|

|

1 CD -

SK 53 341 - (p) 1993

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Codex Las Huelgas - Music

from 13th century Spain |

|

55' 59" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Es

illustri nata prosapia (Conductus

Motet) - Folio 119 verso - 120 recto |

5' 32" |

|

1

|

| Crucifigat

omnes (Conductus) - Folio

97 verso - 97 recto |

3' 07" |

|

2

|

| O

Maria maris stella (Motet) - Folio

102 verso - 103 recto - 124 recto

- 124 verso - 125 verso |

4' 15" |

|

3

|

| Ex

agone sanguinis (Conductus) -

Folio 61 verso - 62 recto - 62

verso |

2' 20" |

|

4

|

| Belial

vocatur (Conductus Motet) - Folio

82 recto - 82 verso - 83 recto |

5' 36" |

|

5

|

| Sanctus

- Folio 16 verso - 17 recto |

4' 59" |

|

6

|

| Agnus Dei -

Folio 21 recto |

3' 59" |

|

7

|

| Benedicamus

Domino - Folio 25 verso

- 26 recto |

2' 00" |

|

8

|

| Flavit

auster - Folio 45 recto -

45 verso - 46 recto - 46 verso |

4' 19" |

|

9

|

| Eya

mater - Folio 46 verso -

47 recto - 47 verso - 48 recto |

7' 15" |

|

10

|

| Quis

dabit capiti (Prosa) - Folio

159 recto |

3' 35" |

|

11

|

| Casta catholica

(Conductus Motet) - Folio 121

verso - 122 recto |

4' 34" |

|

12

|

| Homo

miserabilis (Motet) - Folio

127 verso - 128 recto |

3' 27" |

|

13

|

|

|

|

|

| Huelgas

Ensemble |

|

| Paul

van Nevel, conductor

& all transcriptions |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Chapel

of Cistercian Abdij Marienlof

(Belgium) - 9/11 October 1992 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording engineer

/ editing

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 53 341 - (1 CD) -

durata 55' 59" - (p) 1993 - DDD |

|

|

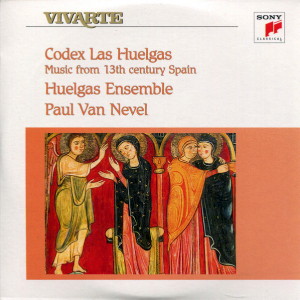

Cover Art

|

|

Altar

frontal from Avia - Museu

Nacional d'Art de Catalunya |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

In

1098 a new monastic order was

founded in a monastery not far

from Dijon. The new movement

wanted to return to a monastic

way of life which was based

upon the strict rules of the

Benedictine order; it

established itself first at

Citeaux. The name of the order

was derived from the Latin

name of the abbey, Cistercium;

it was known as the Cistercian

order.

The movement soon flourished,

and towards the end of the

12th century there were over

500 Cistercian monasteries and

establishments all over

Europe.

The Cistercian order advocated

more simplicity and a less

elaborate liturgy and demanded

more physical work from its

members. This simplicity also

had an effect on Cistercian

art. In architecture, for

example, strict rules were

applied in which Gothic lines,

use alone and without much

ornamentation, created a quiet

impression in a building. In

the decorative arts, too - for

example in book illustrations

- all superfluousness was

avoided.

This tendency can also be

established in the field of

music. As early as the 12th

century the Cistercians were

searching for the original

melodies of Gregorian chant.

Monks were sent to Metz to

copy the Antiphonarium

gregorianum. Then this

work was corrected and

simplified according to the

rules of the handbook written

in 1140, Epistola seu

tractatus de cantu seu de

correctione Antiphonarii.

Melismas were shortened,

repeats omitted, authentic and

plagal modes clearly

distinguished from one

another. In addition all

melodies were kept within a

range of 10 notes (in

psalterio decachordo psallam

tibi).

In the course of the 13th and

14th centuries, however, the

idea of simplicity gradually

retreated into the background,

as often happens with trends,

the ideas of which become

watered-down to the same

extent as they spread

spatially and temporally and

become removed from their

original source. This was also

to be the case with the

architecture and music of the

monastery of Las Huelgas.

The first convent of the

Cistercian order was founded

in 1125 at Tart (in the

diocese of Langres). This did

not happen, however, without

conflict: The male branch of

the order was at first opposed

to the expansion, for many

convents achieved their own

jurisdiction and led an

independent existence.

More than 50 years after the

founding at Tart, one of the

most famous Cistercian

convents came into being in

the Burgos region of Spain:

the Real Monasterio de Las

Huelgas. King Alfonso VIII of

Castile built the convent in

1187 as a kind of Pantheon for

the Castilian royal house.

Kings were crowned and buried

here, and peace treaties

signed. Above all an abbey

community lived here,

consisting of sisters, girls

of noble birth, who were

directed by the nuns, a Schola

cantorum and a Scriptorium.

And soon the ideal of

simplicity was abandoned

again; under King Alfonso el

Sabio (1226-1284) Las Huelgas

developed into a cultural

centre in which Jewish

scholars and Mudejars

(Moslems under Christian

jurisdiction) lived with the

Catholic population of the

abbey under one roof. This

cultural diversity also left

its mark on the architectural

style of the convent. Thus the

eight-sided dome of the

presbytery is identical with

the dome of a minaret of the

Kutubija mosque in Marrakesh;

the Chapel of San Salvador in

the convent is decorated with

Mudejar inscriptions.

Under King Alfonso el Sabio

music flourished here too. In

this convent one of the last

music manuscripts from the Ars

antiqua of the 13th century

was written: the so-called

Codex Las Huelgas.

This manuscript is unique for

various reasons. Firstly, the

Codex Las Huelgas is the only

music manuscript of its time

which is still at its place of

origin: it was written in Las

Huelgas and is kept there

today. Further, this

collection allows in every

respect a kaleidoscopic

insight into the music of the

Ars antiqua: it contains not

only the “Evergreens” of the

Paris Notre Dame school ( e.

g. O Maria maris stella)

but also Spanish compositions

of local significance and works

which were specially written

for Las Huelgas. The Codex Las

Huelgas contains many pieces

of music which are not to be

found in any other manuscript

in the world. The repertoire

extends from the end of the

12th to the beginning of the

14th century, with the

emphasis placed on the music

of the second half of the 13th

century - it is no coincidence

that this was the period in

which King Alfonso el Sabio

reigned.

The comprehensive manuscript

(170 folios) contains more

than 180 liturgical and other

sacred works, among them 141

polyphonic compositions. All

forms and styles are

represented: sections of the

Mass (often as a trope, i. e.

with interpolated text),

conductus in one and more

parts, Latin motets,

sequences, settings of the Benedicamus

domino, prosa (mostly

strophic, such as Eya

mater), Alleluias,

laments (planctus), even

exercises in solmisation. All

these works are scored for 1

to 4 voices, although the more

usual two and three-part

settings predominate.

The notation of most of the

works displays a manifold use

of ornaments. This is an

aspect which to the present

day has received too little

attention. The Huelgas

Ensemble attempts in this

recording to integrate the

longforgotten art of

ornamentation into the

compositions of the Ars

antiqua - but there will be

more about that later.

The works on this recording

Ex illustri is a

conductus motet. Although the

metre of the voices is

regular, as is the case in

most conductus pieces in

several parts, two of the

voices have differing texts,

and that again gives the motet

its character. The work

displays another remarkable

feature: as a great exception

to the rule the rhythm here is

binary, whereas the six

rhythmic modes of the Ars

antiqua are all ternary. Both

texts are songs of praise to

Saint Catherine (4th century),

referring to her mystic

marriage and her dreadful

martyrdom.

Casta catholica

is also a conductus with two

text, which, in contrast to Ex

illustri, are subjected

to considerable melismatic

treatment. In addition hocket

figures are used. The text

refers to Doña Maréa Gonaáles,

Abbess in Las Huelgas from

1286 till 1313.

Crucifigat omnes

was a very well-known

conductus, which is to be

found at five further sources.

It is a militant Crusade song,

which has survived in the

Codex Las Huelgas in a

two-part setting. Other

sources contain a three-part

version.

The worship of the Virgin Mary

was the focal point of the

religious ceremonies at the

convent of Las Huelgas. For

this reason a conspicuously

large number of works in the

Codex are dedicated to Mary:

Eya Mater is a

monophonic prosa in refrain

form, which is strongly

reminiscent of the style of

the Cantigas de Santa

María, the pilgrim songs

popular at the time. The work

is a song of praise to Mary,

and the initial letters of

each third line form the

acrostic Ave Maria.

This work is to be found in no

other manuscript.

O Maria maris stella

was perhaps one of the

best-known Marian motets of

the Ars antiqua. It is to be

found in more than ten other

sources and in the most

diverse forms: in two, three

and four parts, always with

different combinations of

text. The Codex Las Huelgas

also contains various

versions.

Belial vocatur

is known only from the Las

Huelgas manuscript. It is a

Marian motet, in the original

version of which only one part

is provided with a text. It

tells of Candlemas (February

2nd) and of Jesus's appearance

in the temple. With its lively

style and its four-part

setting this composition is

one of the later ones in this

manuscript. The composer makes

use of various ornamented

modes in alternation within

the so-called “Aequipollentia”

style (equality of the various

strands of musical texture).

The music is almost secular in

feeling and is reminiscent of

the words of Pope John XXII in

his papal bull Docta

Sanctorum patrum (1324),

in which he distances himself

from “modern” influences: “The

church melodies are set in

short note values and

inundated with little notes.

In addition the singers

furnish the melodies with

hockets; they brighten up the

melodies with descants; they

add duplum and triplum to the

vocal line. They despise the

basic model of the

Antiphonarium and are no

longer acquainted with it at

all ...”

Quis dabit capiti

is one of the laments

(planctus) from the Codex.

This monophonic work is

composed in the Lydian mode, a

mode which particularly

symbolises harshness and

bitterness. This work, too, is

to be found in no other

manuscript.

Homo miserabilis

is a motet which is to be

found in two other manuscripts

as well, e. g. in the Codex

Bamberg. There the tenor text

is notated in full, which is

not the case in the Codex Las

Huelgas. We have taken the

complete (German) tenor text,

because this defines the

character of the piece to a

great extent and makes the

meaning of the Latin

“commentaries”

in the duplum and triplum

clear. The origin of the tenor

text has not been able to be

established until now. The

motet seems to be a kind of

funeral procession, whereby

the upper voices lament the

transience and misery of

earthly existence, while the

tenor part announces someone's

death (Brumas's?). This work

is a premature “dance of

death”.

Ex agone and Flavit

auster are

performed instrumentally on

this CD, although they are

provided with texts in the

original. Instrumental music

already constituted part of

the musical scenery in the

Middle Ages. Johannes de

Grocheio (second half of the

13th century until the

beginning of the 14th century)

names the cantus coronatus,

the ductia or the stantipes

as instrumental forms in his

treatise De musica.

According to him they were

used above all to accompany

dancing, and were particularly

necessary to prevent young

people from thinking sinful

thoughts. The two works chosen

here are in the form of very

short ductia or stantipes.

The individual puncta

(sections) are separated by

continually recurring,

refrain-like quotations, so

that we can speak here of

original models which have a

vocal as well as an

instrumental form. The

monophonically notated Flavit

auster and also the

twopart Ex agone are

local works which are to be

found in no other manuscript.

The sections of the Mass

Sanctus, Agnus

Dei and Benedicamus

Domino represent

an important component of the

manuscript. Above all Sanctus

and Agnus Dei are more

likely to be early works which

illustrate clearly the

predominance of trope texts:

In both cases the added text

is far more comprehensive than

the original Mass text. Benedicamus

Domino, which is

sung at the end of the Mass

instead of the Missa

est is reallv a

rondellus, whereby the three

voices continually repeat the

same musical material in canon

and in the same dimensions.

This work could one of the

earliest surviving canons.

The interpretation

The interpretation of the

Huelgas Ensemble in based on

five precepts:

1) The reading of the original

notation, and the stimulus

resulting from this to define

style and character, is an

essential prerequisite. We

studied the Codex Las Huelgas

in Spain as early as 1973, and

the interpretation for this

recording came about with the

help of the facsimile

manuscript.

2) We have tried to define the

tempo on the basis of a modal

metre (the verse base is

the norm) and not of a mensural

metric unit. Of

significance here is that

Johannes de Garlandia (c.1240)

described divisio modorum

as fulfilling the function of

rests. Since the tempi of this

recording are, we believe,

nearer to the 13th than to the

20th century, they may

sometimes appear somewhat too

slow to modern ears.

3) Nobody can say with

certainty how Latin was

pronounced in 13th century

Spain.Various specialist are

of differing opinions on this.

Local phonemes (e. g. pacem

as pacem) were

integrated into a system of

pronunciation which is

consistently applied.

4) The music of the Ars

antiqua is a particularly

linear art form, in which each

melody of the contrapuntal

texture represents a world of

its own. Hieronymus de Moravia

(c.1270-c.1310) and Franco of

Cologne (c.1250) describe the

discant as a pleasant-sounding

combination of various

melodies. Almost all

theoreticians einphasise that

the polyphonic forms came

about in an additive process:

the parts were not composed

simultaneously, but added one

after the other. Each part is

an independent composition

with, incidentally, also a

text of its own (with the

exception of the pure

conductus). In the performance

practice of the 13th century

the addition of a new part to

an already existing work was a

fully valid act of

composition. This is why so

many compositions have been

preserved in various forms.

The motet O Maria maris

stella, for example, is

known in versions for two,

three and four voices. And in

the three-part version (which

was based on the already

existing two-part version) the

added voice, which is called

“triplum”, differs from one

manuscript version to another.

Polyphony: an

aggregation of monodies. This

basic principle is applied in

the interpretations of the

Huelgas Ensemble. This is why

several works (for example

recordings Nos. 1, 3, 5 and

13) are interpreted not only

in one and two parts but also

in three- and four-part

versions. A work notated in

four parts thus contains a

two-part and a three-part

composition. The model for

this process is Belial

vocatur. In Crucifigat

omnes the tenor part is

even sung alone; the conductus

was the only form in which the

tenor was not a cantus

prius factus - a

previously known theme - but

an independent composition.

5) It is astonishing that the

art of ornamentation was an

essential element in the music

of the Ars antiqua and that at

performances until now hardly

any attempts have been made to

integrate these much-discussed

ornamentations into the sound

pattern. Nevertheless, as

early as the 9th century

ornamentation was mentioned in

connection with monodic vocal

art, and in the 13th century

whole chapters were devoted to

the diversity of

ornamentation. Hieronymus de

Moravia says himself that

tempi were taken more slowly,

so that the ornaments could be

incorporated. Hieronymus calls

the ornaments flores,

Johannes de Garlandia calls

them florificatio soni.

The Huelgas Ensemble has tried

on this recording to use

various ornaments, well aware

that the resulting sound is

not the whole truth, but that

merely an attempt in this

direction has been made. The

Codex Las Huelgas is a welcome

source here, for the

manuscript is full of a

certain ornamentation sign

(the plica), and a

number of other ornaments are

written out in notes, for

example the reverberatio

at the end of the first

three-part version of O

Maria maris stella.

Without wishing to indulge in

theories, we should like to

name some of the most

important ornaments which we

have used in this recording:

a) Plica: a notated

ornament described in detail

by theoreticians.

b) Flores longi, flores

aperti and flores

subiti: described by

Hieronymus de Moravia. Slow,

moderately fast or

accelerating trills on a

semitone or a whole tone

(vibratos).

c) Reverberatio:

Appoggiaturas before the main

note. Also in combination with

the cantinella coronata,

chromatically raised and

shifted notes. Example at the

beginning of Benedicamus

domino.

d) Tremula vox:

described by Engelbert of

Admont, among others. An

oscillating, repeated sound on

one note. Also known in

Gregorian chant as tristropha.

Can be heard, among others, in

Ex illustri.

e) Vinnola vox: an

ornamental figure which circles

round a note like a vine

tendril round a vine-stock -

hence the name.

The sources used by the

Huelgas Ensemble for the

ornamentation:

- Hieronymus de Moravia (end

of the 13th century): Tractatus

de musica.

- Johannes de Garlandia

(c.1240): De mensurabili

musica.

- Perseus and Petrus (c.1200):

Summa musice.

- Johannes de Grocheio

(c.1300): De musica.

- Franco of Cologne (c.1270):

Ars cantus mensurabilis.

- Engelbert of Admont

(c.1300): De musica.

- Aurelius Reomensis (c.850):

Musica disciplina.

Paul

van Nevel

(Translation: Diana Loos)

|

|

|