|

|

1 LP -

SET 555 - (p) 1972

|

|

| 1 CD -

414 066-2 - (c) 1986 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Das

Lied von der Erde |

|

64' 47" |

|

| - 1. Das Trinklied

vom Jammer der Erde |

8' 37" |

|

|

| - 2. Der Einsame im

Herbst |

9' 43" |

|

|

| -

3. Von der Jugend |

3' 08" |

|

|

| -

4. Von der Schönheit |

6' 56" |

|

|

| -

5. Der Trunkene im Frühling |

4' 22" |

|

|

| -

6. Der Abschied |

31' 51" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yvonne Minton,

contralto (2,4,6)

|

|

René Kollo,

tenor (1,3,5)

|

|

| Chicago

Symphony Orchestra |

|

| Georg SOLTI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Krannert

Centre of the University of

Illinois (USA) - maggio 1972 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

David

Harvey

|

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

Kenneth

Wilkinson, Gordon Parry

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Decca

ffss | SET 555 | (1 LP) | durata

64' 47" | (p) 1972 | Analogico |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Decca

| 414 066-2 | (1 CD) | durata 64'

47" | (c) 1986 | ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

The

Decca Record Company Limited,

London

|

|

|

|

|

SOLTI -

DECCA: SILVER JUBILEE

This recording

was made to celebrate

the25th year of Solti's

association with Decca as an

exclusive contract artist.

The many Decca recordings he

has made since 1947 have

included such classics of

the gramophone as his Ring

Cycle and Rosenkavalier.

A musician of wide

sympathies, his recordings

have included opera (notably

Wagner and Verdi),

symphonies of Beethoven,

Mahler and Schumann and

composers of his native

Hungary, Bartók and Kodàly.

It is with great pride that

Decca look back over an

association that has

produced such magnificent

results, and with eager

anticipation that we look to

its future.

DAS LIED

VON DER ERDE

Das Lied

von der Erde begins

Mahler’s "last period". All

artists undergo a process of

evolution in their creative

activity: Beethoven's "three

styles" correspond to three

ages of man, to three stages

of his thought and to three

evolutionary periods. In

this respect Mahler's case

is somewhat unusual, since

his creative life was

conditioned by his career as

an interpreter, man of the

theatre and administrator.

At the age of 20 he

discovered his style and

personality in Das

Klagende Lied, an

immediate and almost

miraculous revelation, for

even its instrumentation is

entirely original, despite

Mahler’s complete lack of

orchestral experience. Four,

and then eight years later,

two other important works

confirmed this early

promise: in 1884 came his Lieder

eines fahrenden Gesellen,

with orchestral

accompaniment (*) and then

in 1888, his First Symphony

(and the first movement of

the Second).

At the age of 28, therefore,

Mahler had few important

works to his credit.

Over-whelmed by the

difficulties connected with

his work as Director of the

Royal Hungarian Opera, he

only started composing again

in 1892 in Hamburg, where he

wrote the orchestral Lieder

of the Knaben Wunderhorn.

Finally he arranged to spend

his long summer holidays at

Steinbach, where he worked

in an isolated hut on the

edge of a lake, and the Second

and Third Symphonies

were composed there during

the next four years. His

appointment as director of

the Vienna Opera again

interrupted his creative

work for two years. In 1900

he decided to spend his

summers at Maiernigg, on the

Wörthersee: resuming his

"Sommerkomponist" (Summer

composer's) existence, he

finished his Fourth

there and from then on

composed his symphonies at

regular intervals: he

completed the most elaborate

of them all, the titanic Eighth,

in a remarkably short space

of time, one single summer.

The first four symphonies

are usually grouped together

in a first creative period,

known as that of the Knaben

Wunderhorn. Thus this

"first period" lasted almost

twenty years, from the Klagende

Lied to the Fourth

Symphony, while the

second, consisting of the

three "instrumental"

symphonies, V, VI, VII, only

lasted for four! The Eighth,

a hymn of love to all

mankind, unique in its

conception, form and style,

is in a category of its own,

in which the ardent

individualist, faithful to

romantic tradition, speaks

in the name of humanity.

Mahler had gone as far as it

was possible to go in this

direction and now fate was

to open up new perspectives

both for the man and for the

artist, forcing him to

consider the inner world of

human suffering. Despite his

miserable childhood, despite

the romantic literature

which had nourished his

youth, despite such tragic

works as the Sixth

and the Kindertotenlieder,

Mahler never gave way to

morbid introspection,

because of his many

activities as interpreter

and administrator. An

enthusiastic reader of

Dostoievski, he believed

sorrow and human misery to

be inescapable realities. He

was not "unhappy" in the

usual sense of the word,

despite the countless

enemies who surrounded him,

despite the failure of his

works, despite the scorn and

hatred which he aroused.

In 1907, when he was only

47, fate dealt him three

cruel blows which perhaps he

had already subconsciously

anticipated in the three

hammer-blows of the Finale

to the Sixth Symphony.

First Putzi, his favourite

daughter, died of scarlatina

and diphtheria; then a

doctor diagnosed valvular

malformation of Mahler’s

heart. The third blow was

his departure from the

Vienna Opera. This was a

great misfortune, for he was

as much a man of the theatre

as a composer, and he loved,

as well as hated, his stage

activities. In ten years he

had made the Vienna Opera

one of the great centres of

European music and he knew

that no comparable task

could ever be accomplished

elsewhere.

At the end of the summer of

1907, faced with the ruins

of his past, he read a

little book which he had

just received from Theobald

Pollak, an old and faithful

friend who kept a paternal

eye on both Mahler and his

wife, for Jakob Emil

Schindler, Alma Mahler's

father, had earlier procured

for him a good

administrative job. The book

was a selection of Chinese

poems translated into German

verse by Hans Bethge. Pollak

had suggested that they

could be set to music and

Mahler found much in common

between the poems and his

presentstate of mind.

Though he had been deeply

shaken by recent events,

Mahler did not feel that all

was over for him. He left

Vienna for New York, where

he conducted all winter at

the Metropolitan Opera, and

appreciated the many

encouraging aspects of his

new work: there was a

broad-minded outlook and

lack of prejudice in the new

world; there was financial

security which he needed to

compose in peace and live in

comfort with his family.

Certainly he met with bitter

artistic disappointments in

New York, but he came to

terms with life and

gradually regained his

strength. The real crisis

came in June 1908, when he

settled in Toblach, in the

southern Tyrol, and for the

first time had to forego his

greatest summer joys: no

more swimming or rowing, no

more long walks or bicycle

tours. "Not only have I

changed places", he wrote to

Bruno Walter, "but I must

alter my whole way of life.

You cannot imagine how

painful this is for me. For

many years I have been

accustomed to taking

strenuous exercise, to

wandering in forests and

over mountains, and boldly

wresting my ideas from

nature. I would sit down at

my desk only as a peasant

brings in his harvest, to

give shape to my sketches.

Even my spiritual troubles

disappeared after a good

walk (especially a climb).

Now I must avoid all effort,

watch myself constantly,

walk as little as possible.

At the same time, living as

I do in solitude and

concentrating on myself, I

feel more clearly everything

which is wrong with my

physical condition. Perhaps

I am looking on the dark

side, but since I have been

here in the country I have

felt less well than in town,

where distractions occupied

my mind."

Almost every year Mahler

went through this kind of

crisis when he turned to

composing after having

worked as an interpreter for

several months. But the

change had never been so

difficult. Bruno Walter, on

the advice of a Vienna

doctor, Feuchtersleben,

tactlessly suggested a

journey to Scandinavia; this

infuriated Mahler: "What is

all this nonsense aboutthe

soul and its sickness? And

where should I go to cure

it? ... To find myself I

need to be here alone. For,

ever since I have been

seized by this panic, I have

tried only to direct my eyes

and ears elsewhere. To

rediscover myself, I must

face the terrors of solitude

... I have in no sense a

hypochondriac's anxiety at

the thought of death, as you

suppose. I have always known

that I must die ... but all

at once I have lost the

serenity and clarity which I

had acquired. Once again I

am "faced with nothingness"

and at the end of my life I

have to learn how to walk

and how to stand upright all

over again. As far as my

"work" is concerned, it is

most depressing to have to

unlearn everything. I cannot

work at my table. I need

outside exercise for my

inner exercises. Your

doctor's advice is of no use

to me. After a gentle little

walk my pulse beats so fast

and I feel so oppressed that

I don't even achieve the

desired effect, which is to

forget my body ... As

superficial as it seems, I

repeat that this is the

greatest calamity which I

have ever known: I have to

start a new life as a

complete beginner."

According to Frau Alma, this

was the most dismal summer

the couple ever spent, since

all excursions and all

attempts at amusements

failed lamentably. "Anxiety

and sorrow" followed them

everywhere. Only his work

saved Mahler, and it was

thanks to it that he

"rediscovered himself". As

at Steinbach, he issued

strict instructions not to

be disturbed. He became so

immersed in his work that

one day he returned home,

pale and breathless: the

little maid Kathi had shown

the way to the Häuschen

to a visitor representing an

American piano firm, who had

shouted from a distance:

"Hello, Mr. Mahler." Mahler

had felt as if ”dashed down

from the towers of Vienna

cathedral".

On another occasion, a

jackdaw, pursued by a

falcon, broke a pane of

glass and took refuge in a

remote corner of the little

room, which was suddenly

filled with bird cries and

beating wings. l\/Iahler

came back to earth with a

start and only realized what

had happened when he saw the

jackdaw and the broken

glass. Like all romantics,

Mahler was an optimist, and

was much shaken by this

contact with Nature's

cruelty.

He finished the second part,

Der Einsame im Herbst,

at the end of July; then the

third, Von der Jugend

on the 1st of August; then

the first, Das Trinklied

vom Jammer der Erde on

the 14th; then the fourth, Von

der Schönheit on the

21st and finally the last, Der

Abschied on the first

of September (1).

His summer visitors found

Mahler much changed: he was

calmer and more patient; he

had accepted his fate. The

spiritual experience which

he had just undergone is

fully expressed in Das

Lied as well as his

new discovery of the world's

beauty. "I was full of zeal

(and you will thus realize

that I have become

acclimatised"). I cannot

say myself what the

whole thing will be called.

I have had some good moments

and I believe this is quite

the most personal thing I

have done up to now". In

these terms he wrote to

Bruno Walter to announce the

work's completion;

immediately afterwards he

started sketching the Ninth

Symphony. During the

winter, having returned to

the Metropolitan Opera, he

copied the sketches and

finished the orchestration.

The work still lacked a

title. He considered "Song

of the Sorrow of the Earth”,

and then, one day at the

Savoy Hotel, he jotted down

on a sheet of paper "Song of

the Earth, from the

Chinese". He added all the

present titles, with the

exception of the fifth

section, to which he gave

the same name as the poem, Der

Trinker im Frühling

(The Springtime Drinker);

the final title was to be Der

Trunkene (The Drunken

Man) (2). On the

same page he wrote ”Ninth

Symphony in four movements",

which proves that the two

works were simultaneously

conceived. The final title,

"Symphony for tenor and alto

(or baritone) and orchestra"

only appeared later. Either

Mahler did not at once

realize the "symphonic"

character of his cycle, or

he hesitated to call it a

symphony, because neither

Beethoven, nor Schubert, nor

Bruckner had outlived this

fatal number nine;

superstition was responsible

for this attempt to outwit

fate.

For a long time it had been

Mahler’s principle never to

set "great" poems to music,

since they are already

perfect on their own. Thus

he always searched for texts

which music could complete

or reveal. It is not

surprising that Bethge

attracted his attention, for

his concise and refined

Chinese poems recalled those

of Rückert, who drew his

inspiration from oriental

sources and had inspired

many of Mahler’s songs.

Nevertheless, why did Mahler

express in symphonic terms

thoughts of such an intimate

and personal nature? No

doubt the Symphony was his

form of expression and the

orchestra his instrument,

and the poems awoke many

echoes of his past, thus the

whole work became the

symphonic embodiment of

mankind's tragic destiny.

The 24 year old poet who

wrote, in Cassel:

Und müde

Menschen schliessen ihre

Lider

Im Schlaf

auf’s Neu, vergess'nes Glück

zu lernen! (3)

could not fail to be

moved when he read in Bethge

(Mong-Kao-Jen)

Die

arbeitsamen Menschen

Geh'n

heimwärts, voller Sehnsucht

nach dem Schlaf. (4)

This was not an

unconscious rapprochement:

Mahler did in fact alter

"arbeitsamen" to "müden" and

inserted from his youthful

poem the phrase "vergess’

nes Glück und Jugend neu zu

lernen".

Mahler, the eternal wanderer

("fahrende Gesell") was

"three times without a

country: a Bohemian among

the Austrians, an Austrian

among the Germans, and a Jew

among all the other peoples

in the world". He was also

isolated as an artist among

human beings and was

naturally drawn to Wang

Wei’s poem:

Wohin ich

geh’ ? Ich wandre in die

Berge

Ich suche

Ruhe für mein einsam Herz, (5)

Since he knew no

Chinese, Hans Bethge

(1876-1946) used French,

German and English

translations for his

adaptations of 83 variously

dated poems (6). The

charm of the originals is

quite faithfully preserved

although here and there the

adapter added a

(1)

Only the date on which he

finished the fifth section

is unknown, since the

manuscript has not been

found.

(2) This page belongs to

Dr. Hans Mildenhauer, of

the University of

Washington, Seattle,

U.S.A.

(3) And weary men close

their eyes to find again,

in sleep, forgotten

happiness!

(4) Weary men wend

homewards - Longin g for

sleep.

(5) Whither I go? I go, I

wander in the mountains -

I seek rest for my lonely

heart!

(6) The poems of the

second, third and fourth

parts are to be found in

Judith Gauthier's

anthology Le Livre de

Jade; others in Poesies

de l'Epoque Tchang by

Count Hervey

Saint Denis.

few romantic touches which

cannot have displeased

Mahler. Among the poets

translated by Bethge, the

most famous is Li-Tai-Po

(701-762), academician and

high official at the

Imperial court, and above

all a poet of genius who

could express perfectly in

words both the most powerful

and most delicate feelings,

'His contemporary, Wang-Wei,

painter and poet, expressed

sentiments which were even

closer to Mahler: in his

farewell poem, which ends

the work, he longs for peace

(”Ich suche Ruhe für mein

einsam Herz") (7).

Tchang-Tsi, in the second

piece, exclaims: "Mein Herz

ist müde" (8). In

the first, Li-Tai-Po sings

of the shortness of life and

its sorrow ("Dunkel ist das

Leben") (9). The

lonely Tchang-Tsi

contemplates flowers bent

over by autumn storms

(Mahler had the same vision

in 1895 while composing the

innocent minuet in the Third

Symphony). As in the

first Lied eines

fahrenden Gesellen, a

bird announces the coming of

Spring to Li-Tai-Po (fifth

section) in the very words

used by the 20 year old

Mahler in the poem he sent

to Anton Krisper and the

libretto of his opera Rübezahl.'

”Der Lenz ist da, der Lenz

ist kommen". (10)

The Chinese poems of the

Chinesische Flöte

also praise both the Earth,

which gave the work its

title, and Nature, one of

Mahler's greatest sources of

happiness and inspiration:

in the Third Symphony,

this love took on an almost

pagan and pantheistic form,

but even at the age of 17,

Mahler already emphatically

invoked the spirit of the

Earth in one of his letters:

”O meine vielgeliebte Erde,

wann, ach wann, nimmst du

den Verlassenen in deinen

Schoss. (11)" "The world

fills me with joy! How

beautiful it is!" he said to

Ernst Decsey in Toblach

during the summer of 1909.

This joyous ecstasy

counterbalances the sombre

and disillusioned mood of

the Lied von der Erde.

I know of no other musician

who composed only Lieder

and Symphonies, two

apparently irreconcilable

genres. This double vocation

remains the central,

fundamental problem of

Mahler's style. In it there

is a kind of osmosis, a

mutual enrichment of two

different trends. Their

essential characteristics

can be approximately defined

and contrasted as follows:

Lied

Voice always

in the foreground

Melodies complete in

themselves and seldom

altered

Accompaniment based on

simple figures

Elementary static form,

strophic and akin to Rondo

Piano and Voice

Symphony

Melodies and

countermelodies

Variable melodies

constructed around motifs

No realaccompaniment

Complex Sonata form

developed dynamically from

motifs

Orchestra

Even in his youth, Mahler

constructed his Lieder

with exceptional care and

used unusually strict

methods of composition: he

already constructed and

developed motifs and never

improvised to suit the

texts. He intensely disliked

Hugo Wolf’s Lieder

which he considered

formless. On the other hand,

lyricism, so successfully

introduced by Schubert into

the symphony,

counterbalanced in Mahler's

work the German tradition

and the dynamic trend of

Beethoven and Wagner. A work

such as Das Lied

appears at first sight to be

of a purely lyrical nature,

yet on closer examination it

turns out to be as much the

work of an architect as of a

poet. Yet Mahler's

orchestral style remains

deliberately vocal, even for

such instruments as brass

and percussion.

Mahler's first symphonies

drew much of their substance

from his Lieder: the

First, the Second,

the Third and the Fourth

borrow themes and even whole

movements from them. In the

succeeding symphonies the

relationships and exchanges

are more subtle, but equally

clear. With the Song of

the Earth, Mahler

became the innovator

of a new form which was both

an amplification of the Lieder

cycle, a "Symphony of Lieder"

and a Symphony in the usual

sense of the word.

Though the work as a whole

breaks new ground, some

passages in Das Lied von

der Erde recall

earlier compositions. The kleine

Lampe in the second

part recalls that of the

first Kindertotenlied;

in the three graceful

intermediate sections

Mahler's style is not

unrelated to that,

half-naïve, half

caricatural, of the Wunderhorn

Lieder. Here the

symphonist no longer defies

fate as in the Fifth

and Sixth Symphonies.

Like Schubert in the Winterreise,

he is resigned to his

destiny, with all its joy

and bitterness, its

happiness and disillusion,

and its end which is the

same forall men.

From a technical point of

view, the novelty of the

work is

(7) I

seek rest for my lonely

heart.

(8) My heart is weary.

(9) Dark is life.

(10) Spring is here,

Spring has come.

(11) Oh my beloved Earth,

when, oh when wilt thou

take the forsaken one unto

thy bosom?

striking. A new method

of composition had gradually

been evolved by Mahler: in Das

Lied he constantly

alters and varies his

motifs, inspired by life

never to repeat himself. Now

everything, even the

accompaniment, is

melodic. The "linear

polyphony" of the Lied

von der Erde

sometimes seems to

hover between heaven

and earth, and points

strikingly towards

Schönberg's "all

thematic" or

”perpetual variation"

techniques. Thus the

fundamental problem of

music, that of unity

and diversity, has

found a new solution.

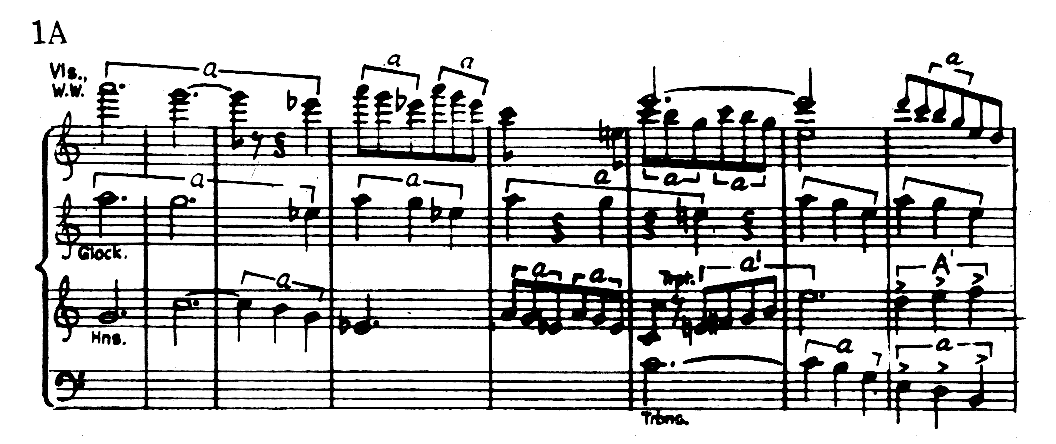

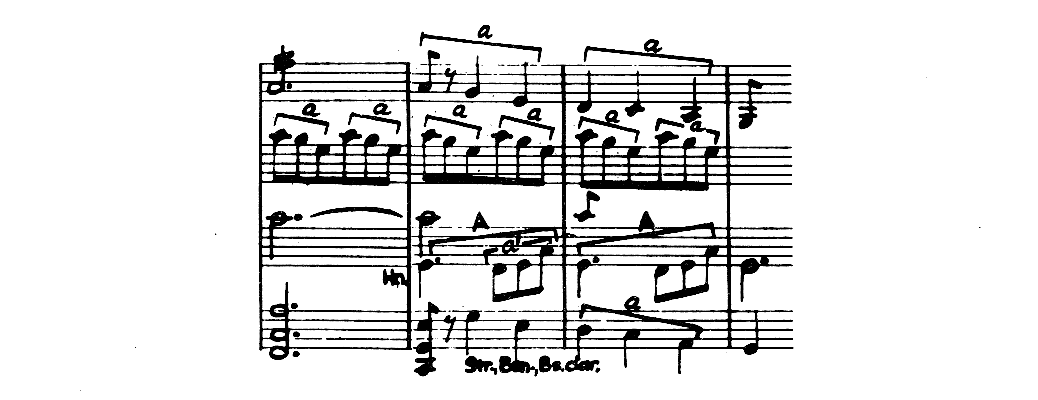

A single passage in

the first section

reveals the essential

features of this

technique:

The structure of the work is

simple and exists in other

Mahler symphonies: the first

and last movements are

separated, as in the Seventh,

by Intermezzi. The

first Lied into

which the eminent Mahlerian

Deryck Cooke has read the

essential features of Sonata

form, appears to me rather

as a strophic Lied

in which each stanza

contains variations. The andante

is followed by three intermezzi

or scherzi and for

the first time since the Third

Symphony, by a long,

slow Finale,

probably modelled on that of

the Walkyrie, rather

than on the

variation-Finales of

Beethoven's Sonatas op. 109

and 111. The first movement

is dynamic, but its

outbursts of joy are

somewhat forced, since the

poet sings of drunkenness as

a supreme remedy for all

ills. The second movement is

a sombre autumnal reverie:

the poet longs for rest and

eternal peace. The three

next movements recall a

happy past. In the last, Der

Abschied, the musician

widens and amplifies the

meaning of the poem, seeming

to say farewell to life. The

mood alternates between

boundless sorrow and lyrical

ecstasy caused by the

contemplation of nature. The

conclusion transcends all

reality: it is a promise of

eternal life, a kind of

"redemption through

suffering". We are far from

the Christian idea of

resurrection which provided

the Second Symphony

with its glorious ending:

the redeeming light seems to

come from Nature; Mahler

wrote the text himself:

The

beloved earth everywhere

Blossoms

in Spring and grows green

again!

Everywhere and eternally the

distance shines brightand

blue!

Eternally... Eternally...

Mahler kept the finished

score of Das Lied von

der Erde for two

years: the work touched him

so deeply that he spoke

little about it. He did

however give the manuscript

to his favourite disciple,

Bruno Walter. When Walter

returned it, moved beyond

words, Mahler only pointed

to the Abschied:

“What do you think of it? Is

it at all bearable? Will it

drive people to do away with

themselves?" Then he smiled

and showed Walter some

rhythmic difficulties in the

same piece: "Do you have any

idea how to conduct this? I

haven't!"

Before he could make up his

mind to have the work

performed, Mahler died. Six

months after his death, it

was Bruno Walter who

conducted the first

performance in Munich, on

the 20th of November 1911,

in a concert dedicated to

Mahler's memory. Few

posthumous messages can have

ever borne more striking

witness to the genius of a

departed master.

(*) One of

the earliest manuscripts

proves that the

accompaniment was

immediately conceived for

orchestra.

by Henry-Louis

De La Grange

Translated by Johanna

Harwood

© 1967 The

Decca Record Company

Limited, London

|

|