|

|

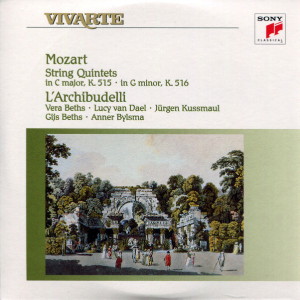

1 CD -

SK 66 259 - (p) 1995

|

|

VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 32

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String Quintets |

|

62' 50" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

(1756-1791) |

|

|

|

| Quintet

for 2 Violins, 2 Violas and cello no. 3

in C major, K 515 |

|

31' 07" |

|

- Allegro

|

11' 26" |

|

1

|

| -

Menuetto. Allegretto · Trio |

5' 11" |

|

2 |

| -

Andante |

7' 46" |

|

3 |

| -

Allegro |

6' 54" |

|

4 |

| Quintet

for 2 Violins, 2 Violas and cello no. 4

in G minor, K 516 |

|

31' 19" |

|

-

Allegro

|

10' 06" |

|

5 |

| -

Menuetto. Allegretto · Trio |

4' 14" |

|

6 |

| -

Adagio ma non troppo |

7' 38" |

|

7 |

| -

Adagio · Allegro |

9' 21" |

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

| L'Archibudelli |

|

| - Vera Beths, violin |

|

| - Lucy van Dael, violin

|

|

| - Jürgen Kussmaul, viola |

|

| - Gijs Beths, viola |

|

| - Anner Bylsma, cello |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Alte

Reitschule, Schloß Grafenegg

(Austria) - 28 June / 1 July 1994 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 66 259 - (1 CD) -

durata 62' 50" - (p) 1995 - DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Park

Schloß Schönbrunn, Wien by

L. Janscha / J. Ziegler

(1749-1812) - Photo: Archiv für

Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

It

seems to have been a string

quintet by Michael Haydn that

inspired Mozart to write his

own String Quintet in B flat

major K. 174 in 1773.An early

exercise in style, it remained

very much an exception at this

time, with Mozart clearly

preferring to flex his

compositional muscles on the

string quartet, in which he

rose to the challenge of

treating all the voices as

equal partners within the

musical argument. Not for

another fourteen years did he

return to the string quintet,

but when he did so, it was to

turn it into the spiritual

heart of his instrumental

œuvre and to turn out four

great masterpieces that

transformed the string quintet

into the favoured medium of

Mozart's late chamber style.

The forces deployed in string

quintets were still not fixed

in the 1770s: while a number

of composers experimented with

two violins, two violas and

double bass, others opted for

three violins, viola and

double bass. By the following

decade, however, the

instrumental combination was

largely settled, at least in

Vienna: while the Madrid-based

Luigi Boccherini was busy

writing quintets with two

cellos (Boccherini himself

played the cello and regularly

performed with an existing

quartet made up of court

employees), Mozart decided in

favour of two violins, two

violas and cello.

Mozart's own autograph

“Verzeichnüß” sheds light on

the genesis of his four late

string quintets. The C major

Quintet K. 515 was completed

on April 19,

I787, the G minor Quintet K.

516 on May 16 of the same year

- both shortly before he began

work on Don Giovanni.

It is unclear, however,

whether he wrote them in

response to a particular

commission. All that we can

say for certain is that he

offered them for sale by

subscription in April 1788, “beautifully

and correctly written”, but

that demand seems to have been

somewhat sluggish, since, two

months later, he was obliged

to delay publication in the

hope that more subscribers

would be found. Only a year

previously, a Viennese

contributor to Cramer`s Magazin

der Musik had complained

that Mozart's new string

quartets were “too highly

seasoned” and that the

composer “aims too high in his

artful and truly beautiful

compositions”. Writers

evidently still found it

difficult to judge an art

which, with all its mysteries

and profundities, transcended

the norms that were customary

at this time.

The opening movement of the C

major String Quintet K. 515 is

a particularly fine example of

Mozart`s ability to use

well-tried formulas in a

highly original fashion. While

the three middle voices fulfil

the function of an

accompaniment, the cello

launches the work with a

broken triad that is answered

by the first violin. This

formula is repeated two times

and is followed by a fermata

typical of Mozart's tendency

to blur the expressive

outlines, after which the two

principal instruments exchange

roles, with the theme now

heard in a muted C minor. The

thematic material is reworked

in the development section,

with Mozart even indulging in

passages of two-part

invertible counterpoint, while

the recapitulation, in which

the previously neglected

subsidiary material is now

allowed to assert itself, is

no less notable for the

density of its contrapuntal

writing.

When the C major Quintet was

published for the first time by

Artaria of Vienna in 1789, the

introductory Allegro was

followed by the Menuetto, an

order suggested by analogy

with that of the work's

companion piece, K. 516. That

the present recording follows

this somewhat unusual ordering

should need no justification.

(Although the pagination of

the autograph score reverses

this order, with the Menuetto

following the Andante; but its

reliability is disputed by

scholars.) The Menuetto

pursues its shadowy course,

with a Trio in F major in

which, following a darkly

chromatic passage, a ländler-like

melody is able to soar aloft

with all the greater freedom.

Only now do we hear the

Andante, which is domínated

from first to last by a

dialogue between first violin

and viola, in the course of

which the latter instrument

gradually asserts its

independence. The final

movement is cast in the form

of a sonata-rondo and allows

the first violin to engage in

flights of virtuosic fancy.

Yet, for all its playful brio,

the movement is equally

notable for its finely

detailed contrapuntal writing

and for its use of the sort of

motivic fragmentation

associated with Joseph Haydn.

The galant and

academic styles are

marvellously balanced here.

In contrast to the hidden

depths of the C major Quintet,

the G minor String Quintet K.

516, although written only a

few weeks later, is of almost

disarming emotional

directness. G minor is the key

of the symphonies K. 183 and

550, of the Piano Quartet K.

478 and of Pamina's second-act

aria from Die Zauberflöte,

“Ach, ich fühl's, es ist

verschwunden”, so that in the

present case, too, the

listener is bound to expect an

equally personal statement on

Mozart's part. Twelve days

after he had completed the

work, his father Leopold died

in Salzburg after a long and

painful illness. At a time

when his thoughts must have

been turning more than ever to

the Grim Reaper, Mozart wrote

a piece in whose opening

movement the almost feverish,

enervatingly beating quaver

accompaniment refuses to be

silenced. Tormenting

hopelessness finds expression

here. Even the second-subject

group which, in defiance of all

convention, opens in the tonic

G minor provides for searing

dissonances with its upward

leap of a diminished ninth.

The Allegro's fatalistic mood

also affects the rugged

Menuetto,while in the

following Adagio in E flat

major - an overcast con

sordino movement -

piercing anguish breaks

through in the second subject

in B flat minor. This second

subject also provides the

material for the expressively

charged, slow introduction to

the final movement, an Allegro

in G major whose carefree

6/8-metre finally drives away

the previous movements' darker

world of minor tonalities.

Whether or not we agree with

Arnold Werner-Jensen that this

final rondo is a “forceful act

of self-emancipation”, there

is no denying that its secrets

are hard to uncover.

Hans

Christoph Worbs

(Translation:

© 1995 Stewart Spencer)

|

|

|