|

|

1

CD - SK 66 296 - (p) 1994

|

|

| VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Paris Sumphonies II

(1785-1786) |

|

71' 04" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Joseph HAYDN

(1732-1809) |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in B-flat major, Hob. I: 85 "The Queen" |

|

20' 38" |

|

| -

Adagio · Vivace |

6' 55" |

|

1

|

| -

Allegretto |

7' 33" |

|

2

|

| -

Menuet · Trio |

3' 55" |

|

3

|

| -

Finale. Vivace |

3' 15" |

|

4 |

| Symphony

in D major, Hob. I: 86 |

|

24' 56" |

|

| -

Adagio · Allegro spiritoso |

8' 00" |

|

5 |

| -

Capriccio. Largo |

5' 47" |

|

6 |

| -

Menuet. Allegretto · Trio |

5' 03" |

|

7

|

| -

Finale. Allegro con spirito |

6' 06" |

|

8 |

| Symphony

in A major, Hob. I: 87 |

|

24'

18"

|

|

| -

Vivace |

6' 52" |

|

9 |

| -

Adagio |

6' 41" |

|

10 |

| -

Menuet · Trio |

4' 20" |

|

11 |

| -

Finale. Vivace |

6' 25" |

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

| Tafelmusik

on period instruments |

|

| Jean Lamon,

music director |

|

| Bruno Weil, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Glenn

Gould Studio, Toronto, Ontario

(Canada) - 15/19 February 1994 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Markus

Heiland (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 66 296 - (CD) -

durata 71' 04" - (p) 1994 - DDD |

|

|

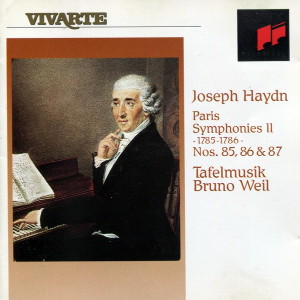

Cover Art

|

|

Haydn

at the Piano (Goauche) by

Johann Zitterer (1761-1840) -

(Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte,

Berlin)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Haydn:

Paris Symphonies

Haydn's music

was immensely popular in 18th

-century France. In 1764 the

first Haydn symphonies and

string quartets were published

in Paris, and in the course of

the next two decades French

publishers capitalized on the

composer's popularity, issuing

symphonies, quartets, string

trios, piano sonatas, piano

trios, and the Stabat

Mater.

Haydn earned nothing from

these wily publishers; they

secured Viennese copyists, who

fed them “Haydn” in a steady

illegal stream. By the end of

the 1760s the publishers had

run out of authentic material

and began to issue quantities

of spurious works under the

composer`s name. Thus it

happened that symphonies and

quartets by other Austrian

composers whose music sounded

like Haydn's were pirated and

published under his name in

France: favourite sources

include Haydn's brother in

Salzburg, Johann Michael, but

also Carl Ditters von

Dittersdorf, Leopold Hofmann,

Johann Baptist Vanhal, and

Carlos d'0rdoñez.

In one case we can even

observe how the engravers

operated; a set of string

quartets by one Pater Roman

Hoffstetter - a monk in an

obscure South German monastery

- arrived in Paris, and the

engravers began to work on

them. Midway, they decided

that the works could be

marketed as “Haydn”, and so

they erased (but not

thoroughly) Hoffstetter's name

and substituted Haydn`s. In

this fashion came into dubious

being the now-celebrated

“Haydn” Quartets, Op. 3, with

the famous Serenade.

Bearing in mind, then, the

composer`s colossal popularity

in France, we turn now to the

commission that produced

Haydn's finest symphonies of

his pre-London period - the

set of six composed for Paris

in 1785-1786. The initiator of

this scheme was a remarkable

French aristocrat named

Claude-François-Marie Rigoley,

Comte d'Ogny (1757-1790), one

of the backers of a celebrated

Parisian concert organization,

Le Concert de la Loge

Olympique, founded by a

distinguished group of liberal

Freemasons. D'Ogny`s father

had been the Intendant Général

des Postes, a prestigious

position inherited by the son

in 1785.

In order to begin negotiations

d'Ogny asked the orchestra

leader (chef d'orchestre), le

Chevalier Joseph-Boulogne de

Saint-Georges - a colourful

native of the French colonies

who was equally proficient as a

violinist, composer, and

lady-killer - to write to

Haydn with the commission.

Later, in 1871, H. Barbette

reported the details of this

contract in Le Ménestrel,

stating that negotiations

began in 1784 or early 1785,

and that the Concert agreed to

pay Haydn 25 louis d'or

for each of the six symphonies

(“ce qui avait paru à Haydn un

prix colossal, car jusqu'alors

ses symphonies ne lui avaient

rien rapporté'”). Haydn was

also to receive a further 5 louis

d'or for the publication

rights. This fee, according to

a recent study by Gérard Gefen

(Les Musiciens et la

franc-maçonnerie, Paris,

1993: 77), was five times that

which the Concert usually

offered for a symphony. For

comparison, twenty-five louis

d 'or represents about

300,000 fr., DM 100,000, or $

60,000 in today's money.

Haydn wrote at least two

symphonies (Nos. 83 and 87)

and possibly a third (No. 85 -

no autograph survives) in

1785. The others (Nos. 82, 84,

86) were written in 1786,

judging from the evidence of

Haydn's dated autographs. The

first edition of the set,

published by Imbault in Paris,

is ordered: 83, 87, 85, 82,

86, 84, possibly the order in

which Haydn wrote and sent

them to the Loge Olympique.

Artaria in Vienna, who also

published an authentic

two-part edition of the

“Paris” Symphonies (as they

are now universally called),

used the order common today -

although it is chronologically

false.

The orchestra of the Loge

Olympique - “rempli

indépendamment par les plus

habiles amateurs de Paris” -

contained forty violins and

ten double basses. They were

dressed in skyblue coats and

wore swords at their sides.

Symphony No. 85 became a

favourite of Marie Antoinette,

and on Imbault`s first edition

it was entitled “La Reine de

France”. The first performance

appears to have taken place in

the 1787 season, for in

January 1788 the Mercure

de France published an

announcement by Imbault,

advertising the six new works

for sale: “These Symphonies,

of a most beautiful character

and of an astonishing

standard, should be studied

with the most vivid enthusiasm

by those who had the good

fortune to have heard them,

and - even by those who do not

know them. The name of Haydn [sic]

guarantees their extraordinary

merit.”

Reviewing performances of

these new works in the Concert

Spirituel for the 1788 season,

and in particular their

concert of Saturday, April 5,

1788, the Mercure de

France offered the

following Commentary: “In all

the concerts one played

symphonies by M. Haydn. Each

day, one listens more

carefully, and, consequently,

the more one admires the

productions of this vast

genius who constructs, in each

of his works, such rich and

varied developments from a

single subject. [He is] quite

the opposite of those sterile

composers who pass continually

from one idea to another

instead of choosing a single,

variable one; and who produce

mechanically one effect after

another, without linking them,

and without taste. The

symphonies of M. Hayden [sic]

- always sure in their effect

- would have been heard to

even greater advantage had the

room been more resonant, and

if its shape had permitted the

director of this concert to

place the orchestra more

advantageously... ”. Once the

"Paris" Symphonies had been

engraved by Imbault with the

express indications, “Grave

d'apres les partitions

originales appartenant à la

Loge Olympique”, they passed

into history and became so

popular that French audiences

began to attach names to them.

Thus No. 82 became “L'Ours”

(The Bear), No. 83 “La Poule”

(The Hen); and, as we have

seen, No. 85, on the first and

subsequent French editions,

was called “La Reine de

France”. In Sieber's Parisian

edition, passed for

publication on January 9, 1788

by the famous composer Grétry

(1741-1813) (acting for Monseigneur

le Garde des Finances),

No. 85 was moved into first

place, to honour the soon to

be dishonoured queen.

We consider now the “Paris”

Symphonies, not in their

presumed chronological order

(see commentary above), but in

the order in which they are

now generally known.

Symphony No. 85, La

Reine de France,

has remained one of the most

popular works in this series.

The introduction (Adagio)

is one of Haydn's veiled

tributes to French taste; the

dotted rhythms call

immediately to mind the

rhythmic characteristics of

the old French overture. The

ensuing Vivace is

based on a striking subject,

highly legato in the top line

and highly staccato in the

bottom. Haydn goes to the

trouble of marking the melody

cantabile. The lead-back

to the recapitulation is

particularly effective. The

next movement is a romance (Allegretto)

based upon an old French

folk-song called “La gentille

et jeune Lisette”, from which

Haydn forms an exquisite set

of variations. The Trio of the

Menuet comes to an

extraordinary high point in

the second section, where time

seems magically to stand still

as Haydn spins out his melody

over a gigantic pedal point in

the horns. The Finale is a

perfect example of

sonata-rondo form, which Haydn

seems not only to have

perfected, but also invented.

An extraordinary tale is

connected with Marie

Antoinette, imprisoned in the

“Temple”- as that fortress was

known - with her husband and

children: “Another of those

who came to the Temple was

Lepitre, a young professor who

became a member of the

provincial Commune on December

2nd [1792]. With him on duty

one morning was Toulan, a man

who did all he could to make

life more bearable for the

royal family. There was a

harpsichord by the door of

Madame Elizabeth`s room, which

he tried to play, only to find

it was badly out of tune.

Marie Antoinette came up to

him: 'I should be glad to use

that instrument, so I can

continue my daughter's

lessons, but it is impossible

in its present condition, and

I have not succeeded in

getting it tune.' Lepitre and

Toulan sent out a message, and

the harpsichord was tuned the

same evening.

As we were looking through the

small collection of music that

day, upon the instrument we

found a piece called La

Reine de France [Haydn's

Symphony No. 85]. “Times have

changed”, said Her Majesty,

and we could not restrain our

tears.”

[John Hearsey, Marie

Antoinette, 1974: 190]

Symphony No. 86 is the

second work of the “Paris” set

to use trumpets and timpani,

which Haydn puts to brilliant

use in the quick movements.

After the D major grandeur of

the opening movement (which

includes a rhapsodic slow

introduction), we encounter

the most enigmatic and

intellectually challenging

movement of the six

symphonies. Haydn calls it a Capriccio

(Largo), and it is

almost like an improvision

that the composer has written

down. It is indeed an unusual

movement, whose emotional

content defies normal

description; it is neither

happy nor sad, but inhabits a

magical world of its own. The

Menuet is a large scale affair

in which we find elements of a

sonata form in miniature; the

middle section works out the

material much in the manner of

a development. Its Trio, on

the other hand, presents no

intellectual challenge; it is

the direct predecessor of the

Austrian waltz, and its

delightful melody and simple

accompaniment stand at the

beginning of a tradition that

was to lead - via Mozart and

Schubert - to the music of the

Strauss

dynasty. The symphony

concludes with a brilliant and

witty Finale (Allegro con

spirito), whose splendid

orchestrational tapestry may

conceal from the unwitting

listener an incredible display

of counterpoint and fine

motivic work.

Symphony No. 87 is in

the bright key of A major.

Haydn employs this key in the

first movement (Vivace)

not only for its enhancement

of the sturdy and rhythmically

concentrated opening, but also

for its adaptability to

singing passages. In these

passages the innate warmth of

A major is so ingratiating

that we feel almost

transported to south of the

Alps. The slow movement (Adagio)

features one of those grand

melodies that might have come

directly from our

grandmother's hymn book. In

this grave but lovely

movement, the fine use of

woodwinds can hardly escape

notice. The rather aggressive

Menuet is set off nicely by a

brilliant oboe solo in the

Trio. The Finale (Vivace)

opens with one of those artful

tunes that later lends itself

to contrapuntal treatment.

Notice especially how Haydn

treats the melody in the

development section.

Altogether, one cannot help

but believe that Haydn

sometimes wrote such movements

backwards, composing, as it

were, the complicated

development section first.

This “facture étonnante”, as

the French referred to it, is

one of the great things about

the “Paris” Symphonies. The

craftsmanship is never

obtrusive, and it never

prevents the listener from

apprcciating these symphonies

purely and directly for their

warmth, strength, and beauty.

©

1994 H. C. Robbins

Landon

|

|

|