|

|

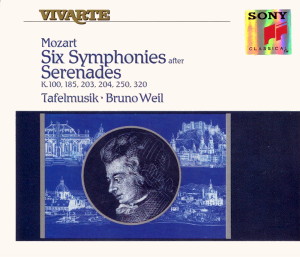

2 CDs

- S2K 47 260 - (p) 1991

|

|

VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 29 & 30

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Six Symphonies after

Serenades |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

(1756-1791) |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D major, K 100 |

|

15' 46" |

|

| - Allegro |

5' 40" |

|

CD1-1

|

| -

Menuetto I · Trio |

2' 16" |

|

CD1-2

|

| -

Andante |

3' 30" |

|

CD1-3

|

| -

Menuetto II · Trio |

1' 51" |

|

CD1-4

|

| -

Allegro |

2' 29" |

|

CD1-5

|

| Symphony

in D major, K 203 |

|

24' 50" |

|

| -

Andante maestoso · Allegro assai |

7' 55" |

|

CD1-6 |

| -

Andante |

7' 14" |

|

CD1-7 |

| -

Menuetto · Trio |

3' 33" |

|

CD1-8 |

| -

Prestissimo |

6' 08" |

|

CD1-9 |

| Symphony

in D major, K 204 ("Haffner" Serenade) |

|

32' 59" |

|

| -

Allegro maestoso · Allegro molto |

6' 41" |

|

CD1-10 |

| -

Menuetto galante · Trio |

5' 38" |

|

CD1-11 |

| -

Andante |

6' 48" |

|

CD1-12 |

| -

Menuetto · Trio I · Trio II |

4' 23" |

|

CD1-13 |

| -

Adagio · Allegro assai |

9' 29" |

|

CD1-14 |

| Symphony

in D major, K 185 |

|

28' 34" |

|

| -

Allegro assai |

8' 03" |

|

CD2-1 |

| -

Andante grazioso |

8' 38" |

|

CD2-2 |

-

Menuetto · Trio I · Trio II

|

4' 25" |

|

CD2-3 |

| -

Adagio · Allegro assai |

7' 28" |

|

CD2-4 |

| Symphony

in D major, K 204 |

|

24' 37" |

|

| -

Allegro assai |

7' 40" |

|

CD2-5 |

| -

Andante |

8' 13" |

|

CD2 6 |

| -

Menuetto · Trio |

3' 26" |

|

CD2-7 |

| -

Andantino grazioso · Allegro |

5' 18" |

|

CD2-8 |

| Symphony

in D major, K 320 ("Posthorn" Serenade) |

|

22' 50" |

|

| -

Adagio maestoso · Allegro con

spirito |

7' 33" |

|

CD2-9 |

| -

Andantino |

11' 37" |

|

CD2-10 |

| -

Finale. Presto |

3' 40" |

|

CD2-11 |

|

|

|

|

TAFELMUSIK

on Period Instruments

|

|

| Jeanne

Lamon, music director

|

|

| Bruno WEIL,

conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Centre

in the Square, Kitchener, Ontario

(Canada) - January/February 1991 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording

Engineers / Editing

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann, Andreas Neubronner,

Markus Heiland (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - S2K 47 260 - (2 CDs) -

durata 74' 13" & 76' 33" - (p)

1991 - DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Mozart

Wien / Salzburg by G. Flurschütz |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

One

of the great delights of 18th

century European music-making,

and often one of the headaches

as well, was the individuality

of traditions from country to

country and from city to city.

On the minus side, for

example, no travelling

musician of that era could

count on a constant pitch.

Nor, without experience, could

he really anticipate the

instrumentation, the

practices, or even the

competence of an orchestra

with whom he might collaborate

in a given place. On the plus

side, however, he was sure to

encounter a unique musical

experience - tailored to the

traditions, needs, and

expectations of each

community.

Like other cities, Salzburg

enjoyed certain traditions

that resulted in special

musical genres. Public

holidays, name days, and other

festive occasions were often

celebrated to the

accompaniment of works we now

might call “Salzburg”

serenades. These serenades

were long, splendidly

heterogeneous, multi-movement

affairs, from which more

unified smaller works could

later be extracted in their

entirety. A serenade might

contain, for example, a

miniature violin concerto, a

four movement symphony,

several movements featuring

wind concertanti, or perhaps a

combination of such diverse

forms - all festively

interspersed with marches and

dances. Other cities and

courts may have encouraged the

composition of colorful

serenades and divertimenti,

but only in Salzburg did

these works, in turn, condense

into unified genres for more

formal use in concert.

The three principal Salzburg

composers of the middle to

late 18th century - Leopold

Mozart, Michael Haydn, and

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - all

used this method of

composition to get maximum

mileage from their incidental

music. From Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart alone we have at least

six clear examples of

symphonies extracted from his

serenades - all in the key of

D major as recorded here. They

range from the first four, not

so well known works (K. nos.

100, 185, 203, 204), to

symphonies whose material is

more familiar, having been

taken from the “Haffner” and

the “Posthorn" Serenades (K.

250 and 320). (The so-called

“Haffner” Symphony, K. 385,

although commissioned by the

same family that requested the

serenade by that name, is a

different work altogether. It,

too, may originally have been

conceived as a part of a

larger serenade for a family

function, but it is mainly the

symphony that has survived.)

The idea of cannibalizing

existing works to make new

symphonies may seem perhaps a

bit cavalier to the composer

of today, who has been taught

to revere idealistic 19th

-century notions of “organic

unity” among the movements of

great musical monuments - not

to mention the popularized

concept of a composer`s

“struggle” towards a final

version. But looking back upon

the 18th century with a

clearer sense of music's

function in society (which

made constant demands upon

successful composers like

Mozart), we realize that

factors as basic as common

keys, appropriate “affects”,

or even compatible lengths

were perfectly acceptable

criteria for grouping

movements into larger forms.

Besides, considering the speed

and ease with which Mozart

composed, the possibility of

maintaining some inner unity

among such movements was not

necessarily lost.

A note concerning

orchestration and text:

because of the disarray in

which some of Mozart's music

was left at his death, and

also because of period

performance practices, we can

only assume the presence of

certain instruments in the

symphonies from the serenades.

The most important decision to

make concerns the tympani, for

which few parts survive in the

revised versions. In some

cases it is unclear if the

parts have been lost, or if a

player was simply expected to

improvise his own.A notable

exception is represented by

the tympani part for K. 250

(recomposed by Mozart but left

incomplete), which has served

as a model for reconstruction.

For the present recording the

symphonies have been supplied

with tympani parts patterned

after this model. In cases of

further text questions the

listener is referred to the Neue

Mozart-Ausgabe, upon

which these performances are

based.

Ostensibly, Mozart's first

symphonic work to be taken

from the serenades was the Symphony

in D major, K. 100

(1769). The Serenade comprises

nine parts, which, in addition

to the five symphonic

movements, include an opening

march and three movements of a

sinfonia concertante for oboe

and horn. The Symphony is cast

in a relatively compact five

movements: Its Allegro

begins directly, with no

introductory section; its two

Menuettos show Mozart's

humorous style at its best;

its simple Andante is

especially enhanced through

muted strings and pizzicato

effects; and its final 3/8

Allegro packs the listener off

with a delightfully spirited

bonhomie.

Extracting the Symphony

in D major, K. 185

(1773) from its serenade is

now a task for the performer,

because we no longer possess a

separate score of parts for a

symphony. Nevertheless, we

know that a separate symphony

once existed. The serenade was

probably written as Finalmusik

in the summer of 1773. Finalmusik

was the name given to

serenades composed for the end

of an academic semester. Of

the eight serenade movements

(including a march and a

mini-concerto for violin), the

symphony is made from the Allegro

assai, the Andante

grazioso, the Menuetto

and two Trios, and the Adagio

- Allegro assai. The

movements of this work are

slightly larger in scope than

some other symphonies in this

period, and this is the first

of Mozart`s symphonies to

feature a slow introduction to

one of the Allegro

movements. There is a

concertante spirit in several

of the movements - notably in

the Andante grazioso,

where the winds are featured,

and in the first Trio of the Menuetto,

where a solo violin echoes its

larger role in the serenade.

In the second Trio, the

listener may also hear an

early version of the spirit of

Figaro in his cavatina

“Se vuol ballare”.

The Symphony in D

major, K. 203

(August 1774) is again taken

from a Finalmusik,

written for the semester's end

at Salzburg University. This

one has nine movements,

including a march and a

complete violin concerto, in

addition to the symphony. Like

K. 185, the symphony features

slow introduction, this time

to the first movement (Andante

maestoso - Allegro assai)

- short but flowery and

serious, as a harbinger of the

engaging and exciting movement

to follow. The Andante

is also muted, and it features

an unusually florid

accompaniment. A stately Menuetto

is followed by a piquant but

dashing Prestissimo

that can be a challenge to any

orchestra.

The Allegro assai of Symphony

in D major, K. 204

(August 1775) begins with

three “annunciatory” chords,

an opening convention popular

among composers in several

countries in this period. We

do not know exactly the

occasion for which the

Serenade was composed, but the

diary of J. J. Ferdinand von

Schiedenhofen, Privy

Councillor to the

Prince-Archbishop, reveals

that he heard the Serenade on

at least two different

occasions: “1775, 9. August:

After dinner to Final Musik

composed by Mr. Mozart.”- and

- “23. August: After dinner to

Final Musik by Mozart.” It is

a safe assumption that K. 204

was meant to celebrate the

semester's end or even

graduation day of Salzburg

University in the summer of

1775. The Finalmusik

features eight movements,

including another mini-violin

concerto. The soloistic

woodwind writing in the Andante

and the Trio from the Menuetto

confirms that this symphony

arises from a concertante

spirit. The finale is unusual

in its metric structure,

alternating between an Andantino

in 2/4 and a cheerful Allegro

in 3/8.

The five-movement Symphony

in D major, K. 250

(July 1776), taken from the

famous “Haffner”

Serenade, is one of the most

ambitious orchestral works of

this period in Mozart's

career. The Serenade itself

has nine movements. In

addition to the symphonic

movements they include an

opening march and three

movements of a violin concerto

in G major. The Serenade was

written for the wedding (21

July 1776) of “Sgr. [Franz

Xaver] Spath”

with “Sgra. Elisabetta

Haffner”, a sister of Mozart`s

childhood friend Sigmund

Haffner for whom the Symphony

K. 385 was written. In a

proper alla breve

tempo the opening Allegro

maestoso reveals

immediately the spirit of the

original occasion, and

possibly even a bit of “mail

carriage” imagery in the last

paced dactyl rhythms of the

violins. This exuberant

atmosphere is continued Allegro

molto. The listener will

hear a small brass fanfare in

the penultimate seconds of

this movement, just before the

final sweep down by the

orchestra. In the original

serenade Mozart left this

space empty, so that the final

sweep comes as .in unexpected

surprise. Maestro Weil

speculates that in Mozart's

opinion such a joke might have

gone over better in a Salzburg

garden than in a big city

concert setting, so that in

extracting the symphony Mozart

added the fanfare to fill the

space and bring the listener

safely to the conclusion.

In fact, there are several

interesting comparisons to be

made between the serenade and

the symphonic version -

differences that might suggest

a delightful

scenario. In the original

serenade the bassoons are

suddenly missing from the Menuetto

galante, and in its

charming little four-part Trio

the second violin part is an

“Alberti” or “broken chord”

accompaniment: a single player

might thus provide a complete

harmonic accompaniment. This

scoring would allow four

players - two violins, a

viola, and some sort of bass

instrument - to leave the

orchestra momentarily and play

the Trio as a surprise “echo”

from some distant point,

providing a little scene not

unlike the later first act

finale setting of Don

Giovanni! One can well

imagine Mozart omitting the

bassoons in order to give one

of the players time to get

from the main orchestra to

perhaps a balcony or some

other point in order to

provide the bass instrument

(which Mozart left

conveniently unspecified) for

the Trio. A bassoon, after

all, is far more portable than

a contrabass - and in any case

Mozart would have depended on

the latter to remain in the

orchestra to support the

return of the Menuetto.

Of course, none of this would

work in a concert situation,

so the symphonic version is

more conventional - simple

repeated notes in the second

violin, bassoons reinstated.

The following Andante

is identical with the

original, followed by a second

Menuetto with two

Trios. Multiple menuets and

trios may not have been

standard features of symphonic

works in this period, but one

must remember that the

“serenade” symphonies are

indeed special forms - with

equally special festive

associations. The finale's

opening Adagio is one

of Mozart's most engaging and

beautiful creations, followed

by an exuberant Allegro

assai worthy of anyone's

wedding day.

Once beyond the portentous Adagio

maestoso beginning of

the Symphony in D

major, K. 320 from

the “Posthorn” Serenade (3

August 1779) the Allegro

con spirito hurries

along in another 18th -century

convention particularly

well-handled by Mozart. It is

the syncopated “motor” effect

that propels the movement

forward; other famous examples

of it occur in the first

movements of the “Prague“

Symphony (K. 504) and the D

minor Piano Concerto (K. 466).

The Symphony is taken from a

serenade of nine movements,

named for the “posthorn”

effect in one of the menuet

trios. It is a work that

deserves mention alongside

more famous works, in that it

shows some of the techniques

of a maturing and serious

Mozart. The reintroduction of

the Adagio maestoso

woven into the meter of the Allegro

con spirito confirms the

“portentousness” of which we

spoke earlier, and

demonstrates Mozart's concern

with dramatic unity. The Andantino

is one of Mozart's finest

essays in a minor key, and its

almost theatrical calm is a

truly great subject for the

student of 18th -century

affects. The finale, Presto,

is breathtakingly short, but

the quality of its musical

ideas and their working-out

makes it a fitting end to this

magnificent symphony.

David

Montgomery

|

|

|