|

| 1 CD -

8.43774 ZS - (c) 1987 |

|

1 LP -

6.42174 AW - (p) 1977

|

|

CEMBALOWERKE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Girolamo FRESCOBALDI

(1583-1643) |

Toccata

Decima |

aus "Toccate

d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo et

Organo, Partite di diversi arie et

Corrente, Balletti, Ciaccone,

Passachagli, di Girolamo

Frescobaldi, Organista in S.

Pietro di Roma - Libro Primo,

1637" |

|

4' 33" |

1

|

A1 |

|

Cento Partite

sopra Passacagli

|

aus "Toccate

d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo et

Otgano Libro Primo 1637" |

|

11' 35" |

2 |

A2

|

|

Canzona Terza

|

aus "Il secondo libro

di Toccate, Canzone, Versi

d'Hinni, Magnificat, Gagliarde,

Correnti et altre Partite

d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo et

Organo di Girolamo Frescobaldi,

Organista in S. Pietro di Roma,

1637" |

|

3' 44" |

3 |

A3

|

|

Toccata Nona

"Non senza fatiga si giunge al

fine"

|

aus "Il secondo

libro di Toccate... 1637" |

|

5' 16" |

4 |

A4

|

|

Capriccio sopra

la Bassa Fiamenga

|

aus:

"Il primo libro di Capricci, Canzon

francese e Recercari fatti sopra diversi

soggetti, et Arie in partitura,

1626/1642" |

|

5' 20" |

5 |

B1

|

|

Toccata Nona |

aus "Toccate

d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo et

Otgano Libro Primo 1637" |

|

6' 07" |

6

|

B2 |

|

Canzon Terza

detta La Crivelli

|

aus:

"Canzoni alla francese in partitura del

Signor Girolamo Frescobaldi, Organista

di S. Pietro di Roma, Raccolte

d'Allessandro Vincenti - Libro quarto,

1645" |

|

1' 36" |

7 |

B3 |

|

Partite 14

sopra L'Aria della Romanesca

|

aus "Toccate

d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo et

Otgano Libro Primo 1637" |

|

13' 33" |

8 |

B4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Bob

van ASPEREN, Cembalo (Martin

Skowroneck, Bremen 1964, bach einem

italienischen Instrument des 17.

Jahrhunderts)

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

-

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

-

|

|

|

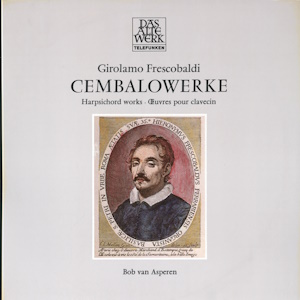

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken

- 6.42174 AW - (1 LP) - LC 0366 -

durata 51' 44" - (p) 1977 -

Analogico

|

|

|

Edizione

"Reference" CD

|

|

Tedec

- 8.43774 ZS - (1 CD) - LC 3706 -

durata 51' 44" - (c) 1987 - AAD |

|

|

Cover |

|

Detail

aus einem barocken Bilderrahmen

mit König David, Musen, Tugenden

und Lastem. Buchsbaumholz /

Holland gegen 1670, mit

freundlicher Genehmigung des

Museums für Kunst und Gewerbe,

Hamburg

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The

Italian composer

Girolamo Frescobaldi

(1583-1643) was admired

and revered by his

contemporaries as a

brilliant singer, a

powerful organ and

harpsichord player and

an extraordinary

improvisor. If one can

believe the chroniclers

of yesteryear, his organ

playing (Frescobaldi was

organist at the famous

St. Peters cathedral in

Rome for the last 35

years of his life)

attracted masses of

listeners — sometimes as

many as 30,000 people.

Frescobaldi’s compatriot

and contemporary

Severino Bonini

(1582—1663), one of the

earliest exponents of

the monodic style,

testified to his

considerable reputation

as a practising musician

with the pithy remark:

‘‘Nowadays anybody not

playing according to his

style is not

appreciated”. Another

indication of the

considerable esteem in

wich Frescobaldi was

held also as a composer

during his lifetime is

the fact that the

important composer and

Vienna court organist

Johann Jacob Froberger

(1618-1667) — regarded

as the founder of the

piano suite — studied

for four years with his

older Italian colleague

at the court’s expense.

Although

the image of a brilliant

music personality might

today appear to have

paled somewhat, due to

the enormous distance in

time of three and a half

centuries, the

historical significance

of the most important

representative of early

baroque Italian

instrumental music is by

no means underestimated

by musicology. Thus

Girolamo Frescobaldi is

justifiably regarded as

the great renewer of

Italian instrumental

music at the beginning

of the 17th century, who

combined the polyphonic

techniques and

instrumental forms of

his predecessors Andrea

Gabrieli, Claudio Merulo

and Giovanni Gabrieli in

his work and further

developed them into new

musical qualities.

Together with Claudio

Monteverdi, who in the

field of vocal and

operatic music achieved

epoch-making

significance, it was

Frescobaldi with his

brilliant creative

spirit who led Italian

instrumental music

‘‘from the academic

strictness of form of

the renaissance period

to the strength of

expression, liveliness

and finely jointed

structure of the early

baroque style” (Claudio

Sartori).

Compositions

for organ make up the

most important part of

Frescobaldi’s

wide-ranging creative

work. However, the works

for harpsichord also

play a major role, both

as regards quantity and

quality. Many of his

works — which have been

preserved in exemplary

original printings in

tablature form (i.e., in

the six and eightline

system) and partly also

in copies — were

expressly intended by

Frescobaldi himself to

be played by harpsichord

and organ (“DI CEMBALO

ET ORGANO")

The range

of forms to which

Frescobaldi had recourse

is also diverse. In

addition to Ricecar,

Canzon and Fantasia

- predecessors of the

fugue - there are the

forms of the Toccata,

the Capriccio

and of the Partita.

In his hands these

traditional forms are

developed into artistic

formations of strong

structural uniformity

and major formal

integration. In their

occasionally rich

chromatics and colourful

harmony, their richness

of inspiration and in

their technical

performance virtuoso

style, these works have

maintained their

unbroken effective

strength across the

centuries.

The

present gramophone

record spotlights

Frescobaldi’s

interesting piano style

in the forms of the

Canzone, Capriccio, the

Toccata and of the

Partita. Typical for

Frescobaldi’s canzoni

(examples):

"Canzona

Terza”’ from the “Second

book of toccatas,

canzoni...” and the

“‘Canzon Terza detta la

Crivelli” from "Canzoni

alla Francese’’) are, in

addition to the

development of fugue

expositions, a varied

but nevertheless clearly

structured overall form,

evenly flowing motion,

colourful harmony

influencing the entire

construction and the

adherence to a single

theme which returns in

changing shapes in every

section. This type of

“Variations Canzone”

developed by Frescobaldi

now replaced the former

“‘Contrast Canzone" of

the renaissance.

The

Capriccio, which in form

is related to the

Canzone (example:

‘Capriccio sopra la

Bassa Fiamenga'' from

the ‘First Book of

Capricci, Canzoni and

Ricercare .. ."')

displays greater

independence in

arrangement compared to

the other forms. In

content it is freer and

more multifaceted, and

at the same time clearly

indicates varied

compositional and

performance practice

intentions and emotions.

In the

Toccatas (examples:

“Toccata Nona” and

‘Toccata Decima" from

the “First Book of

Toccatas and Partitas”

and ‘“Toccata Nona” from

the “Second Book of

Toccatas and Partitas. .

."') Frescobaldi reveals

his magnificent art of

playing which was so

greatly admired by his

contemporaries, as

already referred to. The

frequent change from

broad chordal surfaces,

strongly figured and, in

some cases, virtuoso set

passages, as well as

imitative sections

results in wider

emotional diversity and

creates dramatic

tensions.

English

and Dutch variation

techniques, with which

the young Frescobaldi

became acquainted at

first hand during his

stay in Flanders

(1607/08) are reflected

in the Partitas

(examples: “Cento

Partite sopra

Passacagli” and "Partite

14 sopra l'Aria della

Romanesca'' from the

‘‘First Book of Toccatas

and Partitas.... .""). A

musical speciality is

the *'Partite sopra

Passacagli"' with its 14

variations. In this work

elements of the

variation, of the suite

and of the passacaglia

amalgamate to become

music of grand formal

compactness.

A word on

the interpretation of

the Frescobaldi works.

The composer prefaced

his various books of

organ and keyboard works

which appeared in print

with remarks which

contain some revealing

advice on the

interpretation of his

pieces. For instance he

placed especial

importance on a style of

performance which

accorded with the

particular form and the

appropriate tonal

character. Among other

things, he demanded that

the “‘style of play . .

. should not be rigidly

subordinated to the

measure”; which meant

that ‘“‘the measure

should now be played

slowly and then quickly,

or then even suspended,

according to the

expression or meaning. .

.” In the demand for a

“fully expressive’,

“‘lively’’ and

“tasteful”

interpretation,

Frescobaldi thus became

the precursor of an

interpretation style

which was to find its

most consistent

realisation in the

individual rubato

playing of the

nineteenth century.

Siegmar

Keil

English

translation by

Frederick A. Bishop

|

|