlds, showing

Mahler as both the most

intensely romantic of the

late-romantics and the most

prophetic of modern

developments. There is no

paradox here: like all the

romantics, he was interested

in technical innovation not

for its own sake but for the

sake of emotional

expression. Just as Wagner’s

obsession with the

psychological conflict in

romantic love produced the

revolutionary chromaticism

of Tristan, so

Mahler’s own inner conflict

produced the breakdown of

tonality which is pervasive

in his Ninth Symphony. In

asserting his unquenched

vitality and praise of life,

he raised the passionate,

yearning element in the

romantic musical language to

its highest intensity; but

at the same time, in giving

vent to the bitterness and

irony in his soul, he

stepped up the tensions in

the more anguished type of

romantic expressionism until

it exploded into the

dissonance of our own time.

The towering

stature of the symphony,

however, lies in its

masterly formal

organisation, unifying the

two seemingly contradictory

styles; it is this which

transforms a subjective

personal document into an

objective universal

statement. But the work’s

length (strictly

proportionate to its

profusion of material) and

its complexity (integral

down to the last detail) are

such that the following

analysis can be no more than

a bare outline.

The four

movements follow an unusual

sequence, ending with a slow

movement, as in

Tchaikovsky’s ‘Pathetique’

and Haydn’s ‘Farewell` -

which are also ‘valedictory’

works. In fact, the

‘Pathetique’ was probably

Mahler’s overall model,

conscious or unconscious: in

that work, as in the Ninth,

the first movement is

followed by a steady dance,

a very fast march, and a

very slow finale. Mahler’s

four movements also follow

one of his favourite

procedures, a use of

‘progressive tonality’ to

emphasise the overall

emotional progression of the

work: the first movement is

in D major, but after the

two central movements, in C

major and A minor, the

finale does not return to

the bright key of D, but

moves down a semitone into

the darker key of D flat,

thereby emphasising the

final mood of farewell. Each

of the movements is

constructed on an individual

plan of Mahler’s own - a

kind of fusion of sonata

and/or rondo form with

variation form: various

sections of material

alternate, each returning in

varied form, and they are

subtly interwoven, each

taking in and varying

elements of the others. So

that where, in the following

analysis, one speaks of a

section returning, or of

sections alternating, it is

in this very special sense.

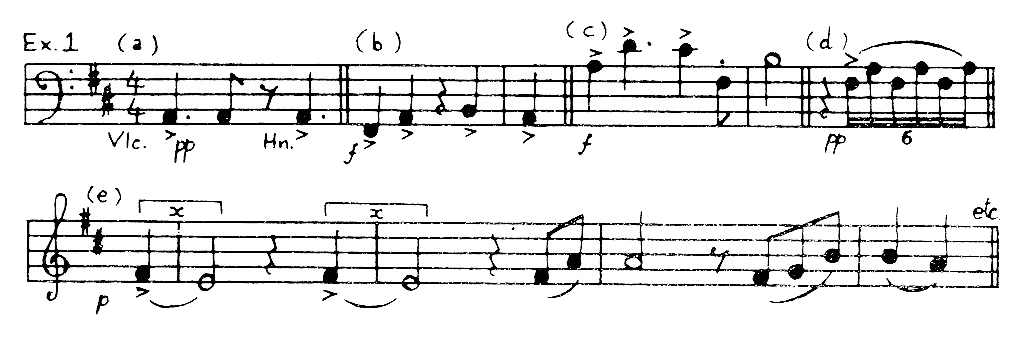

The opening Andante

Comodo - a

wide-ranging synthesis of

sonata and rondo forms which

is probably Mahler’s

greatest single achievement

- is an all-out battle

between three strongly

contrasted themes. But

first, a brief atmospheric

introduction (prophetic of

Webern in its sparseness of

texture and intangible

orchestration) sets forth

four basic ideas: these are

to permeate the movement,

and two of them are to

strike in devastatingly at

focal points in the

movement’s structure. Never

did a great symphony grow

out of more reticent

beginnings: the four ideas

are a halting rhythm like a

faltering heart-beat (Ex.

1a), a knell - like bell -

figure on the harp (Ex. 1b),

a sad phrase for muted horn

(Ex. 1c), and a fluttering

or palpitation on the violas

(Ex. 1d). Then, against this

mysterious background, the

second violins steal in with

the movement’s main theme,

based on two nostalgic

falling seconds (Ex. 1e).

This D major

violin theme is warm and

singing, redolent of the

Austrian summer which had

been for Mahler the constant

setting of his life as a

composer; it is filled with

a deep, tender longing,

which is too full of love of

life to be called Weltschmerz.

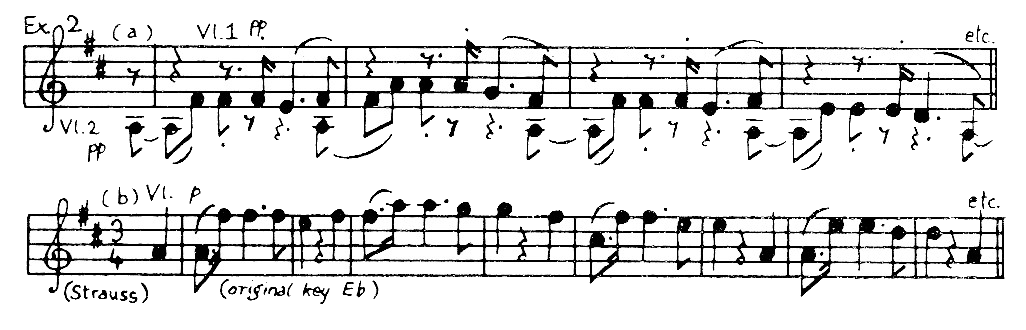

This is in fact the germinal

theme of the whole symphony;

and it has been pointed out

that,whether consciously or

unconsciously on Mahler’s

part, a version of it which

occurs later in the movement

(Ex. 2a) is a slow and sad

transformation of one of the

most ebullient of Johann

Strauss’s waltz-themes (Ex.

2b) - entitled,

significantly and

ironically, Freut euch

des Lebens (Enjoy

Life).

What is almost

certainly intentional is

that the main theme’s

falling seconds (Ex. 1e)

refer to the ‘farewell’

figure of Beethoven’s Les

Adieux piano sonata

(Ex. 3a). The reference is

made explicit later in the

movement, when the phrase

becomes identical with

Beethoven’s, and undergoes

the same kind of dissonant

canonic treatment-though the

dissonance is of course much

more acute with Mahler (Exs.

3b and c).

The initial

basis of the movement is a

conflict between the first D

major theme and the second,

jagged, upthrusting D minor

theme (Ex. 4), also for

violins, which is set on its

course by a sforzando

trombone chord and rises to

a high pitch of agitation.

This second

theme makes at first only a

brief appearance, as a

contrasting strain of the

first theme: it soon works

up to a climax, which is

surmounted by a broad

trumpet fanfare (Ex. 5).

The fanfare,

as can be seen and heard, is

a tragic transformation of

the two nostalgic falling

seconds of the main theme

(Ex. 1e); and immediately

the main theme takes over

again, its falling seconds

now expanded into great

downward-swooping ninths of

defiant joy.

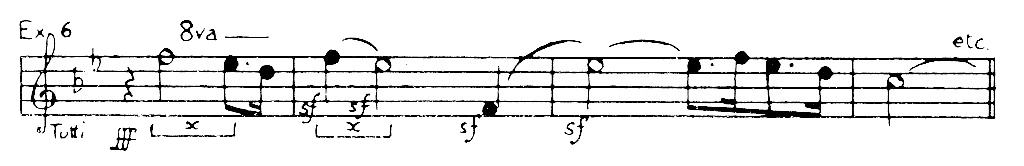

After this,

the second theme emerges on

its own, with a quickening

of the tempo; it again

reaches a desperate climax,

but this time jubilation is

wrung out of torment as a

new B flat major theme of

potent exultation enters the

conflict (Ex. 6).

This theme,

which acts as the true

‘second subject’ of the

sonata pattern, is clearly a

vigorous transformation of

the tragic trumpet fanfare

(Ex. 5) and thus of the

original nostalgic falling

seconds of the main theme

(Ex. 1e). Its climactic

entry achieves something

like a triumph, and the

exposition ends boldly. Yet

this ending sounds insecure;

and indeed, it is

immediately contradicted by

ominous, distorted

references to the ideas of

the introduction (Ex. 1),

which now open the

development. The main theme

emerges out of these shadows

(crossing the sonata pattern

with a rondo one, a

structural procedure which

continues throughout); but

this time it is interrupted

by agitated allegro

material based on the

trumpet fanfare (Ex. 5).

Again there is a desperate

climax, and again the

exultant theme (Ex. 6)

breaks through, but it goes

over into a sudden collapse,

followed by grotesque

mutterings in the depths of

the orchestra. The second

theme (Ex. 4) now takes

over, but it soon

disintegrates into extreme

dissonance (this is the

passage that includes the

explicit reference to the

theme of Beethoven’s Les

Adieux sonata, Ex. 3);

and again the main theme

steals back hopefully out of

the shadows. It soon gives

way, however, to the

exultant theme, and this now

sweeps everything before it;

it gradually rises to a

tremendous all-or-nothing

climax on the trumpets,

violins and high

woodwind-the peak of the

movement-only to go over

into a second, catastrophic

collapse, with the halting

rhythm and the knell-like

figure (Ex. 1a and b)

ringing out on trombone and

timpani like a dreadful

summons.

As Alban Berg

wrote: “The whole movement

is permeated with the

premonition of death, again

and again it crops up; all

the elements of worldly

dreaming culminate in it ...

most potently, of course, in

the colossal passage where

premonition becomes

certainty - where, in the

midst of the most profoundly

anguished joy in life, death

itself is announced ‘with

the greatest violence".

(‘With the greatest

violence’ is Mahler‘s

expressive marking against

the doom-laden

thundering-out of the

figures from the

introduction, which

interrupts the culminating

affirmation ofthe exultant

theme, marked by Mahler

‘with tremendous

intensity’.)

This point

marks the recapituiation

section of the sonata

pattern, but emotionally

speaking, the back of the

movement is now broken. As

so often with Mahler, the

size and emotional power of

the development section

makes possible only a

much-condensed restatement

of the material of the

exposition. As the

restatement of the

introduction continues,

mists obscure the scene, and

a funeral cortege passes by,

leading to the restatement

of the main theme for the

last time: as before, it

steals back, but now it

becomes shockingly

disfigured with extreme

dissonance. It merges into a

brief recurrence of the

second theme, which almost

immediately dissolves into a

shadowy, groping cadenza for

solo instruments.

Recapitulation has already

become coda: the

once-exultant theme is

referred to softly by a solo

horn, full of infinite

sadness, an echo of what

might have been; after

which, fragments of the main

theme slowly evaporate into

thin air.

Following the

emotional catastrophe of the

first movement, sardonic

mockery runs riot in the two

central ones. For his

scherzo movement, as so

often, Mahler used the

Ländler - the lilting

Austrian country waltz - as

a symbol of the dance of

life itself. But here the

lilt has vanished (Mahler’s

marking is ‘rather clumsy

and somewhat boorish’), and

the dance of life is seen as

something tawdry, cock-eyed,

and pointless. The main C

major Ländler theme (Ex. 7)

consists of fragments of

banal dance-tune, including

a sarcastic trivialisation

of the nostalgic falling

seconds of the first

movement’s main theme

(figure x): they are scored

with a grotesque dryness,

and made to trip over one

another awkwardly, in

country-bumpkin manner, in a

series of stumbling

repetitions.

The first of

the two trio-sections is a

crazy quick waltz, making

further sarcastic references

to the first movement’s

falling seconds; it

continues with brutally

vulgar trombone statements

of themes in the cheap

popular manner and includes

a brief scrambled reference

to the Ländler proper. Yet

in spite of this negative

vision, belief in life finds

its way back into the music:

the second trio-section,

following the first, is a

slower type of Ländler which

pleads for calm and

reflection by invoking the

first movement’s falling

seconds in their original

peaceful form on the violins

(Ex. 8).

This calmer

second trio-section is swept

away, however, by a violent

return of the first (Ex. 9);

and the movement now begins

to become a regular devils’

dance as this crazy music

treats the falling seconds

with ruthless irony,

involving them in a

disruptive modulatory

sequence (a chain of flat

submediant key-switches -

see figure y) and sneering

at them in an equivocal

phrase including a ‘Wagner

turn’ (figure z).

Both of these

features are to permeate the

rest of the symphony, with

the modulatory sequence

continually undermining the

tonal foundations of the

work. The rest of the

movement is an alternation

of the three different

elements; the end, as so

often with Mahler’s

scherzos, but here more

hollowly than ever, is an

eerie disintegration of the

main Ländler theme.

The Rondo

Burleske in A minor is the

most extraordinary movement

that Mahler ever composed,

and also the most modern,

continually foreshadowing

Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and

Hindemith, while remaining

pure Mahler nevertheless. He

marked it ‘very defiantly’,

and addressed it (privately)

‘to my brothers in Apollo’ -

by which he meant that it

represented a parody of the

clumsy counterpoint of those

fellow-composers who accused

him of having no

counterpoint at all. But

there is more than purely

musical animosity in this

music; the movement is an

outburst of malevolent

laughter at the apparent

futility of everything,

embodied in a fiendish

helter-skelter of dissonant,

disjointed counterpoint.

This contrived chaos is

built out of a myriad

fragments of theme, the most

important of which are shown

in Ex. 10.

The first

group is founded mainly on

10 a and b, which are

parodies, curiously enough

of the opening figures of

the third and second

movements of Mahler's own

Fifth Symphony (Ex. 11 a and

b).

This group

culminates in a madly

modulating march-tune based

on 10 c, but even this

movement of comparative

stability is soon submerged

in the general uproar. All

this alternates with a

second group, a kind of

trio-section based on 10 d,

which, as can be seen,

follows the same disruptive

modulatory sequence as the

waltz-theme of the second

movement (see Ex. 9). The

first group, on later

appearances, takes in new

material - 10 e and f, the

latter giving a vicious new

twist to the sneering phrase

with the ‘Wagner turn'

(figure z); the

trio-section, when it

recurs, throws in a scornful

parody of a cheerful

march-tune from the first

movement of Mahler’s own

Third Symphony (see Ex. 12 a

and b).

Yet once again

belief in life breaks

through: at last the

pandemonium is stilled by a

visionary interlude in D

major, looking back to the

key and the near-serenity of

the first movement’s main

theme. It is based on a

simple diatonic

transformation of the

grimacing Ex. 10 f on the

trumpet, which ennobles the

phrase with the ‘Wagner

turn’, and soon acquires a

supremely beautiful form on

the violins (Ex. 13).

But the first

group, after several

unavailing attempts, sweeps

this vision out of

existence, and ends the

movement in the nihilistic

mood in which it began.

As in

Tchaikovsky’s ‘Pathétique‘,

this swift third movement is

equivalent to the normal

rondo-finale, but the actual

place and function of the

finale is usurped by an

Adagio. And in Mahler’s

Adagio-finale, the glimpse

of peace amidst the inferno

of the Ftondo Burleske

becomes reality. The

movement transforms

bitterness into acceptance

and final serenity, though

in a heartbroken mood of

farewell. The transformation

is musical as well as

emotional: the note of

farewell is struck

immediately by the tonality

of D flat major - a semitone

lower than the D major of

the first movement - but the

main string theme, like a

passionate hymn to the glory

of life, is a gathering

together of the threads of

the whole symphony, in a new

context of affirmation (Ex.

14).

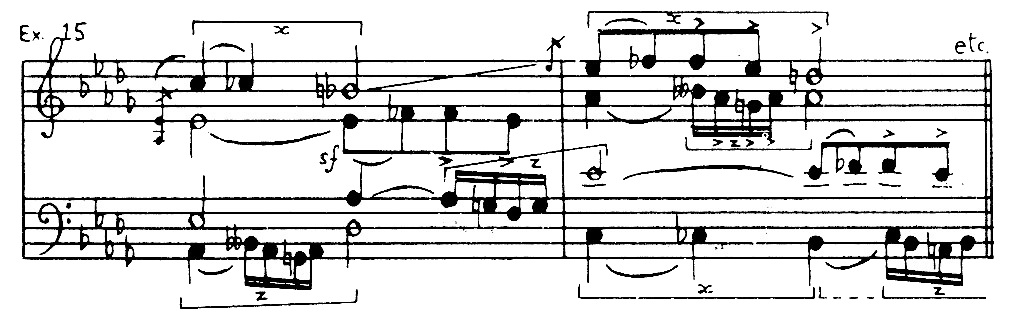

This theme

begins by conclusively

ratifying the first

movement’s reference to the

theme of Beethoven`s Les

Adieux sonata (figure

y), and thereby sets right

the travesties which have

been made of the nostalgic

falling seconds in the two

central movements. Moreover,

as a whole, the theme is a

noble transformation of the

crazy waltz-theme of the

second movement, as a glance

at Ex. 9 will show; and in

fulfilling this function, it

gives a restored dignity to

the phrase with the ‘Wagner

turn’ (figure z), which is

to permeate the movement.

What the theme is unable to

get rid of is the disruptive

modulatory sequence, which

continually tries to

undermine its tonality (see

first bar of Ex. 14); but it

surges forward all the time,

riding the disruptions, and

always emerging: with its

tonality finally unscathed.

For its second paragraph,

this main string theme

refashions the tragic

fanfare of the first

movement (Ex. 5) as a kind

of brave insistence on joy

out of the midst of

suffering (Ex. 15).

The second

group, extremely sparse in

texture, combines a few

wisps of disembodied theme,

utterly empty of feeling -

‘all passion spent’ (Ex.

16).

But passion

(the main theme) breaks in

again, alternating with the

second group in a

rondo-pattern, and ever

growing in intensity. It

undergoes many

transformations, including a

quiet episode based on the

visionary interlude of the

Rondo Burleske (Ex. 13) and

a heart-breaking climax on

the brass (a fortissimo

statement of Ex. 15); but at

last, it begins a slow,

lingering fadeout. It casts

back, as it were, a long,

steadfast, valedictory look

at life; the last long-drawn

line of the violins (Ex.

17a) refers, with great

poignancy, to the imagined

final dwelling of the dead

children in Mahler‘s own Kindertotenlieder

- ‘auf jenen Höh’n’ - ‘upon

those heights' (Ex. 17b).

© 1967, The

Decca Record Company

Limited, London

|