|

|

1

CD - SK 68 255 - (p) 1996

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sacred Music |

|

62' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Joseph HAYDN

(1732-1809) |

|

|

|

| Missa

in tempore belli, Hob. XXII: 9

"Paukenmesse" - for Soloists, 4

Part-Chorus, Orchestra & Organ |

|

34' 42" |

|

| -

I. Kyrie - (Largo · Allegro

moderato) |

4' 33" |

|

1

|

-

II. Gloria - (Vivace · Adagio ·

Allegro)

|

9' 22" |

|

2

|

| -

III. Credo (Allegro · Adagio ·

Allegro · Vivace) |

8' 49" |

|

3

|

| -

IV. Sanctus (Adagio · Allegro con

spirito) |

2' 15" |

|

4 |

| -

V. Benedictus (Andante) |

4' 38" |

|

5 |

| -

VI. Agnus Dei (Adagio · Allegro con

spirito) |

5' 05" |

|

6 |

| Salve

Regina, Hob. XXIIIb: 2 - for

Soloists, String & Concerted Organ |

|

16' 53" |

|

| -

Salve Regina (Adagio) |

7' 55" |

|

7 |

| - Eia

ergo (Allegro) |

3' 27" |

|

8

|

| -

Et Jesum (Largo) - O clemens

(Allegretto) |

5' 31" |

|

9 |

Motetto

"O coelitum beati", Hob. XXIIIa: G

9

|

|

9'

59"

|

|

| -

Aria: "O coelitum beati

amores" (Allegro) |

8' 30" |

|

10 |

| -

Chorus: "Alleluja" (Andante) |

1' 29" |

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

Ann

Monoyios, soprano (1-10)

|

Soloists

of the Tölzer Knabenchor: |

|

Monica Groop,

contralto (1-9)

|

(Matthias Ritter, soprano

| Jonas Will, alto | Daniel Rüller,

tenor) (11)

|

|

Jörg Hering, tenor (1-9)

|

Tölzer Knabenchor

/ Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden, chorus master |

|

Harry van der

Kamp, bass (1-9)

|

Tafelmusik

on period instruments |

|

| Geoffrey

Lancaster, organ (7-9) |

Jean Lamon,

music director |

|

|

Bruno Weil, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Stadtpfarrkirche,

Bad Tölz (Germany) - 31 august

& 1 September 1995 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 68 255 - (CD) -

durata 62' 14" - (p) 1996 - DDD |

|

|

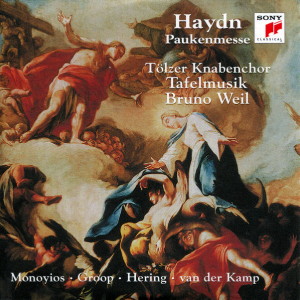

Cover Art

|

|

Mariae

Himmelfahrt" (ca.1748/50) by

Paul Troger (1698-1762) - Dom zu

Brixen, Italy

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Missa

in Tempore Belli and other

sacred works

Haydn was in the midst of his

triumphal second visit to

London when, in the early

summer of 1794, he received a

letter from his Prince,

Nikolaus II. The fourth

reigning Esterházy under whom

Haydn was to serve, Nikolaus,

had become head of the family

after the death of Prince Paul

Anton II in January 1794. Paul

Anton, with little interest in

music, had dismissed the

famous Esterházy band on his

succession to the title in

autumn 1790, and had only kept

Haydn on as nominal

Kapellmeister. Prince Nikolaus

II, by contrast,was keen to

cultivate music at the court

again.

The new Prince,who had a

passion for church music,

proposed to Haydn that he

return to Austria,

reconstitute the band, choir

and soloists, and compose,

once a year, a mass to

celebrate the name day of his

wife, Princess Maria Josepha

Hermenegild. Furthermore, this

was the only actual composing

that Nikolaus expected of his

famous Kapellmeister. Haydn

thought the proposal over and,

despite the large amount of

money he was earning at this

time in England, finally opted

for security in his old age:

he was now over sixty and knew

that, should he become too old

and feeble to compose, the

Esterházy family would support

him. That is exactly what

happened: Haydn scarcely wrote

anything after his Harmoniemesse

of 1802 and lived out his

remaining seven years in

comfortable retirement, with

the Esterházys paying his

doctors” bills and sending him

his favorite wine.

Apart from the oratorios, the

Trumpet Concerto, the late

string quartets and piano

trios, Haydn's last six masses

must be counted as the major

works of his post-London

years. Whereas the last

symphony had been written both

for and in the English

capital, these late masses

are, in some respects,

enormous symphonies to the

glory of God - a miraculous

fusion of various stylistic

elements. Perhaps for the very

last time in music history,

fugue and canon merge

imperceptibly into the

Viennese symphonic frame,

wedding Handelian counterpoint

and Haydnesque form in some

mysterious way.

It is now thought that the Missa

in tempore belli [Mass

in Time of War] is the second

of these six masses. Although

the autograph manuscript is

dated Eisenstadt 1796, the

first performance did not take

place in Eisenstadt but at the

Church of the Piaristes in

Vienna on December 26 of that

year. Haydn conducted and the

church was reportedly packed.

The first performance at

Eisenstadt, with two new

singers just engaged from

Preßburg (now Bratislava,

Slovakia), took place,

according to an Esterházy

official's diary, on Friday,

September 29, 1797: “a new

Mass in C by Haydn was

performed; both [Preßburg]

women sang and both were very

successful."

Some time later, Haydn

enlarged the orchestra, adding

a flute part in the “Qui

tollis”, additional clarinet

parts (these parts exist in

authentic manuscript parts,

corrected by Haydn, in the

Hofburgkapelle - the Imperial

Royal Chapel - in Vienna) as

well as supplementary horn

parts doubling the trumpets;

in our new recording, we

include the flute and clarinet

parts but have omitted the

doubling horns, which may be

regarded as optional.

The title of the mass is

self-explanatory. Austria was

engaged in a disastrous war

with the French, and Napoleon

was winning battle after

battle in Italy. In August

1796, the Austrian Government

issued a proclamation calling

for general mobilization and

prohibiting any talk of peace

until the enemy was pushed

back within his old

boundaries. It is quite likely

that Haydn was just then

composing the Agnus Dei,

with its sinister solo timpani

part (incidentally, using a

much slowed-down version of a

French army drumroll) - hence

the German subtitle for the

work, Paukenmesse or Mass

with Kettledrums.

The Kyrie begins with a

solemn, slow introduction, in

which the timpani thud quietly

and then very loudly, as if to

signal the nature of the mass.

The quick section is

monothematic but in sonata

form, whereby the beautiful

melody with which the soprano

begins also appears in the

dominant for the alto solo.

Gloria and Credo

are each written in three

sections. In the Gloria,

the middle section is an

extraordinary slow movement

with solo violoncello, solo

flute and solo bass voice (“Qui

tollis”), to which the choir

is later added. The third

section (“Quoniam”) is again

quick. The Credo has

as its middle section a slow

movement of great beauty and

intensity ("Et incarnatus

est”), with solo clarinet

writing of rapt poignancy,

whilst the final section of the

Credo, subdivided into

two parts, ends with a

glorious fugue on the words

“Et vitam venturi saeculi.

Amen”.

The Sanctus is in two

parts, a stately opening

followed by a thundering,

quick movement at the words

“Pleni sunt coeli”. In keeping

with its liturgical function,

the Sanctus is always

short. The Benedictus is a

rather ominous sounding Andante

in C minor, which gradually

slips into C major and ends

with the repetition of the

words (first heard at the end

of the Sanctus)

“Osanna in excelsis”.

The Agnus Dei was,

from the outset, justly

celebrated. The kettledrum

solo, which enters quite

unexpectedly at bar 10, is a

stroke of genius, and the big

climax, with the trumpets

raging, is quite terrifying in

its intensity The mass ends

with a powerful, fanfare-

driven “Allegro con spirito”.

It is almost as if Haydn had

altered the words from “Grant

us peace” [Dona nobis pacem]

to “We demand peace.”

The Motet O coelitum beati

seems to be the Latin

“contrafactum” (a translation

that fits the music exactly) of

a lost Italian aria of about

1762 or 1763, when Haydn

composed several Italian

operas for the Esterházy court

at Eisenstadt. Since there

exist other “contrafacta” of

arias from extant Italian

operas by Haydn in this

period, it is assumed that

this Latin motet begins with

such an aria in G. Of this

soprano aria there at one time

existed three manuscript

copies. Of the following

choral Allelaja in C,

with trumpets, four solo

voices, choir and strings with

organ and continuo, there is

only one manuscript extant - a

Viennese copy of the 1760s -

now privately owned, which

includes the opening soprano

aria followed by the chorus.

The Salve Regina in G

minor is one of Haydn's most

admired “smaller” church

pieces from his pre-London

years. In 1766, Haydn's

predecessor, the Princely

Esterházy Chapel Master,

Gregor Werner, died. Haydn was

promoted from “Vice

Capellmeister” to

“Capellmeister” (the spelling

with “C” was customary at that

time), and took over Werner's

duties, foremost of which was

the composition and production

of church music. Up until

Werner's death, Haydn had

composed very little church

music at Eisenstadt - the

major exception being the Te

Deum for Prince Nikolaus

I Esterházy.

One may then understand why

from 1766, church music

suddenly begins to figure so

prominently in Haydn's oeuvre,

beginning with the massive Missa

Cellensis in honorem B.V.M.

of 1766 (later retitled Missa

Sanctae Caeciliae). The

present Salve Regina

was written in 1770 or 1771:

the autograph was originally

dated 1770 but the date was

later changed (almost

certainly by Haydn himself) to

1771, and that is also the

date of the authentic copy in

Joseph Elßler's hand (Haydn's

personal copyist) in the

Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde,

Vienna. This work is scored

for “Quattro voci ma Soli,” in

other words, for four solo

voices (without choir), solo

organ and strings, and the

prominent character of the

organ part suggests that Haydn

may have played it himself,

probably in the Chapel of

Eisenstadt Castle.

The Salve Regina,

although relatively compact,

shows a brilliant sense of

formal integration and

interthematic connection:

notice, for example, how the

material shortly before the

end (“O clemens”) subtly

returns to the thematic stuff

of the opening Adagio.

The ending, in other-worldly pianissimo,

is original, simple and

touching. Haydn was devoted to

the cult of the Blessed Virgin

Mary, and here - as in the

previous Salve Regina

in E major of 1756 - he once

again displays the great depth

of his devotion.

©

1996 H. C. Robbins

Landon

|

|

|