|

|

1 CD -

SK 62 824 - (p) 1997

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Piano Concertos Nos. 3

& 4 |

|

69' 09" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van BEETHOVEN

(1770-1827) |

|

|

|

| Concerto

for Piano & Orchestra No. 3 in C

minor, Op. 37 |

|

35' 59" |

|

| - Allegro con brio |

17' 10" |

|

1

|

| -

Largo |

9' 25" |

|

2

|

| -

Rondo. Allegro |

9' 24" |

|

3

|

| Concerto

for Piano & Orchestra No. 4 in F

major, Op. 58 |

|

32'

05"

|

|

| -

Allegro moderato |

18' 50" |

|

4

|

| -

Andante con moto |

3' 55" |

|

5

|

| -

Rondo. Vivace |

10' 10" |

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

Jos

van Immerseel, pianoforte

(Hammerflügel)

|

Tafelmusik

on period instruments |

|

| Cadenzas: Ludwig

van Beethoven |

Jeanne Lamon, music

director |

|

|

Bruno

Weil, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kloster

Benediktbeuern /Germany) - 12/14

September 1996 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Tape Editor /

Mastering |

|

Stephan

Schellmann |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 62 824 - (1 CD) -

durata 69' 09" - (p) 1997 - DDD |

|

|

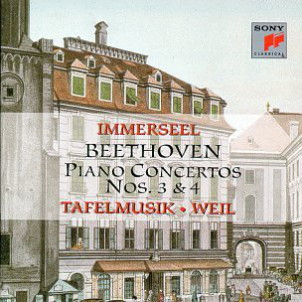

Cover Art

|

|

Der

Michaelplatz gegen die K. K.

Reitschule (1783) by Carl

Schütz (1745-1800), Vienna,

Historisches Museum |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Beethoven

was often rather off-hand

about his earlier works.

Offering the new C-minor

Concerto (No. 3, Op. 37) to

Breitkopf & Härtel, he

spoke rather disparagingly

about the two earlier works.

While he perhaps deliberately

exaggerated the situation for

commercial reasons, there is

no doubt that the

“out-Mozarting" trend here

reaches its height. The model

was, quite obviously, Mozart`s

great and stirring Concerto in

C minor, K. 491, which we know

Beethoven much admired. (“Ah,

Cramer," he said to the

visiting British pianist when

both were listening to the end

of K. 491, "we'll never be

able to do anything like

that.”) In a sense, Beethoven

does push the gaunt and yet

(in the slow movement)

tenderly loving music of K.

491 a step further in Op. 37.

It was the culmination of his

efforts to be an

over-life-size Haydn and

Mozart combined.

This concerto has (or rather,

had) a chronological problem.

It was maintained before the

Second World War, and even

later, that the autograph

manuscript (now in the

Deutsche Staatsbibliothek,

Berlin) was dated “Concerto

1800 Da L. v. Beethoven,” and

it was described as such in

the definitive catalog of

Beethoven's music, Das

Werk Beethovens: Thematisch

bibliographisches

Verzeíchnís seiner

sämtlichen vollendeten

Kompositíonen, by Georg

Kinsky (Henle Verlag, Munich

1955, p. 92). But this

manuscript was then lost: it

had in fact been evacuated for

safe-keeping during the Second

World War from Berlin to a

monastery at Grüssau in

Silesia (now Krzeszów in

Poland) and, after a series of

adventures, was finally

returned to the Berlin Library

in 1977. And great was

everyoneßs astonishment when,

upon examination, it was seen

that the date on the

manuscript was not 1800 but

1803. Previously it had been

assumed that Beethoven first

performed the work at the

benefit concert which the

composer gave in the Vienna

Burgtheater in April 1800. But

this could now no longer be

maintained, since the work was

not completed until three

years later; indeed, according

to the manuscript's

watermarks, the autograph

might even date from slightly

before 1803.And the whole

problem is rendered more

complicated by the arrival of

a new piano from Paris.

The Third Concerto was

possibly begun in 1800,

probably shortly before the

April benefit concert, but not

completed until 1803, after

the arrival of a new Erard

pianoforte from Paris. (This

firm delivered one to Beethoven

and one to Prince Lichnowsky -

both have survived.) The

technical innovations and the

enlarged keyboard of the new

Erard were immediately

utilized in the C minor

Concerto, the first

performance of which was at

the concert of April 5, 1803,

which featured the oratorio Christ

on the Mount of Olives

and the Second Symphony. The

following year Beethovenßs

pupil Ferdinand Ries played

the concerto with the composer

conducting. The Allgemeine

Musikalische Zeitung

thought that Op. 37 “without

doubt belongs among

Beethoven's most beautiful

compositions. It is worked out

in a masterly fashion”

With the Fourth

Concerto in G major, Op.

58, we move into a

world far removed from that of

the first three: if the spirit

of Mozart hovered over the

earlier concertos, with No. 4

we are in the middle of

Beethovenßs own spiritual

domain: tender, poetic,

forceful, humnrous. For many

people this is the most

perfect, most personal, most

tender of all Beethoven's

piano concertos. Like Mozart's

K. 271, the piano opens the

work all by itself, and the

orchestra reveals itself

coyly, like a young maiden,

until we realize that it is

indeed a grand orchestra, even

to trumpets and drums, which,

dramatically, do not enter

until the finale. The rhapsodic

slow movement is in the great

tradition of an instrument

pretending to be a human voice

- the recitatívo

accompagnato that was to

figure so effectively in the

Ninth Symphony's finale. The

first public performance of the

Fourth Concerto took place,

with Beethoven as soloist, at

a concert in the Theater an

der Wien on December 22, 1808,

which also included the

premières of the Fifth

and“Pastoral” Symphonies and

the Choral Fantasia.

We have two horrendous

descriptions of this

catastrophic concert, one by

Ferdinand Ries and one by the

German composer and writer on

music Johann Friedrich

Reichardt.

“Beethoven gave [writes Ries]

a large concert in the Theater

an der Wien, at which were

performed for the first time

the C minor and "Pastoral"

[...] Symphonies as well as

his Fantasia for Piano

with orchestra and chorus. In

this last work, at the place

where the last beguiling theme

appears already in a varied

form, the clarinet player

made, by mistake, a repeat of

eight bars. Since only a few

instruments were playing, this

error was all the more evident

to the ear. Beethoven leapt up

in a fury, turned around and

abused the orchestral players

in the coarsest terms and so

loudly that he could be heard

throughout the auditorium.

Finally, he shouted,`From the

beginning!' The theme began

again, everyone came in

properly, and the success was

great. But when the concert

was finished, the artists,

remembering only too well the

honorable titles which

Beethoven had bestowed on them

in public, fell into a great

rage, as if the offense had

just occurred. They swore that

they would never play again if

Beethoven were in the

orchestra, and so forth. This

went on until Beethoven had

composed something new, and

then their curiosity got the

better of their anger [...].”

“During the past week, [writes

Reichardt] when the theatres

were closed and the evenings

were taken up with musical

performances and concerts, my

eagerness and resolution to

hear everything caused me no

small embarrassment. This was

particularly the case on the

22nd, because the local

musicians gave the first of

the season's great musical

performances in the

Burgtheater for the benefit of

their admirable Society for

Musicians` Widows; on the same

day, however, Beethoven also

gave a concert for his own

benefit in the large suburban

theatre, consisting entirely

of his own compositions. I

could not possibly miss this

and at midday accepted with

heartfelt gratitude Prince

Lobkowitz's kind invitation to

take me with him in his box.

There we held out in the

bitterest cold from half past

six until half past ten, and

experienced the fact that one

can easily have too much of a

good - and even more of a

strong - thing. I, no more

than the extremely kindly and

gentle Prince, whose box was

in the first tier very near to

the stage, on which the

orchestra, with Beethoven

conducting, were quite close

to us, would ever have thought

of leaving the box before the

very end of the concert,

although several faulty

performances tried our

patience to the utmost. Poor

Beethoven, for whom this

concert provided the first and

only genuine profit that he

had been able to earn and

retain during this whole year,

had encountered a great deal

of opposition and very little

support both in its

organization and performance.

The singers and the orchestra

were assembled from very

heterogeneous elements.

Moreover, it had not even been

possible to arrange a complete

rehearsal of all the pieces to

be performed, every one of

which was filled with passages

of the utniost difficulty. You

will be amazed [to hear that]

all this was performed by this

fertile genius and untiring

worker in the course of four

hours."

©

1997 H.C. Robbins Landon

|

|

|