|

|

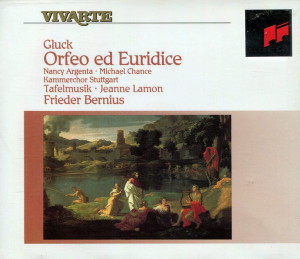

2 CDs

- S2K 48 040 - (p) 1992

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 16/17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Orfeo ed Euridice

(Vienna version: 1762)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Christoph Willibald GLUCK

(1714-1787) |

|

|

|

| Orfeo

ed Euridice -

Azione teatrale per musica in 3 Acts -

Libretto: Ranieri de' Calzabigi |

|

|

|

| Overtura |

|

3' 08" |

CD1-1

|

ATTO I

|

|

20' 31" |

|

| -

Scena 1 - Coro: "Ah, se

intorno a quest'urna funesta" |

3' 17"

|

|

|

CD1-2

|

| -

Scena 1 - Recitativo: "Basta,

basta, o compagni!" - (coro, Orfeo) |

|

|

| -

Scena 1 - Ballo. Larghetto |

2' 34" |

|

CD1-3

|

-

Scena 1 - Coro: "Ah, se

intorno a quest'urna funesta"

|

1' 52" |

|

CD1-4

|

| -

Scena 1 - Aria: "Chiamo il

mio ben così" - (Orfeo) |

5' 20" |

|

CD1-5

|

| -

Scena 1 - Recitativo: "Numi!

barbari Numi" - (Orfeo) |

0' 57" |

|

CD1-6 |

| -

Scena 2 - Recitativo:

"T'assiste Amore!" - (Amore, Orfeo) |

1' 52" |

|

CD1-7 |

| -

Scena 2 - Aria: "Gli sguardi

trattieni" - (Amore) |

2' 14" |

|

CD1-8 |

| -

Scena 2 - Recitativo: "Che

disse? Che ascoltai? - (Amore,

Orfeo) |

2' 25" |

|

CD1-9 |

ATTO II

|

|

25' 44" |

|

| -

Scena 1 - Ballo. Maestoso |

2' 13" |

|

|

CD1-10 |

| -

Scena 1 - Coro: "Chi mai

dell'Erebo fra le caligini" |

|

|

| -

Scena 1 - Ballo. Presto |

0' 36" |

|

CD1-11 |

| -

Scena 1 - Coro: "Chi mai

dell'Erebo fra le caligini" |

1' 08" |

|

CD1-12 |

| -

Scena 1 - Ballo. Maestoso |

1' 05" |

|

CD1-13 |

| -

Scena 1 - Orfeo ed Coro:

"Deh! placatevi con me" |

2' 01" |

|

CD1-14 |

| -

Scena 1 - Coro: "Misero

giovane, che vuoi, che mediti?" |

0' 52" |

|

CD1-15 |

| -

Scena 1 - Aria: "Mille pene,

ombre moleste" - (Orfeo) |

0' 52" |

|

CD1-16 |

| -

Scena 1 - Coro: "Ah, quale

incognito affetto" |

0' 46" |

|

CD1-17 |

| -

Scena 1 - Aria: "Men

tiranne, ah! voi sareste" - (Orfeo) |

0' 40" |

|

CD1-18 |

| -

Scena 1 - Coro: "Ah, quale

incognito affetto" |

1' 30" |

|

CD1-19 |

| -

Scena 2 - Ballo. Andante |

2' 01" |

|

CD1-20 |

| -

Scena 2 - Arioso: "Che puro

ciel, che chiaro sol" - (Orfeo,

coro) |

5' 24" |

|

CD1-21 |

| -

Scena 2 - Coro: "Vieni a'

regni del riposo" |

1' 36" |

|

CD1-22 |

| -

Scena 2 - Ballo. Andante |

2' 43" |

|

CD1-23 |

| -

Scena 2 - Recitativo: "Anime

avventurose" - (Orfeo) |

0' 38" |

|

CD1-24 |

| -

Scena 2 - Coro: "Torna, o

bella, al tuo consorte" |

1' 38" |

|

CD1-25 |

| ATTO III |

|

34' 07" |

|

| -

Scena 1 - Recitativo:

"Vieni, segui i miei passi" -

(Orfeo, Euridice) |

5' 11" |

|

CD2-1 |

| -

Scena 1 - Duetto: "Vieni,

appaga il tuo consorte!" - (Orfeo,

Euridice) |

3' 00" |

|

CD2-2 |

| -

Scena 1 - Recitativo: "Qual

vita è questa mai" - (Euridice) |

1' 33" |

|

CD2-3 |

| -

Scena 1 - Aria: "Che fiero

momento" - (Euridice) |

2' 49" |

|

CD2-4 |

| -

Scena 1 - Recitativo: "Ecco

un nuovo tormento" - (Orfeo,

Euridice) |

3' 32" |

|

CD2-5 |

| -

Scena 1 - Aria: "Che farò

senza Euridice" - (Orfeo) |

3' 34" |

|

CD2-6 |

| -

Scena 1 - Recitativo: "Ah,

finisca e per sempre" - (Orfeo) |

1' 17" |

|

CD2-7 |

| -

Scena 2 - Recitativo:

"Orfeo, che fai?" - (Amore, Orfeo,

Euridice) |

1' 46" |

|

CD2-8 |

| -

Scena 3 - Maestoso |

0' 21" |

|

CD2-9 |

| -

Scena 3 - Ballo: |

|

|

|

| -

I. (Grazioso) |

2' 06" |

|

CD2-10 |

| -

II. Allegro |

3' 04" |

|

CD2-11 |

| -

III. Andante |

1' 00" |

|

CD2-12 |

| -

IV. Allegro |

2' 19" |

|

CD2-13 |

| -

Scena 3 - Coro: "Trionfi

Amore!" - (Orfeo, Amore, Euridice,

coro) |

2' 27" |

|

CD2-14 |

|

|

|

|

Nancy

ARGENTA, soprano (Euridice)

|

Kammerchor

Stuttgart |

|

Michael CHANCE,

alto (Orfeo)

|

Tafelmusik on

period instruments |

|

| Stefan

BECKERBAUER [Tölzer Knabenchor], boy

soprano (Amore) |

Jean Lamon, music

director |

|

|

Frieder Bernius,

conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Forum

am Schlosspark, Ludwigsburg

(Germany) - 6/9 May 1991 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Peter

Laenger (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - S2K 48 040 - (2 CDs) -

durata 48' 52" & 34' 07" - (p)

1992 - DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Scenery

with Orfeo by Nicolas

Poussin (1594-1665) - Archiv für

Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

A New Era

in Opera

"It seems to

me that Gluck and Louis XVI

are going to usher in a new

epoch." This ecstatic eulogy

on Christoph Willibald Gluck's

artistic achievement came from

no less a figure than Jean

Jacques Rousseau: The French

philosopher encapsulated in

words what many contemporaries

- both professional musicians

and music-loving dilettantes -

may well have felt after the

première of the French version

of Orfeo ed Euridice.

This was underlined by the

events which accompanied the

further Paris premières which

followed Orphée.

This seemingly revolutionary

innovation in music drama -

which was always seen not just

as a mere artistic spectacle,

but also as a political

statement - was interpreted

and propagated by Gluck and

his most important librettist

Ranieri de' Calzabigi

(1714-1795) as a great

reforming feat. First of all

Calzabigi and then Gluck

himself never tired of

proclaiming their own worth.

The innovation of which

Rousseau spoke and which

applied to a variety of areas

was to a certain extent in the

air and generally felt to be

actually overdue. Music

theatre and the political

regime were thought to

parallel one another in a way

which is very'difficult to

understand today In

pre-revolutionary Paris, in

the days of Louis XVI, the

supporters of a new form of

music theatre were regarded as

secret republicans. They

automatically turned against

the “Ancien Regime” and the

form of opera which it

favoured, the "tragedie

lyrique", together with its

representatives Lully and

Rameau. And this was the camp

in which Gluck established

himself. For he had set out to

reform the nature and musical

language of opera. From a

musico-historical point of

view this was directed on the

one hand at the unmistakeable

stiffness of French opera,

punctuated by ballets and with

the plot contained in

recitatives, and consequently

rather deficient vocally; on

the other hand Gluck thus

attacked the traditional form

of Italian opera, the “opera

seria”, the dramaturgy of

which, for all its undeniable,

long-standing musical richness

was regarded as narrow and

implausible. This in turn was

based on the dictates and

models of the Imperial Court

Poet in Vienna, Pietro

Metastasio.

Thus Gluck took on two enemies

at the same time: the courtly

French opera with its supposed

musical inflexibility and

neoclassical dramaturgy,

mainly committed to convention

and quite often to reasons of

state, and at the same time

Italian opera with its

confused dramaturgy based on

the never-changing pattern of

all Metastasio operas, which

did at least offer to the

singers the opportunity to

shine with bravura technique

in extensive coloratura arias.

The première in Vienna on

October 5, 1762 of the azione

teatrale Orfeo ed Euridice

marked the first appearance on

stage of a work in which

Gluck's new operatic style was

taken to its logical

conclusion. It was reckoned to

be rather a minor theatrical

occasion in comparison with

some of the great spectacular

operas with many soloists,

extensive choruses and

ballets. Gluck had already

tried out his new musical

language in a ballet evening:

almost exactly a year before Orfeo

his Don Juan received

its first performance at the Burgtheater.

Thus in 1761 Gluck's cherished

dream appeared to be fulfilled

and a 20-year-long artistic

qust to have reached its end.

At the age of 27 he had

produced his first opera (Artaserse)

in Milan in 1741, based on a

libretto by Metastasio. A

great career appeared to lie

before him, for Gluck had not

merely defeated a number of

highly regarded competitors,

but also found himself,

immediately after the

appearance of his operatic

first-born, in a position to

fulfil a number of scritture

- commissions to compose,

rehearse and ronduct new

operas. The all too familiar

style of “opera seria” would

therefore have continued if

Gluck had not displayed clear

signs of lack of enthusiasm.

This reluctance showed itself

in tardy fulfilment of

contracts and eventually,

after four years, he threw in

the towel. There then began a

search lasting many years for

new ways to express himself.

It lead the experienced seria

composer right across Europe.

The lirst stop was in England.

The results of his short stay

in London, from which Gluck

had apparently had higher

hopes, were a meeting and

joint concert with Handel and

two rather cobbled-together

operas.

There followed a period of

travel. Gluck joined for a

number of seasons a travelling

opera company which journeyed

far and wide, putting on opera

perforniances in towns which

had no court or municipal

theatre within their walls. In

this way he approached the

place where he later found

employment - Vienna. After

many years as a freelance he

took a job at the Burgtheater

- in the lowliest possible

position, as a musical

arranger.

Vienna's foreign policy was

aligned with France. One

result of this was that French

theatre was fashionable. At

the Burgtheater this meant

arranging French comic operas

to suit Viennese tastes and

interspersing them with his

own little compositions. That

was just what Gluck did:

having been on the point of

making a European career as a

composer of opera seria,

he modestly applied himself to

the task of creating mostly

simple, indeed very simple

ariettas and songs lasting a

few minutes, in order to fit

them into the imported

material. One can scarcely

imagine how great his

antagonism to traditional

opera must have been, that he

should have been prepared to

undertake such work in his

search for something new.

At last the opportunity came

for which he must have yearned

for so long: the artistically

inclined impresario of the Burgtheater,

Count Durazzo, was a strong

supporter of Gluck. He was

thus able, with a number of

others of like mind, to put on

a complete work in the new

style, namely the ballet Don

Juan, ou le

Festin de Pierre. This

ballet about the “stone guest”

was musically entirely new

territory. The flow of the

music was novel, quickly

adapting itself to the ever

changing situations of the

plot, yet imbued with the

clarity of expression which

later became so typical of

Gluck, based upon economy of

orchestration and melodic

simplicity. Gluck thus

replaced the hitherto

prevailing magnificence of the

Court Opera. This was the Age

of Enlightenment and Gluck

gave musical expression to the

“cri de la nature” demanded by

Rousseau. A year later Gluck

pursued his compositional

ideals even more determinedly

in Orfeo. The score no

longer contains the coloratura

passages so much favoured by

the system of leading men and

ladies; instead there were

simple, folk-like melodies,

which must have delighted

Johann Gottfried Herder,

Gluck's contemporary and a

collector of folk songs. In

place of extended da capo

arias Gluck wrote for his Orfeo

short ariettas which were

seamlessly woven into the flow

of the recitatives. The high

points of the score are,

however, still recognised as

being the songs of the

protagonist.

Most of Gluck's contemporaries

must have been amazed at this

unexpected simplicity: that at

least is implied by the few

surviving accounts of the

première. For example: “It is

an entirely unusual play; I

never saw anything like it.

The action and the music are

highly effective and induce a

sadness which penetrates deep

into the soul, making one

submit completely to the

poetry It seems that the

composer, the celebrated

Gluck, was concerned to

produce a tragic masterpiece,

in which he has certainly been

successful.” Very early on

experts appear to have

correctly assessed the quality

of the work - Rousseau's later

judgment, delivered after the

première of the Paris version,

testifies to this. They were

not troubled by the allegedly

dark and gloomy atmosphere of

the opera, the transparent

orchestration of which, with

its total lack of

counterpoint, was well adapted

to the required naturalness.

Gluck himself described the

new musical ideal as follows:

“My music is only concerned to

achieve the maximum expression

and the reinforcement of the

performance and the poetry.

For this reason I make no use

of trills, runs and cadenzas,

with which the Italians are so

profligate.”

Later in life

Gluck felt compelled, as a

result of a quarrel with

Calzabigi, with whom he broke

off relations after

collaborating on three works,

to acknowledge his

contribution to the new genre.

Presumably he appreciated that

his musical ideal could not be

realised without a text of

equal merit. His operatic

reform would not have been

possible with Metastasio's

texts and flowery turns of

phrase. The realisation of the

new dramatic ideal required

the application of the same

logic in both text and music.

Gluck himself said: “If I

allowed the invention of the

new Italian operatic style,

the success of which has

justified the experiment, to

be attributed to me, I should

reproach myself most severely.

The main credit belongs to M.

Calzabigi.” Rousseau's verdict

on Orfeo was based on

the successful 1774 première

of the French version Orphée

et Eurydice. Its most

important characteristic is

the adaptation of the original

castrato role as a tenor part.

In addition the part of

Eurydice was significantly

expanded and a number of

ballets were added. Gluck took

the best known of these, the Dance

of the Furies, from his

first reform work, the Don

Juan ballet.

One of Gluck's greatest

admirers was Hector Berlioz.

He used many examples from

Gluck's scores for his

treatise on orchestration. He

also adapted Orfeo ed

Euridice, or Orphée

et Eurydice, thinking it

necessary to make it more

acceptable to current taste.

The Vienna castrato version

was impracticable for obvious

reasons. He wanted to make use

of the expanded part of

Eurydice, but also to cut on

dramatic grounds the many

ballets,while retaining the

celebrated Dance of the

Furies. The result of

his efforts was a patchwork in

which the part of Orpheus was

sung by a contralto. This is

the version in which the opera

has been performed far into

our century, until the

appearance of Gluck's

collected works in the sixties

again cleared the way for the

original versions and

therefore for the Vienna

version of 1762 used on this

recording.

Nikolaus

de Palézieux

(Translation:

© l992 Gery Bramall)

|

|

|