|

|

1 CD -

SK 48 045 - (p) 1992

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Flute Concertos |

|

77' 00" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Carl STAMITZ (1745-1801) |

Concerto

for Flute, Strings, 2 Oboes, 2 Horns %

Basso continuo in G major, Op. 29 |

|

16' 16" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

6' 50" |

|

1

|

|

-

Andante non troppo moderato

|

4' 17" |

|

2

|

|

-

Rondo. Allegro |

5' 09" |

|

3 |

| Franz Xaver RICHTER (1709-1789) |

Concerto

for Flute, Strings and Basso

continuo in E minor |

|

19' 50" |

|

|

-

Allegro moderato |

7' 34" |

|

4

|

|

-

Andantino |

8' 12" |

|

5

|

|

-

Allegro, non troppo presto |

4' 04" |

|

6

|

| Johann STAMITZ (1717-1757) |

Concerto

for Flute, Strings and Basso continuo in

G major |

|

13' 09" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

4' 45" |

|

7 |

|

-

Adagio |

4' 55" |

|

8 |

|

-

Presto |

3' 29" |

|

9 |

| Joseph HAYDN (1732-1809) |

Concerto

for Flute, Strings, 2 Horns and Basso

continuo in D major |

|

19'

25"

|

|

| Leopold HOFMAN (1738-1793) |

-

Allegro moderato |

6' 30" |

|

10 |

|

-

Adagio |

7' 54" |

|

11 |

|

-

Allegro molto |

5' 01" |

|

12 |

| Christoph Willibald

GLUCK

(1714-1787) |

"Dance

of the Blessed Spirits" for Flute,

Strings & Basso continuo - from

Orpheus and Eurydice, Act II *

|

|

7' 36" |

13 |

|

|

|

|

Barthold

KUIJKEN, transverse flute

|

TAFELMUSIK

on period instruments |

|

Claire GUIMOND,

transverse flute *

|

Jeanne LAMON,

music director |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Centre in the Square,

Kitchener (Canada) - 20/23 January

1991 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineers

|

|

Stephan Schellmann,

Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus) |

|

|

Editing |

|

Andreas Lemke,

Stephan Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony / Vivarte - SK

48 045 - (1 CD) - durata 77' 00" -

(p) 1992 - DDD |

|

|

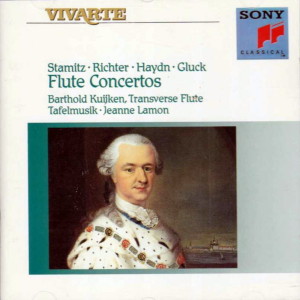

Cover Art

|

|

Kurfürst Karl

theodor von der Pfalz by

Georg Ziesenis (1716-1776) -

Kurpfälzisches Museum, Heidelberg |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The

flute concertos by Johann and

Carl Stamitz, Franz Xaver

Richter and Haydn/Hofmann can

be situated between 1740 and

1780. This period was without

any doubt the golden age of

the transverse flute. This

instrument emerged in its

baroque form in France towards

the end of the 17'th century

and reached a high level of

perfection around 1720 through

the innovative exertions of

some ingenious instrument

makers and a multitude

of fanatical flute virtuosi.

Frederick the Great, who was

said to play the flute more

like a musician than a

Sovereign, indirectly fed the

enthusiasm for the instrument

on the continent. In the

Mannheim circle, to which

three of the flute concertos on

this recording are directly

related, it was the flautist

and composer Johann Baptist

Wendling (1723-1797) whose

skill inspired many other

composers to write for this

instrument. Wendling was one

of the best flautists of his

time, and he performed his art

from the first Mannheim

generation (Johann Stamitz and

Franz Xaver Richter) down to

Mozart's time. Mozart

expressed his esteem for him

and orchestrated one of

Wendling's flute concertos

during his stay in Mannheim in

1777. Wendling gave several

concerts in Vienna and it

cannot be ruled out that

Haydn, Hofmann and Gluck

should also have met him on

these occasions.

The prince elector Karl

Theodor was also a flute

player, and it was during his

reign, between 1743-1777, that

the flourishing Mannheim court

chapel had no fewer than 55

musicians in its service. Of

these, some had originally

played in the older court

chapel in Düsseldorf and

Innsbruck, whereas others came

from the Netherlands and

Italy. However, it was not the

diversity of the musicians but

to the influence of Johann

Stamitz and of his sons Johann

Anton and Carl, that the

spectacular fame of the chapel

was due. Johann Christian

Cannabich (1731-1798) also

played an important role in

this phenomenon.

Johann Stamitz had a

natural talent and a

suggestive authority which

greatly helped him to achieve

firm discipline in the

orchestra. However, he was not

only a good conductor but also

a brilliant composer who left

us a great number of

symphonies and some concertos.

With the compositions of the

Stamitz family however, it is

not always clear which of the

family members was the author,

as it was not common in the

18th century for composers to

indicate their first name on

the manuscripts. At least five

composers signed with the name

“Stamitz” and it is sometimes

difficult to decide which

concertos are by Johann and

which by Carl. With these

precautions in mind, we count

among the works of Johann

Stamitz eleven flute concertos,

one concerto for oboe, and one

for the clarinet which is one

of the earliest solo concertos

written for this instrument.

The enthusiastic comment of

the English composer and music

historian Charles Burney

certainly includes Johann

Stamitz's flute concertos: “He,

like another Shakespeare,

broke through all difficulties

and discouragements; and as

the eye of one pervaded all

nature, the other, without

quitting nature, pushed art

further than any one had done

before him; his genius was

truly original, bold, and

nervous; invention, fire, and

contrast, in the quick

movements; a tender, graceful

and insinuating melody, in the

slow; together with the

ingenuity and richness of the

accompaniments, characterise

his productions; all replete

with great effects, produced

by an enthusiasrn of Genius,

refined, but not repressed by

cultivation.”

Franz

Xaver Richter, who

like Johann Stamitz was of

Bohemian descent, is the

oldest of the composers

included on this recording. It

is not certain whether Richter

studied in Vienna, but in any

case Fux`s Gradus ad

Parnassum was on his

program of study. Besides

being a composer, Richter was

also a professional singer.

From 1747 onwards he actively

participated in the music life

of Mannheim, keeping a

distance, however, from the

fashionable style of

composition, preferring the

more contrapuntal Viennese

musical idiom. He often used

simple motivic work and

uncomplicated imitations to

treat his musical ideas. The

stable thematics of the

orchestral tutti contrasts

with the more embellished flute

part without really

interacting with it. Here one

encounters clarity of texture

and form, but one feels no

rule-breaking power, and no

awareness of new expressive

horizons (Sturm und Drang,

pre-Romanticism). Burney

highly estimated Richter and

praised his inventive baroque

melody, though he reproached

him on the other hand the

excessive use of sequences:

“Mr Franz Xaver Richter should

be distinguished among the

musicians of Mannheim; his

works of various kinds have

great merit; his subjects are

often new and noble; but his

details and manner of treating

them is frequently dry and

sterile; and he spins and

repeats passages in different

keys without end...”

Carl (Philipp) Stamitz

was the son of Johann Stamitz.

He played the violin and the

viola as well as the viola

damore. He was a prominent

member of the Mannheim

school`s second generation of

musicians. After his father's

death, which came when he was

only eleven years old, he

continued his music studies

under Franz Xaver Richter,

Ignaz Holzbauer and Christian

Cannabich. In 1770 he resigned

from the Mannheim orchestra

and moved to Paris, where he

took service with the Duc de

Noailles. Through this

position, he became acquainted

with Gossec, Leduc, Sieber and

Beer. Between 1771 and 1773

his name was mentioned in the

Mercure de France among

the performers of the

“concerts spirituels.”

He also made extensive concert

tours all over Europe, and

encouraged by the success of

his performances and

compositions he decided to

settle as an independent

artist; but just as in

Mozart's case, he was to

experience by the end of his

life that conditions prevalent

in this period made it very

difficult for artists to attain

such a social status.

Consequently he left behind a

considerable amount of debt.

As a composer he essentially

remained loyal to the Mannheim

style, though he enriched it

with influences from Paris,

London and Vienna. He also

composed many works for wind

players among which are

counted at least seven flute

concertos. His flute concerto

in G major, which was

published as his opus 17 in

1779, amply demonstrates his

craftsmanship: good and

appealing musical themes,

clear structure, with an

expressive but simple harmony

so as to retain transparency.

The flute part aims less at

virtuosity than in his

father's concertos, so that

the composition as a whole

makes a stronger impression.

The Andante exemplifies

once more the melodious ideal

of the Mannheim school. In

this regard, Johann Adam

Hiller wrote in 1781 “Style in

music means the art of

composing a melody. With

harmony one can not speak of

style, because harmony alone,

without a melody has but

little expressive power or

character.”

The authorship of “Joseph

Haydn's” flute concerto in D

major was in doubt for a long

time: we know the work through

three manuscript sources of

which one bears Haydn's name;

the others claim Hofmann as

the author. The Breitkopf

Catalogue mentions the work in

1771 and 1786 as a concerto by

Haydn but in 1781 the same

work was sold as a work by

Hofmann. The Ringmacher

catalogue shows this concerto

as Hofmann's composition in

1773. However, in comparison

to Hofmann's other flute

concertos this concerto is of

such superior quality that

there remains a serious doubt

about his authorship.

Leopold Hofmann

was only six years younger

than Haydn and worked for most

of his life in Vienna. He was

a highly accomplished organist

and violinist. Already at the

age of twenty his name was

mentioned in the list of

professional musicians

associated with St Michael's

in Vienna. By 1764 he was

choir director of St Peter's

and in 1768 records list him

as Kapellmeister

there. In 1769 he succeeded

Wagenseil as Hofklaviermeister,

in which function he also

instructed the children of the

imperial family.

During his life Hofmann was

very well known; Charles

Burney included him in his

works, for instance, and in

1768 J. A. Hiller wrote, “The

concertos of Herr Hofmann in

Vienna are better put

together, are well conceived

and with pleasant melodies;

also his harmonic structure is

better than with many other

new composers... (J.A. Hiller,

Wöchentliche Nachrichten

und Anmerkungen, die Musik

betreffend). The Wíener

Diarium of 1766 puts him

on the same artistic level as

Gluck and Haydn, and

attributes to him the

development of a new style

based on that of the Mannheim

school. After having praised a

serious oratorio the author

states: “But serious though

this style is, he is in an

equal degree pleasant and

attractive in his symphonies,

concertos, quartets and trios.

One may say that Hofmann,

after Stamitz, is the only one

to give to the transverse

flute the proper lightness and

melody.”

Haydn envied his success and

could hardly stand him. Once

he described him as a

conceited wag,“who believes he

alone has achieved Parnassus,

and who seeks to undercut me

in all matters...”

The Dance

of the Blessed Spirits

is the name of the ballet in

the second scene of the second

act of Christoph Willibald

Gluck`s opera Orpheus and

Eurydice. The work

consists of three parts: the

outer parts, which are written

in an appeasing 3/4 measure,

use two flutes and string

orchestra, whereas the central

part is assigned to one solo

flute and the string orchestra

(1774 Paris version). Gluck

avoids exagerated

embellishments and

concentrates fully on the

expressiveness of the

intervals. This piece is a

unique representation of the

Elysian Fields; the French

organist and composer Gabriel

Pierné once called it “the

first creation of a truly

musical atmosphere”.

©

1992 Jan De Winne

|

|

|