|

|

1

CD - SK 66 295 - (p) 1994

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Paris Sumphonies I

(1785-1786) |

|

73' 04" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Joseph HAYDN

(1732-1809) |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in C major, Hob. I: 82 "The Bear" |

|

25' 20" |

|

| -

Vivace assai |

7' 20" |

|

1

|

| -

Allegretto |

6' 47" |

|

2

|

| -

Menuet · Trio |

3' 49" |

|

3

|

| -

Finale. Vivace |

7' 24" |

|

4 |

| Symphony

in G minor, Hob. I: 83 "The Hen" |

|

24' 09" |

|

| -

Allegro spiritoso |

7' 10" |

|

5 |

| -

Andante |

7' 50" |

|

6 |

| -

Menuet. Allegretto · Trio |

3' 41" |

|

7

|

| -

Finale. Vivace |

5' 28" |

|

8 |

| Symphony

in E-flat major, Hob. I: 84 |

|

23'

23"

|

|

| -

Largo · Allegro |

7' 34" |

|

9 |

| -

Andante |

7' 14" |

|

10 |

| -

Menuet. Allegretto · Trio |

2' 48" |

|

11 |

| -

Finale. Vivace |

5' 47" |

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

| Tafelmusik

on period instruments |

|

| Jean Lamon,

music director |

|

| Bruno Weil, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Glenn

Gould Studio, Toronto, Ontario

(Canada) - 15/19 February 1994 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Markus

Heiland (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 66 295 - (CD) -

durata 73' 04" - (p) 1994 - DDD |

|

|

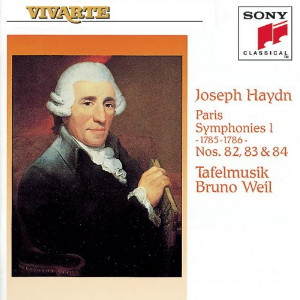

Cover Art

|

|

Haydn

Portrait (1799) by Johann

Karl Rösler (1698-1762) - (Archiv

für Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Haydn:

Paris Symphonies

Haydn's music

was immensely popular in 18th

-century France. In 1764 the

first Haydn symphonies and

string quartets were published

in Paris, and in the course of

the next two decades French

publishers capitalized on the

composer's popularity, issuing

symphonies, quartets, string

trios, piano sonatas, piano

trios, and the Stabat

Mater.

Haydn earned nothing from

these wily publishers; they

secured Viennese copyists, who

fed them “Haydn” in a steady

illegal stream. By the end of

the 1760s the publishers had

run out of authentic material

and began to issue quantities

of spurious works under the

composer`s name. Thus it

happened that symphonies and

quartets by other Austrian

composers whose music sounded

like Haydn's were pirated and

published under his name in

France: favourite sources

include Haydn's brother in

Salzburg, Johann Michael, but

also Carl Ditters von

Dittersdorf, Leopold Hofmann,

Johann Baptist Vanhal, and

Carlos d'0rdoñez.

In one case we can even

observe how the engravers

operated; a set of string

quartets by one Pater Roman

Hoffstetter - a monk in an

obscure South German monastery

- arrived in Paris, and the

engravers began to work on

them. Midway, they decided

that the works could be

marketed as “Haydn”, and so

they erased (but not

thoroughly) Hoffstetter's name

and substituted Haydn`s. In

this fashion came into dubious

being the now-celebrated

“Haydn” Quartets, Op. 3, with

the famous Serenade.

Bearing in mind, then, the

composer`s colossal popularity

in France, we turn now to the

commission that produced

Haydn's finest symphonies of

his pre-London period - the

set of six composed for Paris

in 1785-1786. The initiator of

this scheme was a remarkable

French aristocrat named

Claude-François-Marie Rigoley,

Comte d'Ogny (1757-1790), one

of the backers of a celebrated

Parisian concert organization,

Le Concert de la Loge

Olympique, founded by a

distinguished group of liberal

Freemasons. D'Ogny`s father

had been the Intendant Général

des Postes, a prestigious

position inherited by the son

in 1785.

In order to begin negotiations

d'Ogny asked the orchestra

leader (chef d'orchestre), le

Chevalier Joseph-Boulogne de

Saint-Georges - a colourful

native of the French colonies

who was equally proficient as a

violinist, composer, and

lady-killer - to write to

Haydn with the commission.

Later, in 1871, H. Barbette

reported the details of this

contract in Le Ménestrel,

stating that negotiations

began in 1784 or early 1785,

and that the Concert agreed to

pay Haydn 25 louis d'or

for each of the six symphonies

(“ce qui avait paru à Haydn un

prix colossal, car jusqu'alors

ses symphonies ne lui avaient

rien rapporté'”). Haydn was

also to receive a further 5 louis

d'or for the publication

rights. This fee, according to

a recent study by Gérard Gefen

(Les Musiciens et la

franc-maçonnerie, Paris,

1993: 77), was five times that

which the Concert usually

offered for a symphony. For

comparison, twenty-five louis

d 'or represents about

300,000 fr., DM 100,000, or $

60,000 in today's money.

Haydn wrote at least two

symphonies (Nos. 83 and 87)

and possibly a third (No. 85 -

no autograph survives) in

1785. The others (Nos. 82, 84,

86) were written in 1786,

judging from the evidence of

Haydn's dated autographs. The

first edition of the set,

published by Imbault in Paris,

is ordered: 83, 87, 85, 82,

86, 84, possibly the order in

which Haydn wrote and sent

them to the Loge Olympique.

Artaria in Vienna, who also

published an authentic

two-part edition of the

“Paris” Symphonies (as they

are now universally called),

used the order common today -

although it is chronologically

false.

The orchestra of the Loge

Olympique - “rempli

indépendamment par les plus

habiles amateurs de Paris” -

contained forty violins and

ten double basses. They were

dressed in skyblue coats and

wore swords at their sides.

Symphony No. 85 became a

favourite of Marie Antoinette,

and on Imbault`s first edition

it was entitled “La Reine de

France”. The first performance

appears to have taken place in

the 1787 season, for in

January 1788 the Mercure

de France published an

announcement by Imbault,

advertising the six new works

for sale: “These Symphonies,

of a most beautiful character

and of an astonishing

standard, should be studied

with the most vivid enthusiasm

by those who had the good

fortune to have heard them,

and - even by those who do not

know them. The name of Haydn [sic]

guarantees their extraordinary

merit.”

Reviewing performances of

these new works in the Concert

Spirituel for the 1788 season,

and in particular their

concert of Saturday, April 5,

1788, the Mercure de

France offered the

following Commentary: “In all

the concerts one played

symphonies by M. Haydn. Each

day, one listens more

carefully, and, consequently,

the more one admires the

productions of this vast

genius who constructs, in each

of his works, such rich and

varied developments from a

single subject. [He is] quite

the opposite of those sterile

composers who pass continually

from one idea to another

instead of choosing a single,

variable one; and who produce

mechanically one effect after

another, without linking them,

and without taste. The

symphonies of M. Hayden [sic]

- always sure in their effect

- would have been heard to

even greater advantage had the

room been more resonant, and

if its shape had permitted the

director of this concert to

place the orchestra more

advantageously... ”. Once the

"Paris" Symphonies had been

engraved by Imbault with the

express indications, “Grave

d'apres les partitions

originales appartenant à la

Loge Olympique”, they passed

into history and became so

popular that French audiences

began to attach names to them.

Thus No. 82 became “L'Ours”

(The Bear), No. 83 “La Poule”

(The Hen); and, as we have

seen, No. 85, on the first and

subsequent French editions,

was called “La Reine de

France”. In Sieber's Parisian

edition, passed for

publication on January 9, 1788

by the famous composer Grétry

(1741-1813) (acting for Monseigneur

le Garde des Finances),

No. 85 was moved into first

place, to honour the soon to

be dishonoured queen.

We consider now the “Paris”

Symphonies, not in their

presumed chronological order

(see commentary above), but in

the order in which they are

now generally known.

Symphony No. 82 became

known as “L'Ours” because of

its Finale, in which

people thought they heard a

kind of music that might have

accompanied a dancing tame

bear. The symphony is in C

major, which has become known

as Haydn's “festival” key; he

uses high horns in C alto,

trumpets and kettledrums, as

well as the usual string and

woodwind instruments. In this

case Haydn, perhaps worried

whether the French would have

such instruments, indicates

that trumpets may substitute

for the horns. The first

movement (Vivace assai)

is an enormously powerful

affair, with thundering

fanfares and, later, those

dancing strings in semiquavers

that are so typical of Haydn.

The second subject is a

graceful melody that offsets

nicely the drive and power of

the opening subject. A

brilliant coda is based on the

principal theme. The second

movement (Allegretto) is

dominated by the kind of

melody one imagines having

known all one's life. In it,

Haydn effectively switches

back and forth from major key

to minor. The Menuet is a

ceremonious and beautifully

constructed movement that

appears, like many of the

minuets in these symphonies,

to be a kind of compliment to

French taste. The Finale (Vivace)

returns to the power of the

first movement; its development

section, in particular,

generates an enormous forward

drive, and its coda is a

brilliant conclusion to this

highly masculine symphony.

Symphony No. 83 has

come down to us as “La Poule”

because of the clucking oboe

that accompanies part of the

second subject. The first

movement (Allegro spiritoso)

is dominated by a rather grim

opening melody, fashioned in

such a way that Haydn later

could use it contrapuntally.

The slow movement (Andante)

is a most lively and poetic

piece that uses varied

dynamics and surprise repeated

notes most effectively; we

draw particular attention to

the passage at measure 64 ff.,

in which we hear some of

Haydn's most poetic music. The

bucolic Menuet is followed by

a racy Vivace in 12/8

meter, but this happy and

unconcerned theme .icquires

tiger's claws in the

development section.

Symphony No. 84 opens

with a majestic and beautiful

Largo, while the

ensuing Allegro is one

of the most neatly worked-out

and highly intellectual

movements in this series. The

slow movement is a subtle Andante,

with a contrasting section

designed to offset the

enigmatic quality of the first

section; towards the end is a

cadential six-four chord

followed by a brilliant solo

wind section with pizzicato

strings, constituting a truly

sophisticated cadenza. The

Menuet is more Austrian than

most of the dance movements in

these symphonies; the snap of

the upbeat has something

particularly Viennese about

it. The Finale (Vivace)

is written in the manner of

the fast movements of No. 82;

the violins often race ahead

in semiquavers, supported by a

bass line in quavers. But it

also has a mysterious and

highly effective contrasting pp

section that broadens

considerably upon its

reappearance in the

recapitulation.

©

1994 H. C. Robbins

Landon

|

|

|