|

|

2 CDs

- S2K 62 879 - (p) 1997

|

|

VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 33 & 34

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Vienna Years

1782-1789 - Sonatas, Fantasies &

Rondos |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

(1756-1791) |

|

|

|

| Piano

Sonata in C minor, K 457 |

|

19' 41" |

|

| - Allegro |

6' 16" |

|

CD1-1

|

| -

Adagio |

8' 41" |

|

CD1-2

|

| -

Molto allegro |

4' 44" |

|

CD1-3

|

| Fantasie

in C minor, K 475 |

|

12' 11" |

|

| -

Adagio · Allegro · Andantino · Più

allegro · Primo tempo |

12' 11" |

|

CD1-4

|

| Minuet in D

major, K 355 (576b) |

|

3' 02" |

CD1-5

|

| Rondo in D

major, K 485 |

|

6' 49" |

CD1-6 |

| Piano

Sonata in F major, K 533/494 |

|

23' 58" |

|

| -

Allegro |

7' 34" |

|

CD1-7 |

| -

Andante |

9' 23" |

|

CD1-8 |

| -

Rondo. Allegretto (K 494) |

6' 51" |

|

CD1-9 |

Fantasie

in D minor, K 397 (385g) -

Fragment, completed by another

|

|

5' 36" |

CD1-10 |

| Rondo

in A minor, K 511 |

|

10' 48" |

|

| -

Andante |

10' 48" |

|

CD2-1 |

| Piano

Sonata in C major, K 454 |

|

7' 52" |

|

| -

Allegro |

2' 48" |

|

CD2-2 |

| -

Andante |

3' 23" |

|

CD2-3 |

| -

Rondo. Allegretto |

1' 41" |

|

CD2-4 |

| Adagio in B

minor, K 540 |

|

6' 47" |

CD2-5 |

| Piano

Sonata in B flat minor, K 570 |

|

18' 21" |

|

| -

Allegro |

5' 45" |

|

CD2-6 |

| -

Adagio |

9' 02" |

|

CD2-7 |

| -

Allegretto |

3' 34" |

|

CD2-8 |

| Piano

Sonata in D major, K 576 |

|

14' 16" |

|

| -

Allegro |

5' 30" |

|

CD2-9 |

| -

Adagio |

4' 40" |

|

CD2 10 |

| -

Allegretto |

4' 06" |

|

CD2-11 |

| Fantasia

in C minor, K 396 (385f) |

|

8' 00" |

CD2-12 |

| (after

the fragment of a sonata movment for

violin and piano arranged for piano

and completed by Maximilian Stadler) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jos van

Immerseel, pianoforte (Pitch:

a' = 430 Hertz)

|

|

| Instrument:

Anton Walter facsimile, Vienna

(1790-1800), by Christopher Clarke, Cluny

1988 (from the Immerseel-Chevallier

collection) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutheran

Church, Haarlem (The Netherlands)

- 31 October / 4 November 1996 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus) |

|

|

Assistant Engineer |

|

Karsten

Renz (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - S2K 62 879 - (2 CDs) -

durata 71' 25" & 66' 26" - (p)

1997 - DDD |

|

|

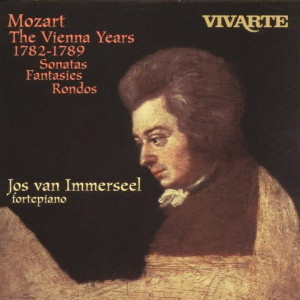

Cover Art

|

|

Mozart

am Klavier by Joseph Lange -

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Considering

all the forms in which the

young Mozart wrote - church

music, operas, symphonies,

divertimenti, concertos, even

sonatas for four hands at the

piano - he came rather late to

the piano sonata. His first six

in the form, K. 279-284

(189d-189h and 205b), were

written for himself, in

preparation for, and during

his sojourn in, Munich when he

was completing his Italian

opera, La finta giardiniera,

in January 1775. Later in his

career, Mozart wrote not only

for himself, sometimes

inviting us to participate in

his joys and sorrows as if we

were a personal friend - but

also for pupils. Some of these

“teaching” sonatas are late

works, such as the deceptively

simple Sonata in C major, K.

545. Sometimes we are

privileged to eavesdrop on a

written-out improvisation,

such as the magnificent

“Phantasie” in C minor, K.

475, which he later attached

to the Sonata K. 457. His last

Sonata in D major, K. 576, was

composed in July 1789 in

Vienna as the first of a

projected set of six for

Princess Friederike of

Prussia. So Mozart's piano

sonatas may be justly

described as representative

crossesections of his hopes,

loves, aspirations and

tragedies (what more

magnificent expression of the

latter than the B minor Adagio

composed in that incredible

year 1788, which also included

the Adagio and Fugue for

strings, K. 546, and the last

three symphonies).

Sonata in C minor, K.

457

Fantasie in C minor, K.

475

Mozart's most ambitious and

large-scale work for solo

piano, these two monumental

pieces were composed in

reverse order: the Sonata was

entered in Mozart's catalogue

on October 14, 1784,while the

“Phantasie” (as he called it)

was entered on May 20, 1785.

Both were united in the first

edition by Artaria and

Company, published in December

1785 and dedicated to Mozart's

pupil, Madame Therese von

Trattner, the wife of Mozart's

landlord at that time. The

title was “Fantaisie et Sonate

Pour le Forte-Piano [...]

Œuvre XI”.

The Fantasie probably

represents the kind of bold

improvisation with which

Mozart used to hold his

audiences enthralled, and

which, in its advanced

structure, daring modulations

and dramatic force, looks

forward to Beethoven. Its use

of C minor recalls other

stirring music in this key -

the Serenade for wind band (K.

388), later transcribed by

Mozart for string quintet in

1787 (K. 406), and, most of

all, the piano concerto, K.

491. The very opening of the

ensuing Sonata (K. 457) might

have been the dashing sally of

a grand concerto or symphony

in C minor, that key which,

since Beethoven's Fifth

Symphony, has been generally

regarded as being of

especially fateful moment.

Minuet in D major, K. 355

(576b)

There is an interesting

anecdote found in Rudiments

of Thorough Bass by

William Shield, London 1815,

where this Minuet - without

Trio - was published in full.

Shield notes “The above

Composition and anecdote were

presented to me by an

estimable brother Professor,

whose merit and truth have

cemented Gratitude and

Friendship. I have therefore

published them with confidence.”

The anecdote is as follows:

“To the honour of that great

Musician,who has produced so

many of the modern Composer's

archetypes, it should be

mentioned, that he was as much

entitled to esteem, for

Benevolence, as admiration for

his Genius; He had as our

immortal Bard expresses it, 'A

tear for pity, and a hand open

as the day, for melting

Charity', but unhappily that

want of prudence, and

attention, to the painful

minuteness of necessary

economy, often deprived him of

power, to indulge the feelings

of his Heart, by administering

to the appeals of misfortune.

A singular incident of this

nature, occurred to him, as

follows: As he was walking one

day, near the suburbs of

Vienna, he was accosted by a

Mendicant, of a very

prepossessing appearance, and

manner, who told his tale of

woe,with such effect, as to

interest M. strongly in his

favour; But the state of his

purse, not being correspondent

with the impulse of humanity,

he desired the Applicant to

follow him to a Coffee House.

As soon as they entered the

House, M. drew some music

paper from his pocket, and in

a few minutes composed the

Menuet, which is annexed to

this Memoir, which with a

Letter, from himself, he gave

to the distressed Man,

desiring him to take them to

his Publisher, who resided in

the City. A Composition from

M. was a Bill payable at

sight, and the happy Beggar

was immediately presented in

return for the MS. to his

great surprize, with five

Double Ducats.”

- This short but pungently

cromatic Minuet has lang

occupied a place of special

affection among lovers of the

composer, as has:

Rondo in D major, K. 485

This celebrated piece was

signed and dated at the end of

the autograph “Mozart mpr. le

10 de janvier 1786 à Vienne.”,

when the composer was in the

middle of his opera Le

nozze di Figaro

(completed on April 29, 1786).

Mozart composed the rondo for

his friend and Masonic brother

Franz Anton Hoffmeister who

published it in Vienna the

very same year. The dedication

to Countess Würben on the

autograph has been erased and

is no longer legible. Although

Hoffmeister entitled his first

edition “Rondo très facile”,

it is not all that simple and

is indeed a composition of

great sophistication. The

theme was taken from a work by

J. C. Bach, who had recently

(1782) died in London and had

been much admired by Mozart.

Some of Bach`s easy and

elegant style seems to have

entered this delightful music.

Sonata in F major, K.

533

Rondo in F major, K.

494

Mozart wrote this beautiful

and superior Sonata backwards:

he first wrote the Finale,

which he entitled in his

thematic catalogue “Ein

kleines Rondo für das Klavier

allein” (K. 494), i.e. a small

rondo for solo piano. It was

probably intended to form part

of a cycle of rondo movements

for piano, of which the two

others were K. 485 in D major

and K. 511 in A minor. K. 494

was, however, published

separately, by Philipp

Heinrich Bossler in Speyer in

1787. Then, under the date

January 3, 1788, Mozart

entered the first two movements

of the Sonata in his catalogue

as “Ein Allegro und Andante

für das Klavier allein”; he

then attached the previous

rondo and published all three

with Hoffmeister in the early

part of 1788. In the process

Mozart rewrote the Finale,

adding bars 143-169, a kind of

cadenza. Despite the

chronological differences

between the beginning and the

end of the work, Mozart

succeeded in creating a unified

whole of great beauty and

charm. The first movement bears

chains of legato slurs, so

that the opening theme might

even sound like a

transcription of a string

piece: against this undulating

pattern, Mozart brilliantly

sets off cascading eighth-note

triplets which dominate most

of the second part of the

exposition. And notice how

these two widely disparate

elements are artfully combined

in the development section.

There is both infinite repose

(the beginning) and infinite

movement (those many

descending arpeggios in

sixteenth notes) in the

Andante, where there are again

no dynamic marks whatsoever in

the first edition. And the

Rondo is, like its partners in

D major and A minor, of an

amazingly subtle construction

- that which in

eighteenth-century French used

to be called “une facture

étonnante” - down to the

surprise ending of pianissimo.

Fantasie in D minor, K. 397

(385g)

This impressive and sombre

Fantasie, the autograph of

which is no longer extant,

seems to have been written in

about 1782 and first published

(posthumously) in 1804, with,

however, the last ten bars as

we know them missing. The

traditional ending comes from

the Breitkopf & Härtel

edition of 1806. This was

apparently the kind of

improvisation for which Mozart

was so famous, and it is

fortunate that we have it and

K. 475 as a kind of witness to

this lost Mozartian tradition.

Rondo in A minor, K. 511

This extraordinary piece was

completed, as the autograph

attests, “Rondò di W. A.

Mozart li 11 Marzo1787”. It

was announced by Hoffmeister

for August 1786, but

publication was delayed until

April 1787, - in other words,

Mozart was late to finish the

commission.

Sonata in C major, K. 545

Mozart entered this work under

the date June 26, 1788 in his

catalogue with the

description, “Eine kleine

Klavier Sonate für anfänger” -

a small piano sonata for

beginners, which later became

known as the “Sonata facile”

when it was posthumously

published by the Bureau des

Arts et d'lndustrie in Vienna

in 1805. As in many such

teaching works, there are no

dynamic marks in the first

edition (nor were there any in

the comparable work by

Beethoven published in Vienna

that very same year: the

Sonatas Op. 49 No. 1 and

especially No. 2, intended for

the same grade of pupil).

This is a deceptively simple

sonata, but one of

incomparable mastery. Looking

forward to Schubert, the

recapitulation of the first

movement begins in the

subdominant (F major), so that

the home key is not

established until the entry of

the second subject. It would

have been an interesting topic

of conversation with a very

young but eager pupil. Nor is

the gravely beautiful Andante

a mere teaching exercise,

though it is clear that Mozart

wanted his pupil to learn a

supple manner of execution for

the so-called Alberti-bass

patterns which persist almost

throughout. The Finale is

rather like a Haydn rondo, and

the similarity extends to a

typically Haydnesque brevity

of thought and deed.

Adagio in B minor, K. 540

Entered into Mozart's

autograph thematic catalogue

as “Ein Adagio für das Klavier

allein, in H mol.” and dated

March 19, 1788, this deeply

felt and rather improvisatory

work is, as stated above, one

of the witnesses to the

composers profound depression

of 1788.It was published the

same year by Hoffmeister.

Nothing is otherwise known

about the origin of this bleak

Adagio - why and for whom was

it composed?

Sonata in B flat major, K.

570

This sonata was entered into

Mozart's own catalogue of

works as having been composed

in the month of February

1789. It is there entitled

“Eine Sonate auf Klavier

allein”, i. e. for piano solo,

which makes it astonishing

that the first edition, which

Artaria & Co. in Vienna

issued posthumously in 1796,

contained a violin part as

well. Nowadays this violin

part is regarded as spurious.

There is no mention of this

popular sonata in Mozart`s

correspondence, and we have no

idea why it was written -

presumably for a fairly

advanced piano pupil, for the

music is by no means easy of

execution. The autograph

manuscript for the first

movement has survived (British

Library, London), but not the

other two movements, for the

textual accuracy of which we

are dependent on the first

edition by Artaria (supra).

It is curious that in this

first edition there are

.tbsolutely no dynamic marks

whatsoever in the last two

movements except for a final

piano (bar 85) and forte

(last bar) of the Finale.

The tempo marking “Adagio” for

the slow movement, so rare in

Mozart (compared, for example,

to Haydn), shows that an

especially serious and grave

music tnay be expected: the

characteristically Mozartian

chromatic lines take on a

curious poignancy here. The

Finale has an oblique kind of

force, especially in the

section at bars 45ff where the

right hand has repeated

quavers (later in the left

hand): the music is almost

like one of the rugged

symphonies which Viennese

composers were writing in the

1770s. But there is,

throughout this sonata, a

certain kind of impersonality

which we find in other works

of this bleak period in

Mozart`s life - 1789 and 1790.

We may surely assume that he

took this work on tour when he

visited Prague, Dresden,

Berlin and Leipzig later in

the year 1789 - a largely

unsuccessful visit,

financially.

Sonata in D major, K. 576

When he visited Berlin and

Potsdam in 1789, Mozart seems

to have agreed to compose

three string quartets for the

King, Friedrich Wilhelm II,

who was a good amateur

cellist, and six easy sonatas

for the royal daughter,

Princess Friederike of

Prussia. Mozart completed the

three quarters and refers to

the six sonatas in a letter to

his fellow Mason, Michael

Puchberg, on July 12-14, 1789,

but in the event he completed

only one of the sonatas, that

in D major, K. 576, which he

entered in his thematic

catalogue as “im Iullius. Eine

Sonate auf Klavier allein”. It

turned out to be Mozart's

final piano sonata.

The sonata has always been a

popular work. It was not

published until 1805 but

immediately became one of his

best loved works for the

piano. It is obviously

composed in a light and

popular style, as indeed the

string quartets for Prussia

were composed in quite a

different manner from those he

had written for Haydn in the

early 1780s. In this respect,

there is a certain similarity

between the “easy” style of

Mozart's “Coronation” Concerto

in D major, K. 537, and the

Sonata in the same key. He had

come a long way from the

agonized personal language of

the C minor Concerto for

piano, K. 491, and the

Fantasie and Sonata in the

same key (K. 475 and K. 457).

It was not until 1791 that he

was able to reconcile the

popular and the learned with

such works as the Clarinet

Concerto, Ave verum corpus

and the last two operas (The

Magic Flute and La

clemenza di Tito).

Fantasie in C minor, K. 396

(385f)

This moody and dark-hued work

began life in about 1782 as

the beginning (Adagio) of a

sonata for piano and violin.

Mozart's autograph, once owned

by Goethe, is now in the

Goethe and Schiller Archives

in Weimar. The fragment stops

at the double bar, and after

Mozart's death it was

completed for piano solo by

Maximilian Stadler and

published by Jean (Giovanni)

Cappi in 1802 as “Fantaisie

pour le Clavecin ou Pianoforte

dediée à Mad. Constanze

Mozart.” It has always been

regarded as a striking example

of Mozart's early Viennese

years - bold, original and

concise even though the

technique is clearly

improvisatory.

©

1993 H. C. Robbins

Landon

The Clarke Fortepiano

No. 17

(Collection

Immerseel-Chevallier)

In his Nuova invenziane,

published in 1711, Scipione

Maffei maintained that, since

the technique required for

playing the fortepiano was

different from that used with

earlier keyboard instruments,

it was therefore necessary to

adopt a new method of

fingering. The new sound

producer, the hammer, did

indeed greatly increase the

expressive possibilities

available to the pianist, but

it also gave instrument makers

and players alike a few

headaches when they attempted

to put these new possibilities

into practice. For instance,

when the tension is relatively

low, the hammer must activate

the string without, however,

acting as a damper, something

which is only possible with an

extremely fast, rotating

finger movement. With his

Viennese, check-rail action,

Anton Walter (1752-1826)

succeeded in getting the

string to vibrate more freely.

Further advantages of the

Walter action lay in its

offering the pianist greater

scope for dynamic

differentiation, in making it

easier for him to perform

arpeggios, and in improving

the inclusion of the resonance

register. And as the player,

on attack, only needed to

depress the key a very short

way, he found he had a wholly

new range of possibilities for

introducing embellishments

into his “musical speech”. The

difference between legato

and staccato could be

brought out more clearly than

on other keyboard instruments

and the richer sonority as

well as new tonal registers

made up a whole world of

expressive possibilities that

had been hitherto unknown.

When properly played, the

fortepiano of Walter`s design

is ideally suited to

performance in smaller halls,

though, even in larger venues,

the sound it produces carries

well. It is also an instrument

that is eminently suitable for

accompanying lieder in

intimate surroundings, yet

equally capable of sustaining

a dialogue with an orchestra,

as Mozart knew from his Akademien

(concerts). And it was

precisely this versatility

that Mozart valued so highly,

a fact which no doubt

encouraged him to write no

fewer than 21 solo concertos,

a great deal of chamber music

with piano,a large number of

sonatas and other piano pieces

for two and four hands.

Mozart's Walter pianoforte,

which at that time represented

the very latest in the art of

piano-building, must have

given the composer a great

deal of pleasure, just as

Christopher Clarke's superb

reproduction gives me pleasure

today, too.

Clarke, the most famous

pianoforte-builder of today,

built this wonderful

instrument in 1988, specially

for the performance of the

complete Mozart pianoforte

concertos with the orchestra

“Anima Eterna” during the

1990-91 season.

Christopher Clarke`s

commentary in 1988: “The

instrument is based on the

example conserved in the

Germanisches National-Museum,

Nuremberg (MINe 109),with

additional data collated from

several other Walter

instruments of the same period

in public and private

collections. The frame of fir,

oak and sycamore, is built

with dovetail joints at cheek

and tailboard: the belly rail

is mortised into the spine.

The bentside is built up

according to Walter's special

system, a laminated rim

supported by hardwood forks

mortised into the

bottomboards.The soundboard,

of selected Swiss spruce, is

accurately thicknessed and

ribbed in conformity to the

original. The strings, other

than in the bass, are of iron,

which gives the proper balance

of harmonics (steel strings

are too rich in high

harmonics, giving an 'edgy'

sound). The action is

accurately copied from

Walter's, using identical

materials and construction

throughout. Walter introduced

the use of low-friction metal

Kapseln (the forks in

which the hammers pivot) and a

check rail to catch the

hammers after they have struck

the strings. This produced an

action of much greater dynamic

range and faster repetition

than its predecessors. Walter

exploited these advances

further by placing a heavier

bridge on the soundboard and

increasing the string tension.

The result was a fuller, more

powerful sonority which opened

up new possibilities to

composers of the late 18th

century. The hammers are

covered with antelope leather,

and the dampers are also

covered with soft deer and elk

leather, as on the original

instrument. The use of leather

for the dampers is almost as

important as its use for the

hammers in the production of a

characteristic sound: the

ending of a tone is as

important as the beginning.

The keyboard, the 'point of

entry' to the instrument, is

in ebony and bone, copied

minutely from Walter's. The

compass of the instrument is 5

octaves and two keys (FF-g'").

The length is 221 cm with lid,

the width 102 cm with lid the

height of the case 28 cm with

lid and the overall height is

83 cm with lid. The weight is

approximately 70 kg.

“My overall aim was to provide

the player with an instrument

which differs from a genuine

Walter only in its age and in

the name above the keyboard.

This aim is pursued to the

smallest detail,

constructional or visual, in

the hope of providing a

coherent impression of meeting

a fortepiano fresh from an

18th -century Viennese

workshop, and of building an

instrument as robust as its

200-year-old forebears.”

Jos

van Immerseel /

©1988 Christopher Clarke

|

|

|