|

|

1 CD -

SK 63 365 - (p) 1998

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Piano Concertos No. 5 -

Violin Concerto |

|

71' 55" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van BEETHOVEN

(1770-1827) |

|

|

|

| Concerto

for Piano & Orchestra No. 5 in E

flat major, Op. 73 "Emperor" |

|

35' 48" |

|

| - Allegro |

19' 30" |

|

1

|

| -

Adagio un poco moto |

6' 43" |

|

2

|

| -

Rondo. Allegro |

9' 35" |

|

3

|

Concerto

for Violin & Orchestra in D major,

Op. 61 *

|

|

35'

53"

|

|

| -

Allegro ma non troppo |

19' 56" |

|

4

|

| -

Larghetto |

7' 11" |

|

5

|

| -

Rondo.Allegro |

8' 46" |

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

Jos

van Immerseel, fortepiano

(Tröndlin, early 19th century)

|

Tafelmusik

on period instruments |

|

Vera

Beths, violin

(A. Stradivarius, Cremona, 1727)

|

Jeanne Lamon, music

director |

|

| Cadenzas:

Anner Bylsma * |

Bruno

Weil, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kursaal,

Bad Tölz (Germany) - 8/10

september 1997 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Tape Editor /

Mastering |

|

Stephan

Schellmann |

|

|

Art Direction |

|

Benita

Raphan |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 63 365 - (1 CD) -

durata 71' 55" - (p) 1998 - DDD |

|

|

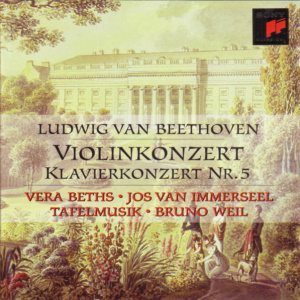

Cover Art

|

|

Palais

Rasumofsky, Wien (ca.1815)

by Louis v. Montoyer; Vienna,

Historisches Museum, Courtesy:

AKG, Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Beethoven

completed five piano concertos,

which nowadays count among his

most frequently played and

best-loved works for keyboard.

This great series was

concluded by the martial,

stunning E flat concerto that

Anglo-Saxon audiences have

termed the “Emperor.” The

Fifth Concerto was composed as

the French were

bombardingVienna in May

1809.There is no record of its

first Viennese performance -

if, indeed, it had one in the

chaotic aftermath of the

French occupation. The first

edition was brought out by

Muzio Clementi in London.

Dedicated to Archduke Rudolph

- the recipient of more great

pieces of music than anyone

else in history - the“Emperor”

Concerto is a unique blend of

brilliant piano writing,

spacious orchestration, formal

perfection and interesting

thematic material developed

with great intellectual

prowess.

Although Op. 73 officially ends

this series, Beethoven had by

no means given up the idea of

writing piano concertos. There

are extensive sketches for a

concerto that the composer

intended to write around 1816.

We do not know why he gave up

the idea, but it is a sad

thought that if only one of

his publishers had forced the

issue (and perhaps sealed it

with a case of wine) we should

have had what, from the

sketches,would appear to have

been a magnificent, large-scale

sixth concerto.

We may fondly imagine that

Beethoven`s five piano

concertos have always formed

the cornerstone of the form,

together with Mozart's mature

piano concertos. Yet those who

have studied the autobiography

of the great pianist Artur

Schnabel will know that in

Vienna at the turn of the

century this was not the case

at all. When Schnabel made his

debut at the age of eight, he

“played the D Minor concerto

by Mozart, still considered a

work accessible chiefly to

children - traditional

misconceptions of this sort

have an astonishing

longevity.” And if this

statement sounds

extraordinary, consider the

following: “During my

educational phase in Vienna

until 1899, I never heard, in

this most musical city on

earth, and in the midst of

musicians, of the existence of

the twenty-eight Concertos by

Mozart, or Beethoven's Opus

106 or the Diabelli

Variations, or Bach's Goldberg

Variations, etc. The G

major Concerto by Beethoven

was generally labelled, among

musicians, as the"ladies"

concerto. Hardly any of the

great pianists ever played it.

The C minor was only played in

conservatories by the lower

grades and the C major

Concerto only by the

debutantes. The B flat major

Concerto was simply unknown.”

We have come to think of

Beethoven as the one composer

who always survived the

vicissitudes of fluctuating

taste, but, as Schnabel

reminds us, even this is one

of music history's many

fallacies.

One of Beethoven's colleagues

and friends was the violinist

Franz Clement, who had been a

child prodigy, playing solo in

the Haydn/Solomon concerts in

London (1791) and also making

a successful tour of Europe.

In 1806, Beethoven wrote his

only violin concerto for

Clement, who gave the first

performance in the Theater an

der Wien, where he was leader

of the orchestra, on December

23, 1806 at his benefit

concert. A contemporary report

(Johann Nepomuk Möser) tells

us of the work`s favorable

reception: “The excellent

violinist Clement also played,

besides other beautiful

pieces, a Violin Concerto by

Beethhofen [sic] ,

which on account of its

originality and many beautiful

parts was received with

exceptional applause.

Clement's genuine art and

gracefulness, his power and

assurance on the violin -

which is his slave - called

forth the loudest bravos. As

regards Beethhofen's Concerto,

the verdict of the experts is

unanimous, allowing it many

beauties, but recognizing that

its scheme often seems

confused and that the unending

repetitions of certain

commonplace parts could easily

prove wearisome... This

Concerto was generally well

liked, and Clement's cadenzas

exceptionally well received."

Meanwhile, the famous

composer, Muzio Clementi, now

part-owner of an English

publishing house, came to

Vienna and wanted to engage

Beethoven for his firm. His

attempts, which were

successful, are detailed in

the following amusing letter

(written in English):

Messrs.

Clementi & Co.,

No. 26

Cheapside,

London.

Vienna, April 22nd, 1807

Dear

Collard:

By a

little management and

without committing myself,

I have at list made a

compleat conquest of that

haughty beauty,

Beethoven, who first began

at public places to grin

and coquet with rne, which

of course I took care not

to discourage; then slid

into familiar chat, till

meeting him by chance one

day in the street - “Where

doyou lodge?” says he; “I

have not seen you this long

while!" - upon which I

gave him my address. Two

days after I found on my

table his card brought by

himself, from the maid's

description of his lovely

form. This will do,

thought I. Three days

after that he calls again,

and finds me at home.

Conceive then the mutual

ecstasy of such a meeting!

I took pretty good care to

improve it to our house's

advantage, therefore, as

soon as decency would

allow, after praising very

handsomely some of his

compositions: “Are you

engaged with any publisher

in London?” - “No” says

he. “Suppose, then, that

you prefer me?” - “With

all my heart.”

“Done. What have you

ready?” - “I'll bring you

a list.” In short I agreed

with him to take in mss.

three quartets, a

syrnphony, an overture and

a concerto for the violin,

which is beautiful, and

which, at my request he

will adapt for pianoforte

with and without

additional keys; and a

concerto for the

pianoforte, for all which

we are to pay him two

hundred pounds sterling.

The property, however, is

only for the British

Domínions. To-day sets off

a courier for London

through Russia, and he

will bring over to you two

of the three mentioned

articles.

Remember

that the violin concerto

he will adapt hirnselƒand

send it as soon as he can.

As a result of

their meeting, Beethoven

rewrote the Violin Concerto

for piano, adding a remarkable

cadenza in the first movement

for piano and timpani, and

dedicating the arrangement to

the wife of his old friend

Stephan von Breuning, Julie

(née von Vering).

The Violin Concerto became a

model for the budding Romantic

violin concerto, particularly

the rhapsodic slow movement.

The opening movement shows a

remarkable application of a

single motif - in this case,

announced by five identical

notes on the timpani - for

large sections of the music.

The opening octaves of the

solo part have become a

tcxtbook case requiring

flawless bowing and finger-work

if it is to arrive in tune.

The rhythmically taut and

energetic finale shows a side

of Beethoven that we sometimes

tend to overlook - optimistic,

full of confidence and with a

matchless sense of formal

symmetry.

©

1998 H.C. Robbins London

|

|

|