|

| 1 CD -

8.44009 ZS - (C) 1988 |

|

| 1 LP -

6.42705 AZ - (p) 1981 |

|

LAUTENMUSIK DER RENAISSANCE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Matthäus WAISSEL

(um 1540-1602) |

Tänze aus

"Tabulatura" (1573)

|

|

6' 48" |

1 |

A1

|

|

- Tantz ·

Sprunck · Tantz · Tantz · Tantz

· Sürinck |

|

|

|

|

| Valentinus BAKFARK

(1507-1576) |

Fantasia I (a

vocum) aus "Intabulatura" (Lyon

1553) |

|

3' 05" |

2 |

A2

|

| ANONYMUS |

Tänze aus:

"Danzinger Manuskript" (17.

Jh.) |

|

4' 24" |

3 |

A3

|

|

"Danza"

und "Pezzo Tedesco" (16. Jh.) |

|

2' 17" |

4 |

A4

|

| Valentinus BAKFARK |

Ung gay bergier

(nach Thomas Créquillon) aus

"Intabulatura" (Lyon 1553) |

|

2' 29" |

5 |

A5

|

| ANONYMUS |

Tänze aus:

"Vietórisz-Manuskript" (17.

Kh.) |

|

5' 31" |

6 |

A6

|

|

- Olach Tantz

· Mascarada · Bergamasca ·

Polonica

|

|

|

|

|

| Francis

CUTTING (17. Jh.) |

Gaillard |

*

|

1' 38" |

7 |

B1

|

| John

DOWLAND (1563-1626) |

Melancholy

Gaillard

|

* |

2' 21" |

8 |

B2 |

|

Allemande

"My lady Hunssdon's puffe"

|

* |

1' 28" |

9 |

B3 |

| Baruch

BULMAN (16. Jh.) |

Pavan |

* |

3' 28" |

10 |

B4 |

| Melchior

NEWSIDLER (1531-1591/92) |

Der Fuggerin

Tantz aus "Teutsch

Lautenbuch" (1574) |

|

1' 01" |

11 |

B5 |

| Hans

NEWSIDLER (1508-1563) |

Gassenhauser |

|

1' 04" |

12 |

B6 |

|

"Wascha mesa"

und "Der Hupff auff" aus

"Ein newgeordent künstlich

Lautenbuch" (1536) |

|

1' 55" |

13 |

B7 |

| Francesco

DA MILANO (1497-1543) |

Ricercare 23

|

|

3' 06" |

14 |

B8 |

| Joan

Ambrosia DALZA (um 1500) |

Pavane alla

Ferrarese

|

|

1' 39" |

15 |

B9 |

|

Saltarello |

|

1' 49" |

16 |

B10 |

|

Piva |

|

0' 57" |

17 |

B11 |

| Valentinus BAKFARK |

Or vien ca vien

(nach Clément Janequin) aus

"Intabulatura" (Lyon 1553)

|

|

3' 39" |

18 |

B12 |

|

|

|

|

|

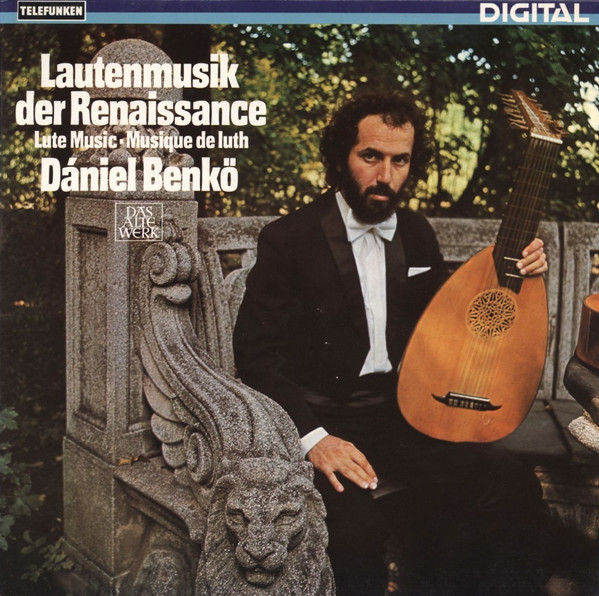

| DÁNIEL

BENKÖ, Laute, Orpheoreon* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

- |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken

- 6.42705 AZ - (1 LP) - LC 0366 -

durata 50' 08" - (p) 1961 -

Digital |

|

|

Edizione

"Reference" CD

|

|

Tedec

- 8.44009 ZS - (1 CD) - LC 3706 -

durata 50' 08" - (c) 1988 - DDD |

|

|

Cover |

|

"Gitarrenspielerin"

aus der Serie "Musiksoli",

Porzellan. Modell von J. Chr. W.

Beyer, Ludwigsburg um 1765/66.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe,

Hamburg.

|

|

|

|

|

About

Myself

Though I was given an

instrument (a violin)

when I was six, I never

thought of becoming a

musician - indeed I

preferred everything to

practising the violin.

So much so that,

following a family

tradition, I almost

became a dancer - but in

came the “beat” era and

under this influence I

began, at 15, to play

the guitar in a group. I

founded various : pop

groups in which I played

bass guitar or solo; but

eventually I got mixed

up with classical again.

I finished the Béla

Bartok Conservatory, |

Budapest, as a

guitarist, and went on

to the Budapest “Ferenc

Liszt” Academy of Music,

where I got a degree in

guitar. But even after

this I. was not sure if

I’d be a guitarist or

not, because just after

finishing I met a lutist

by chance: this was the

first occasion I heard a

lute “face to face”

(Lwas 24 then!). I

decided to play the lute

myself I attended lute

courses in England and

Holland (led by Eugen M.

Dombois and Diana

Poulton) and in a short

time it turned out that

the lute was my

instrument. But it came

to light in a couple of

years that the guitar,

too, was among my

instruments; gradually I

started playing more and

more instruments, the

orpharion, vihuela,

Baroque lute, Baroque

guitar, oud, etc. During

one concert I normally

change instruments - on

such occasions I arrive

equipped like this (see

illustration No. 2).

In 1972 I founded the

Bakfark Consort, and a

few years later the

Benkö Consort. With

these ensembles I play

music from Eastern and

Western Europe, from the

13th to the 19th

century. I also did

teaching at a time,

including giving lute

lessons at the “Ference

Liszt” Academy of Music

in Budapest.

Occasionally I give

courses, as I did in

Kloster Langwaden, and

as I do in Groznjan,

Yugoslavia. I started

recording in my second

lute-playing year, among

other things the

complete lute works of

Balint Bakfark, the

first of which was

chosen “Pick of the

Year” by the London

magazine “Record and

Recording”. I also did a

number of records with

my ensembles. Besides

theoretical work

(writing articles and

publishing music) I

travel around the world:

alone, with many

instruments; and with

the ensembles, with even

more instruments. And as

I said above in the

sleevenotes: I play pop

music. I started as a

“beat” musician and I

still claim to be one:

the pop musician of

bygone ages.

We might as well have

called this record

“Renaissance Pop Music”,

for the selection brings

together some of the

most popular melodies

and international themes

of the 16th century:

dances and fantasies

which, during that

century, were just as

popular as is a Beatles

or a Donna Summer tune

these days. They were

sung (or danced to, as

the case may be) from

Italy to England, from

the court of Burgundy to

the royal castle of

Cracow. Though one dance

sprung from German soil,

another from Italy, or

Hungary, or far-away

England, they have a

good deal in common as

in that age musicians

spoke one international

language making it

possible for one melody

to appear, and become

popular, in various

cultural centres of

Europe no matter where

its original had come

from: in a few decades

it lost its national

characteristics. The

best example for this is

“Danza und Pezzo

Tedesco” (Anon.); both

dances are of the

allemand-type, both come

from Italy, but the

second clearly shows its

German origins. (These

were first published by

O. Chilesotti.) We finda

very similar rhythm and

melody in the Lublin

Tablature Book around

1540, or in Heckel’s

1572 collection. Various

manuscripts from Prague

contain a similar dance

entitled Bathori Tanz,

which obviously points

to a Hungarian or Polish

origin - but this rhythm

and dance makes its way

as far as France: we may

recognize our piece in

the Branle de Bourgogne

of Claude Gervaise’s

collection of 1556.

The opening melody of

the record is probably

the most popular one of

the 16th century. Its

original (mind you, what

is “original” ?) title

is “Ich gieng einmal

spacieren” - but the

theme appears under a

bewildering number of

titles, e.g. “Almande

Nonnette” in the

Netherlands, “The

Queen’s Alman” in

England, “La Monicha”

and “Celeste Giglio” in

Italy; in France its

names are “Une jeune

fillette” or “Une vierge

pucelle” or “Ma belle

siton”. There is also a

church version: “Helft

mir Gott’s Güte

preisen”. Whether this

tune was born as

instrumental with the

lyrics added later (as

they have been

preserved) or the

original had words which

later some composers

omitted, we do not know;

but the same is true for

a lot of Italian, French

and Dutch instrumental

music whose titles

suggest a song original

with lyrics that later

got lost. The publisher

of this item was

Matthäus Waisselius”

(Waissel) a

German-Prussian lute

teacher and performer.

These activities

naturally went together,

a lutist did all jobs:

he searched for old

melodies by other

composers, adapted them

or included them in his

collection (plagiarism

had not been invented

yet), but he also

composed music himself,

and performed his works

travelling the world -

provided, of course,

that he was among the

successful. Waisselius

surely was, for he

published four grand

collections at

Frankfurt-on-the-Oder

between 1573 and 1592.

Most of the pieces are

works by others, but he

is very fair in quoting

their names, e.g.

Lassus, Bakfark, etc.

The dances on our record

may be of folk origin or

may have been composed

by Waisselius himself;

it was not customary to

indicate the composer of

such short pieces at

that time. These dances

are from the

“Tabulatura” of 1573, an

enormous collection of

52 pieces: fantasies,

dances, intabulations,

transcriptions. I

selected this suite-like

medley of dances quite

arbitrarily, at time

omitting the proportio,

at time playing the

proportio only: I don’t

think the author would

have insisted on having

them performed in their

order of printing.

Waisselius adds little

figuration to the

dances, compared to his

passamezzos and

intabulations. He does

not print out the

repetitions but merely

indicates them; thus I

necessarily had to

create the figurations

myself, following the

model of Waisselius’s

other works. A few

decades after the

flourishing of

Waisselius the “Danziger

Manuskript”, the famous

manuscript of Gdansk (MS

4022) was produced,

which included some of

his works as well as

several Western European

(chiefly French and

Italian) dances.

Unfortunately this

collection got lost

during World War II, and

only some pieces of

which transcripts had

been made before the war

are now known. It is

from these that I have

selected some. The first

has a melodical relation

to Hungary, the last is

a typical Polish dance

in 3/4, with the stress

on the second fourth.

The number preceding it,

in 3/4 and minor key, is

related to another piece

on this record: the

“Melancholy Galliard” by

Dowland - itis actually

a folia-theme, a variant

of that one.

Closely attached to the

Danzig Tablature Book is

the “Vietorisz-Codex”,

which is also from the

early 17th century; the

music, however, is

renaissance much more

than baroque. (In

Hungary, music was

generally written down

with a time lag of 100

to 120 years, owing to

the long lasting Turkish

occupation.) This

manuscript of tablatures

(Ammerbach organ

tablature), containing

about 400 melodies,

church and secular,

instrumental and vocal,

is the largest such

collection in Hungary,

presenting an all-round

picture of the repertory

of the provincial home

music of its period. It

has Turkish melodies as

well as Slovak,

Rumanian, Polish and

Hungarian music, a

couple of Western

European dances, church

and folk songs, and

flower (love) songs. The

collection passed

through many hands till

eventually it got to the

Library of the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences.

Itused to belong to the

Vietörisz family, hence

the name. You may wonder

how these pieces,

written down in organ

tablature, have been

included in a lute

recital record, among

original compositions.

But consider that there

were several such

tablature books in

provincial Hungary, and

there are indications

that any musician was

expected to play from

such an organ tablature

- trumpeter, keyboard

player, lutist equally

found their way through

this simple,

amateur-level tablature

script. To be sure, each

played of it what he

could: the trumpeter

played only the melody,

the bass played only the

bass part; for the

collection is put down

in two parts. The lutist

would fill out these two

extremities with inner

chords, occasionally

adding appropriate

figurations.

You will also meet the

names of some of the

giants of the lute: the

Hungarian Bakfark,

Newsidler, who also came

from Hungarian soil;

Dowland, who flourished

half century later; from

Italy, the “divine”

Francesco da Milano. We

are naturally tempted to

compare their

activities. All four

composers ranked among

the greatest of their

age: playing at royal

courts, they were

composers and performers

at the same time, but

may have done political

services, too, at one

time or another. Balint

Bakfark, a Hungarian by

birth, turned up at

nearly every European

court. He was born in

Transylvania, became the

lutist of Buda Castle,

then went on through

Italy to Lyon, where his

first lute book was

published (Intabulatura

1553). Later he moved to

Poland where he worked

for 17 years; but he had

to flee because of some

intrigue, nearly losing

his life in the flight.

He went to Vienna right

away and for a while

served as court lutist

to Emperor Maximilian;

at last he settled in

Italy, at Padua, where

he taught compositionasa

university professor.

Some hint as to his

teaching method can be

gathered from a letter

in which a student of

his complains to his

patron: “Maestro Bakfark

is an excellent teacher,

but I wish I did not

have to sleep under his

roof: for it is all

right to teach during

the day, but he often

wakes me from my sleep

and beats me till I play

as is pleasing to him.“

(Actually, this lutist

did learn his craft

well, for he became

court musician in

Prussia.)

Bakfark was a typical

Renaissance personality,

whose virtuosity was

sung by contemporary

poets. To quote just one

example: the great

Polish humanist poet Jan

Kochanowski wrote:

“Touch not the lute

after Bakfark!” I

included in the present

recording two

intabulations and an

original fantasy.

Bakfark’s intabulation

technique is as simple

as can be: he plays on

his instrument exactly

what the choir composer

wrote for 4 or 5 or 6

parts. Indeed, this

sounds almost too simple

- but it isn’t.

Intabulators usually

distorted the piece;

reducing the chords to

inversions different

from those in the

original, in order to

simplify and, as it

were, instrumentalize

them. The problem with

Bakfark is that he

writes down exactly what

he sees or hears. The

left hand will

consequently have to

play tortuous

arrangements, the piece

will bear little

affinity to the

instrument - but the

result speaks foritself!

He applies little

figuration in the two

intabulations, but where

he does, and the way he

weaves them into the

piece, they are

unalterable. This is why

one uses less figuration

in Bakfark than

elsewhere: one would

lose rather than gain

byit. Nine original

compositions by Bakfark

are extant. He has nine

fantasies; the tenth,

also bearing the name

fantasy, is a

transcription. Fantasy

1” has a motet-like

structure, with

non-returning themes; it

launches new themes in a

fourpart fugue-like

manner. As the

respective themes are

completely separated and

express different

atmospheres, I thought

to give each of them a

different character

bothin dynamics and in

tempo, even though there

is no indication to this

in the notation - but

one may take this amount

of liberty with a

fantasy.

Italian lute music is

represented on the

record by Francesco da

Milano and Joan Ambrosio

Dalza. Francesco, like

Bakfark, moved about in

the biggest courts, and

penned innumerable

fantasies, which count

as the greatest in that

genre. A direct road

leads from Francesco’s

fantasies to the

variations of

Frescobaldi and Bach. I

have chosena ricercare,

more harmonic in

character but likewise

ornamented with

contrapuntal insets.

Dalza is one of the

first lutists ofthe 16th

century; one year after

the appearance of the

firstever printed lute

book (Francesco

Spinaccino: Intabolature

1507), he publishes his

own collection of

dances: surprisingly

early “suites”, series

of several movements

mostly elaborating one

theme. Here the Pavane

is followed by the

Saltarello and the

bagpipe-like Piva.

Especially in the Piva

movement we have an

obvious case of folk

music adaption. The

dances have a

sophisticated asymmetry

- each time I play them

again, they strike me

with their novelty.

J. A. Dalza’s tunes,

then, are the earliest

pieces on our record;

the latest ones are

Elizabethan dances from

England. Dowland,

Cutting and Bulman are

among the greatest from

this âge, but so many

lutists, instrumental

and vocal composers are

active in this period

that we shall not

attempt to list them.

After the defeat of the

great Spanish Armada

England emerges as the

greatest economic and

military power of

Europe, with a rich

middle class: this

evidently had its effect

on the musical scene,

too. Dozens of printers

set up, and there was

music everywhere, from the

simplest townhouse to

the most luxurious

palace. We even have

etchings showing a

barber’s shop with

musical instruments on

the wall: those waiting

for their turn would not

gossip or discuss

politics or, as

nowadays, leaf through

funny or sex magazines,

but play music, each

taking his part.

The most significant

master is undoubtedly

John Dowland, a

controversial, truly

renaissance figure, who,

similarly to Bakfark,

went through all sorts

of personal intrigues

and whose life abounds

in surprising turns. The

lute pieces of

Elizabethan composers

could be played on

orpharion or bandora as

well. I play the English

lute pieces onan

orpharion: a Biffin,

made in Australia in

1971. I chose it, with

its metallic ringing,

for the sake of greater

variety. (See picture

No. 1.)

There remain the works

of the German

Newsidlers: the “Fugger

Tanz” by Melchior, and

the profane dances by

Hans. Profane they are

indeed, and vulgar too,

especially the

Gassenhauer, very much

like today’s pub music.

If we compared the

dances of Dowland and

Waissel to today’s pop

music, we may certainly

compare the Newsidlers’

Gassenhauer to today’s

pub or “Schrammel”

music.

So, I have tried to

present a century’s

secular lute musicin a

selection that would

best characterize the

age, including everything

from vulgar to dance,

courtly and folk dance

music up to the most

complicated fantasy.

The instrument I play on

is a replica of the 1641

lute of Matteo Sellas

alla corone in Venetia.

(Its original is in the

Hungarian National

Museum. Cote 1951.43.

Delhaes 1902.20.) (See

cover photo.)

Daniel

Benkö

Notes:

1.) Matthaus Waissel:

Tablatura, 1573. mod.

ed. Orpheus. Editio

Musica, Budapest, 1980.

ed. by Daniel Benkò.

2.) Balint Bakfark:

Intabulatura 1553, mod.

ed. Opera Omnia, Editio

Musica, Budapest, 1976.

ed. by Istvan Homolya

and Daniel Benkö.

|

|