|

|

1

CD - SK 62 823 - (p) 1997

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sacred Music |

|

74' 46" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Joseph HAYDN

(1732-1809) |

|

|

|

| Missa

in B flat major, Hob. XXII: 12

"Theresienmesse" |

|

37' 32" |

|

| -

I. Kyrie |

4' 35" |

|

1

|

| -

II. Gloria |

10' 17" |

|

2

|

| -

III. Credo |

9' 25" |

|

3

|

| -

IV. Sanctus |

1' 58" |

|

4 |

| -

V. Benedictus |

5' 13" |

|

5 |

| -

VI. Agnus Dei |

6' 04" |

|

6 |

| Missa

in Augustiis in D minor, Hob. XXII: 11

"Nelsonmesse" |

|

36' 58" |

|

| -

I. Kyrie |

4' 16" |

|

7 |

| - II.

Gloria |

10' 22" |

|

8

|

| -

III. Credo |

9' 05" |

|

9 |

| -

IV. Sanctus |

1' 58" |

|

10 |

| -

V. Benedictus |

5' 44" |

|

11 |

| -

VI. Agnus Dei |

5' 33" |

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

| Ann

Monoyios, soprano |

Tölzer

Knabenchor / Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden, chorus

master |

|

| Svetlana Serdar,

contralto |

Tafelmusik

on period instruments |

|

| Wolfgang Bünten,

tenor |

Jean Lamon,

music director |

|

| Harry van der

Kamp, bass |

Bruno Weil, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Stadtpfarrkirche

"Maria Himmelfahrt", Bad Tölz

(Germany) - 9/11 September 1996 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Assistant Engineer |

|

Nikolaus

Radeke (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 62 823 - (CD) -

durata 74' 46" - (p) 1997 - DDD |

|

|

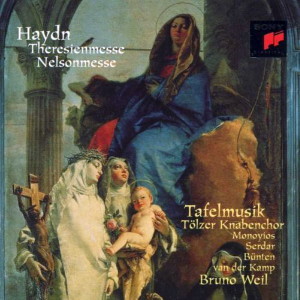

Cover Art

|

|

Madonna

con le sante Caterina da Siena,

Rosa da Lima col bambino e

Agnese da Montepulciano

(1748) by Giovanni Battista

Tiepolo (1696-1770) - Santa Maria

del Rosario, Venezia. Courtesy:

Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte,

Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Teresa

Mass

This is the fourth of the six

great masses that Haydn wrote

upon his return from England

in the autumn of 1795. To show

its position more graphically,

the following table will

perhaps be of use:

- Missa Sancti Bernardi de

Offida (Heiligmesse) in

B flat major, 1796

- Missa in tempore belli (Paukenmesse)

in C major, 1796

- Missa in angustiis (Nelson

Mass) in D minor, 1798

- Missa (Theresienmesse)

in B flat major, 1799

- Missa (Schöpfungsmesse)

in B flat major, 1801

- Missa (Harmoniemesse)

in B flat major, 1802

As the table shows, our Mass

is called in Austria the Theresienmesse

(Theresa Mass), because it was

assumed that Haydn had

composed it for the Empress

Marie Therese (not to be

confused with Marie Theresa,

who had died lang before;

Marie Therese was the daughter

of King Ferdinand IV of Naples

and the wife of the Austrian

Emperor Francis II, for whom

Haydn wrote “Gott erhalte

Franz den Kaiser”; today this

melody is known as the

national anthem of Germany).

Recent research has, however,

shown beyond a doubt that the

Mass was written, like the

other five, for the Name Day of

Princess Maria Hermenegild,

the wife of Haydn's patron

Nikolaus II Esterházy. In fact

Haydn did compose a work for

the Empress: the great Te

Deum of 1799 (the same

year as the Theresienmesse),

and this is why, no doubt, the

other major work of 1799 was

ascribed to Marie Therese.

Haydn was very fond of his

Princess, and Maria

Hermenegild saw that relations

between her arrogant,

imperious husband and his

Kapellmeister (who was now

“Doctor of Oxford” and not

disposed to be treated like a

servant) were kept serene. She

did a great deal to make

Haydn's old age comfortable,

and saw to it that he had his

favourite wine (Malaga) served

to him from the Princely

cellars, and that his doctor's

bills were paid. In return, as

it were, Haydn wrote for her

some of his most inspired

music: in Princess Maria, the

world has a lot to be grateful

for.

In 1799, Prince Nicolaus's

band was slightly retluced in

size but Haydn, like Bach or

any other 18th -century

composer, made do with the

available forces, which were

substantial enough: he scored

his new Mass for two

clarinets, two trumpets,

kettledrums, strings, organ,

four soli (soprano, alto,

tenor, bass) and hoir - it was

a good deal more than Bach

often had at his disposal!

Apparently the bassoons, which

would have been part of the basso

continuo, received their

“own” part at the last minute;

since they were once part of

the original performance

material of the Mass, still at

Eisenstadt Castle.

In 1799, the Princess's Name

Day fell on Sunday the 8th of

September. The night before,

Eisenstadt Castle was host to

a celebration in her honour.

“At six in the evening”,

writes a contemporary in his

diary, “there

was Turkish Music in the

square, then a French play. At

the end a decoration with the

portrait of the Princess. The

Frenchmen rolled across [the

stage] like an army, with

caricatures using grenadiers,

fifes and drums; the players

also dressed in Hungarian

costume; they stuttered as

they read off their speeches

and congratulations [to the

Princess]. The spectacle

wasn't finished till 11.30.”

The next day, probably at

11.00 am., the Mass was first

performed in the “Bergkirche”

(Church on the Hill), a few

minutes on foot from the

Castle. Afterwards there was

an immense banquet in the

Great Hall of the Castle. Our

diarist reports: “At 3.00 we

saw the table in the Great

Hall, fifty-four strong. A lot

of toasts were drunk, which

were always announced by

trumpets and drums from the

gallery and by the thunder of

cannon in front of the Castle.

The Prince also drank a

toast to Haydn's health,

and everyone joined in. The

banquet went on till 5 o'

clock, but the spirit wasn`t

really cheery despite eighty

dishes and all sorts of

wines.“ That evening there was

a grand ball.

The Kyrie of our Mass

is in three parts: a solemn,

slow introduction, in the

manner of the Salomon

Symphonies, but more extended,

leads to a strict fugue, the

theme of which is clearly

based on material from the

introduction (again something

we encounter in the Salomon

Symphonies, especially

Nos. 98 and 103). This middle

section moves in a stately,

contrapuntal fashion to the

dominant, where the four

soloists announce the “Christe

eleison”, rather like a second

subject in sonata form. The

fugue is then taken up again,

to arrive slowly at a big

fermata, whereupon a shortened

version of the slow

introduction concludes the Kyrie.

As will be clear when hearing

the music, Haydn has worked

out a highly interesting and

effective marriage between

symphonic style, sonata form,

fugue and overall tripartite

form (A-B-A), while the middle

section also neatly subdivides

into three parts.

The Gloria is also

separated into several

sections:

1) the opening “Gloria in

excelsis”, with a stirring

orchestral accompaniment, in

particular the fanfares after

“benedicimus te” and “adoramus

te” which lead to a wonderful

sort of recapitulation

(“glorificamus te”) in which

the violins dance across the

texture in semiquavers, the

clarinets, trumpets and drums

punctuating the whole with

flashes of colour.

2) The Moderato

(“Gratias”) is reached by a

modulation to the dominant of

C, and the movement itself

begins in C major, with a

famous solo for the alto, to

which the other solo voices

are joined, one by one. From C

major we modulate to C minor

and the entry of the choir

with the words “Qui tollis

peccata mundi”;

the trumpets and drums enter,

while the basic movement is a

never-ending series of triplet

quavers in the violins.

3) Vivace,“Quoniam tu

solus sanctus”, back in the

tonic, B flat major: a

predominantly homophonic

beginning turns into another

fugal passage (“amen”)

and back to a kind of

recapitulation of the

beginning of this section,

with extended passages for the

soloists: there is a

startlingly chromatic

modulation back to the tutti

which Haydn repeats (bars 317

et seq.).

Like most of the first parts of

Haydn's credos, this one

begins forte in a very

four-square, solid four-four,

as if Haydn felt that the

Nicene Creed needed to be

shouted from the rooftops by

every believer. The strings

soon settle into semiquavers

which carry the momentum from

bar 3 to the end of the

section. It is a remarkable

tour de force, for the

intensity is carried from first

to last, and even the piano

interjections only serve to

heighten the tension. The

middle section is in B flat

minor, and covers the “Et

incarnatus est” to “passus et

sepultus est”. The whole is

allotted only to the solo

voices. Towards the end the

trumpets in their low register

with soft timpani contribute a

rather sinister, metallic

sound to Christ`s death and

burial. The third section (Allegro)

begins with the “Et

resurrexit” in G minor - a

favourite device of Haydn's

late masses - and winds its

way back to the tonic major,

where, for the words

“judicare” Haydn brings in his

trumpets and kettledrums fortissimo;

later the tempo changes to 6/8

and there is a tightly-knit

fugue (“Et vitam venturi”)

with strong accents (sforzati)

at the beginning of the

theme's second bar.

The Sanctus, with its

subdued Andante

beginning, leads to a swift

section beginning at the words

“pleni sunt coeli et terra”.

Like all Haydn's Sanctus

movements (and because of the

liturgical requirements of the

Mass), this is the shortest of

the six basic sections. The Benedictus

is in the key of G major:

towards the end of his life,

Haydn was most interested in

the relationship of keys by

thirds, as Beethoven was to be

a few years later. It will be

noted that the character of

Haydn's late Benedictus

movements is very often

“popular“ and serene - in this

respect that of the Nelson

Mass is something of an

exception: in many ways this

is the most Austrian of all

the movements in this Mass,

the one that (say) the North

Germans could never have

composed.

The tonal organisation of the

rest of the Mass is typical:

from the submediant major (G

major) we move, for the Agnus,

to G minor, which is the

relative minor of B flat, and

from there back to the tonic

for the “Dona nobis pacem”.

The Agnus Dei is a

sort of huge, slow

introduction, rather severe in

content, while the “Dona nobis

pacem”,

with its fanfares for brass

and timpani, makes a martial

and rather aggressive

conclusion to the work. Note

how beautifully Haydn manages

the juxtaposition of the solo

voices with the choir, and

how, almost imperceptibly, the

material is treated

contrapuntally (bars 101 et

seq.), so that the

purely homophonic sections

stand out. At the end there

are alternating B flats and Fs

for the kettledrums which

sound Beethovenian (bars

198/99) and give the final bars

an almost symphonic richness

and strength.

Nelson Mass

On August 1, 1798, Horatio

Nelson finally caught up with

the French fleet, which he had

been hotly pursuing, in the

bay of Abu Quir, a fishing

village on the Mediterranean

coast of Egypt. And at Abu

Quir, named for “Father

Cyrus”, a Coptic saint, Nelson

blew the French fleet out of

the waters in a daring and

brilliant strategic coup which

thrilled the Allies, desolate

as they were over Napoleon`s

series of brilliant victories.

Napoleon had, in fact, been

within a few day's marching

distance of Vienna in the

Spring of 1797, and in

Eisenstadt, as this great

offensive against the Austrian

armies in Italy had begun,

Haydn had composed a mass

entitled Missa in tempore

belli. In that famous

work, the timpani in the Agnus

Dei had rumbled forth

the ominous advance of the

French armies into Styria -

they actually reached Graz on

the night of April 10, 1797.

Now it was a little more than

a year later. Napoleon had

disappeared across the

Mediterranean, and no one was

sure what his final strategic

aims were - Egypt, perhaps

even a passage to India.

Nelson's great victory on

August 1, 1798, was a turning

point in the long war; it was

to be the first of three

brilliant Nelsonic victories -

Copenhagen and Trafalgar being

the others - which would go

down in history. As Nelson was

chasing the French across the

Mediterranean, Haydn was

sitting down to compose

another war-time mass, the

private title of which he had

entered in his “Entwurf” ur

Draft Catalogue as Missa

in angustiis, or “Mass

in time of straitened

circumstances”. Haydn began

this mass, as the autograph

informs us, “In Nomine

Domini”, on July 10, 1798, at

Eisenstadt and he finished it,

“Laus Deo”, on August 31. The

news of the great victory of

Abu Quir had not yet reached

Austria by the time the mass

was first performed, at

Eisenstadt on September 23,

1798.

Two years later Nelson, Sir

William Hamilton and Lady Emma

Hamilton travelled back to

London overland, via Leghorn,

Ancona and Trieste, arriving

in Vienna towards the end of

August 1800. En route, Lady

Hamilton, a gifted singer, was

given the newly issued score

of Haydn`s The Creation.

On September 3, 1800, Haydn

was at Eisenstadt conducting

the music for the annual

autumn season there, a season

which culminated in a mass on

the Princess's name-day each

year. On September 3, 1800,

Haydn wrote to his publishers

Artaria in Vienna: “[...] One

more thing. My Princess, who

has just arrived from Vienna,

tells me that Mylady Hamilton

is coming to Eisenstadt on the

6th of this month, when she

wishes to sing my Cantata Ariadne

a Naxos: but I don't own

it, and would therefore ask

you to procure it as soon as

possible and send it here to

me.”

The Nelson-Hamilton party

arrived at Eisenstadt on

September 6, 1800. We are

told: “[...] During the four

days of their splendid

entertainment at Eisenstadt by

the Prince and Princess

Esterházy, the triumphal

tourists feasted daily at a

table where a hundred

grenadiers, the shortest of

whom was six feet high, acted

as servitors. The concerts and

balls equalled the cost and

the effectiveness”. We know

from the records in the

Esterházy archives that

Haydn`s great Te Deum

was performed during these

festivities, as well as the

mass of 1798 which

subsequently bore Nelson”s

name. Moreover, Haydn composed

a new cantata for Lady

Hamilton, entitled Lines

from the Battle of the Nile.

The text was written by one of

the Nelson-Hamilton entourage,

Cornelia Knight, and she had

it printed in Vienna. Nelson

gave a copy, with his

signature, to the National

Library in London. Miss Knight

has left us memoirs, in which

she records a dinner with the

Hamiltons, Nelson and Haydn,

whose conversation, she notes,

was “modest and sensible”. We

have another record of the

meeting too: it comes from the

reliable hand of Georg August

Griesinger, Haydn`s later

biographer: “[...] Haydn found

a great admirer in Mylady

Hamilton. She paid a visit

with Nelson to the Esterházy

estates in Hungary, but paid

little attention to their

magnificences and never left

Haydn's side for two days. At

that time Haydn composed an

English song of praise for

Nelson and his victory. Mylady

Knight, Hamilton's companion,

wrote the text.” When Artaria

heard about it, they asked

Haydn to give it to them for

publication. Parenthetically,

the first edition of the

cantata was arranged by Lady

Hamilton herself when she

returned to London. Nelson

gave Haydn his watch as a

keepsake, and Haydn gave

Nelson a pen which he had used

for composing.

So much for this brief

historical survey The mass

itself has two exterior

features which immediately

commend it to the Haydn

scholar: the one is the

unusual key of D minor and the

severity of the two movements

in that key, Kyrie and

Benedictus. The other

is the curious scoring which

includes, apart from the usual

vocal parts and strings, three

trumpets, kettledrums and an

organ which varies from

continuo to solo instrument.

This brilliantly original

orchestration owes its

existence to a highly mundane

fact, namely that in 1798

Prince Esterházy decided to

economise in a war-time

inflationary period and reduce

the size of his orchestra by

eliminating the so-called

“fürstliche Feldharmonie”, or

princely wind band, which

meant pairs of oboes,

clarinets, bassoons and horns.

In point of fact, the

Esterházy band at the time of

the Nelson Mass

contained only a choir, string

players and an organist. A

kettledrum player could always

be found among the local

Eisenstadt musicians, but the

three trumpet players

necessary for the Nelson

Mass were recruited from

Vienna. They were needed so

often that in the end Haydn

persuaded his thrifty Prince

to engage them full time.

Haydn wrote: “Inasmuch as, for

some years now, the 3

trumpeters have been paid per

performance, which amounted to

an annual sum of 111 Fl., in

my humble opinion it would be

something of a saving to pay

them each a cash annual salary

of 25 Fl. and two measures of

corn; they, for their part,

should be obliged to attend

all the performances which are

scheduled, in the church and

otherwise.”

When in 1800 Haydn's orchestra

was once again enlarged to the

full size, one of his

assistants added wind

instruments to the score of

the Nelson Mass. And

when Breitkopf & Härtel

decided to print the score,

Haydn suggested to them that

they might “orchestrate” the

solo organ part with wind

instruments. They followed

Haydn's suggestion but

unfortunately worked from a

bowdlerized copy of the work,

so that the Breitkopf &

Härtel score, which appeared

in May 1803, falsified many of

Haydn's clear intentions.

Although Haydn had no

objections to other people

adding wind instruments to the

work, it is interesting that

he did not do so himself. When

he delivered copies of the

work, as he did to the

Monastery of Klosterneuburg

and the Cathedral Church

Archives of Grosswardein (now

Oradea Mare in Romania), he

invariably sent the original

version, with the three

trumpets, drums and

concertante organ.

As for the inner content of

the work, one of the principal

factors we must bear in mind

is that the Nelson Mass

follows immediately upon the

wildly successful first

performance of The

Creation in April 1798.

In a sense, Haydn's new mass

fulfilled three not quite

simultaneous functions: it was

the composer's personal prayer

of thanks for a monumental

task brought to a thrillingly

successful conclusion; it was

the annual mass for the

name-day of his Princess,

celebrated in September 1798

in the Stadtpfarrkirche

(parish church) at Eisenstadt;

and thirdly, it was Haydn`s

belated thank-offering for the

great victory at Abu Quir, and

as such it quite rightly bears

the name of England's greatest

admiral.

©

1997 H. C. Robbins

Landon

|

|

|