|

| 1 CD -

8.44012 ZS - (c) 1988 |

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9522-A - (p) 1968

|

|

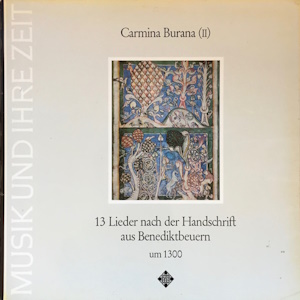

CARMINA BURANA (II) - 13 Lieder

nach der Handschrift aus Benediktbeurn

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Homo quo vigeas,

C.B. No. 22 - Mezzosopran, 3 Tenöre,

Baß, Posaune

|

|

1' 22" |

1 |

A1

|

| Walther von Châtillon

|

Ecce torpet,

C.B. No. 3 - Baß, Organetto,

Fidel, Laute, Tambourin, Schellen |

|

6' 35" |

2 |

A2

|

|

Licet eger cum

egrotis, C.B. No. 8 - Tenor,

rebab |

|

4' 32" |

3 |

A3

|

Peter von Blois

|

Vite

perdite, C.B. No. 31 (Peter

von Blois) - Mezzosopran,

Countertenor, 3 Tenöre, Baß, Rebec,

2 Tambourins |

|

3' 35" |

4 |

A4

|

|

Crucifigat

omnes, C.B. No. 47 -

Mezzosopran, Countertenor, 3

Tenöre, Baß |

|

2' 55" |

5 |

A5

|

|

O varium

Fortuna, C.B. No. 14 -

Mezzosopran, Tenor |

|

4' 00" |

6 |

A6

|

|

Celum non animum,

C.B. No. 15 - Mezzosopran, 2 Tenöre |

|

4' 05" |

7 |

B1

|

| Peter von Blois |

Dum

iuventus, C.B. No. 30 (Peter

von Blois) - Tenor, Laute, Fidel

|

|

3' 10" |

8 |

B2 |

|

Axe

Phebus aureo, C.B. No. 71 -

Mezzosopran, Rebec, Laute |

|

2' 45" |

9 |

B3 |

|

Ecce

gratum, C.B. No. 143 - Tenor,

Laute, Fidel, Organetto, Schellen,

Tambourin |

|

2' 58" |

10 |

B4 |

|

Tellus flore,

C.B. No. 146 - Countertenor,

Citôle |

|

2' 25" |

11 |

B5 |

|

Tempus est

iocundum, C.B. No. 179 -

Mezzosopran, Rebec, Citôle |

|

3' 12" |

12 |

B6 |

Neidhardt von

Reuenthal

|

Nu gruonet aver

diu heide, C.B. No. 168a

(Neidhardt von Reuenthal) - Tenor,

Harfe, Psalterium, Rebab |

|

3' 28" |

13 |

B7 |

|

|

|

|

|

| STUDIO

DER FRÜHEN MUSIK |

Quellen:

|

-

Andrea von Ramm, Mezzosopran,

Harfe, Organetto

|

- Cambridge,

University Library Ff I-17

|

-

Willard Cobb, Tenor,

Tambourin

|

- Erfurt,

Staatsbibliothek Amplon. Oct. 32

|

-

Sterling Jones, Rebec,

Fidel, Rebab

|

- Florenz, Bibl.

Laurenziana, Pluteus 29. I. |

| -

Thomas Binkley, Posaune,

Laute, Tambourin, Citôle,

Psalterium |

- München, Bayr.

Staatsbibliothek, Codex Buranus

cm. 4660 (= Carmina Burana)

|

| Weitere

Mitwirkende: |

|

| -

Grayston Burgess, Countertenor |

|

| -

Nigel Rogers, Tenor,

Schellen, Tambourin |

|

-

Desmond Clayton, Tenor

|

|

| -

Jacques Villisech, Baß |

|

| -

Horst Huber, Schlaginstrumente |

|

| Thomas

BINKLEY, Übertragung und

Bearbeitung |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Amsterdam

(Holland) - Oktober 1967

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf

Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken

- SAWT 9522-A - (1 LP) - durata

45' 23" - (p) 1968 - Analogico

|

|

|

Edizione

"Reference" CD

|

|

Tedec

- 8.44012 ZS - (1 CD) - LC 3706 -

durata 45' 23" - (c) 1988 - AAD |

|

|

Cover |

|

"Musizierende

Kinder", Porzellan. Modell von M.

V. Acier, Meißen, um 1770. Museum

für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg.

|

|

|

|

|

Among the

most valuable treasures

of the Bavarian State

Library in Munich is

Codex latinus monacensis

4660, comprising the

most comprehensive and

most important

collection of secular

Latin lyrics of the

Middle Ages (often

erroneously generalized

under the expression

"Goliardic song"), the Carmina

Burana.

Before being moved to

the Royal Court and

Central Library during

the secularisation of

Bavarian Monasteries in

1803, the manuscript was

kept in the

Benediktbeuren

Monastery; hence this

collection of poetry was

named by its first

editor, the librarian

Johannes Andreas

Schmeller, "Songs from

Benediktbeuren".

When the manuscript was

written, after the

moddle of the 13th

century, somewhere in

South Germany (or

Tyrol?), the flowering

of secular Latin poetry

was already over. Thus

the collection is not a

textbook of a Goliard

but an anthology written

on the order probably of

a clerical aristocrat

who enjoyed this poetry.

The manuscript can be

compared in kind to the

large collections of

middle-high German

poetry such as the

Manesse manuscript.

The manuscript brings

together over 200 pieces

of differing content and

character. The order of

the pieces (disrupted

through binding) was

carefully planned

according to four main

groups: moral and

satirical songs

(observations and

laments on the course of

the world or the

lowering of morals, love

songs, drinking songs,

game songs and real

Goliardie poetry (no

neumes preserved), and

sacred plays. poems of

subjective sensitivity

are found sext to poems

of didactic or learned

character. The greatest

portion sterms from the

late 11th and the 12th

centuries; the majority

of the poetry originated

in France. a few German

poems are mixed in with

the Latin ones. As was

the custom in such

anthologies, the poets

were not named, almost

without exceptions;

however many poems are

lnown through other

soucers, and we can thus

recognize the work of

few known poets as

Walther de Chatillon,

Petrous de Blois, the

archipoeta, etc., while

other poems can be

arranged in groups. The

concordant sources of

single poems are

particularly important

for the reconstruction

of the original texts;

in codex Buranus the

texts are often corrupt.

It seems that the

inclusion of neumes had

been planned for much of

the manuscripts, but

this was carried out for

only a small part, and

there only afterwards

and rather incompletely.

F.

Brunhölzl

The production in 1965

of the recording Carmina

Burana aus der

Originalhandschrift

(Teldec SAWT 9455-A) was

the first attempt to

enter the distant realm

of medieval Latin lyrics

in their original

musical settings. The

recording was an

immediate success, and

was winning prizes. The

performance style

clearly shows the

influence of Spanish

arab culture on Western

musical practice. Now,

after three years of

further research and

publication, this

emphasis seems

completely confirmed.

The present recording

not only delves further

in that direction but

also calls attention to

another important and

neglected aspect of the

musical practice of

pre-Fourteenth century

Europe: the

non-homogeneity of

regional sayles. The

manuscript Carmina

Burana in an

excellent choice of

subject because it is a

collection of European

poetry predominantly in

Latin, collected long

after the poetry itself

had been disseminated

throughout Europe. This

repertory was indeed

international and

interregional, and yet

its performance was

bound to regional

performance styles. It

is important to state

that this repertory was

regional by intent,

except in rare cases

such as C.B. No. 47, but

was destined to become

international quite by

natural processes. Our

sources for concordances

with the Carmina

Burana manuscript

extend over several

countries, including

England, France,

Germany, Italy and

Spain. We must insist

that the performance

given a random selection

of this repertory in the

provincial Alpine

Monastery of

Benediktbeuren in the

Thirteenth century,

where the manuscript was

copied, differed very

considerably from a

performance of that same

sampling in Córdoba or

Sevilla, major cultural

centers in which a

Christian minority lived

and studied alongside

the Sepharic and

(dominant) arabic

civilizations. Thus a

monophonic sequence may

have had a ritual choral

performance tradition in

St. Gall, the monks

singing to themselves

about themselves near

the center of the

Christian sphere of

influence, whereas in

Badejoz it becomes a

solo song, carrying a

message to the insecure

far outpost of

Christianity, where ad

educated man still

practiced his vernacular

employing the Arabic

alphabet. To a large

extent, the

differentiated styles of

regional performance are

documented in musical

sources, by commentary

of travellers and by

theoreticians

(especially Juan Gill's

Ars musice

written in Zamora about

this time, 1254, of the

establishment at

Salamanca of the first

university chair in

music in all of Europe).

We see the regional

performance styles as a

product of the degree of

exotic influence in that

region. During the early

period, the major

cultural center was

Córdoba, later Paris.

Distance from these and

other centers determined

to a great extent the

influence of these

centers of serious art

of the regions. Thus the

style known as

"Provençal" was able to

remain intact, being the

node between the arabic

South and the French

North. England and

Germany retained a

relatively isolated

character, while Spain

and Italy underwent

nearly constant change

of cultural equilibrium.

The two major poles were

the traditional

inherited performance

styles indigenous to the

area and the imported

and superimposed Arabic

style either as it was

introduced before the

nineth century, or as it

developed in Europe

during the following

centuries. The classical

form of the late

Andalusian style is

contained in the concept

of the "nuba", in the

idea of a complete

performance with several

parts including an

instrumental

improvisation without

rhythm, followed

immediately by one with

rhythm, then the

introduction of song

(after the attention of

the audience has been

attracted), then a

change of rhuthm with

more instrumental music,

then song again, etc.,

until the conclusion

(Ecce gratum). Opposed

to this style was a more

direcs, less organized

song-cum-accompaniment

style of the Germanic

countries (Dum iuventus

floruit).

We have discussed the

transcriptions, the

instruments and the

accompaniments

elsewhere, and invite

the reader to consult

the following:

- Minnesang und

Spruchdichtung, SAWT

9487-A

- Weltliche Musik um

1300, SAWT 9504-A

- Carmina Burana (I),

SAWT 9455-A

Thomas

Binkley

|

|