|

|

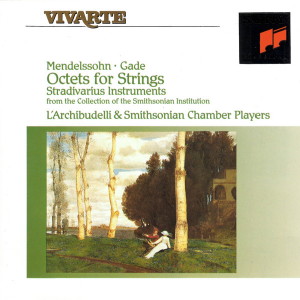

1 CD -

SK 48 307 - (p) 1992

|

|

VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 36

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Octets for String |

|

59' 05" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Felix MENDELSSOHN

BARTHOLDY (1809-1847) |

|

|

|

| Octet

for 4 Violins, 2 Violas and 2

Violoncellos in E flat major, Op. 20 |

|

30' 09" |

|

| - Allegro

moderato, ma con fuoco |

13' 05" |

|

1

|

| -

Andante |

6' 36" |

|

2 |

| -

Scherzo. Allegro leggierissimo |

4' 55" |

|

3 |

| -

Presto |

5' 33" |

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

| Niels Wilhelm GADE

(1817-1890) |

|

|

|

| Octet

for 4 Violins, 2 Violas and 2

Violoncellos in F major, Op. 17 |

|

28' 34" |

|

| -

Allegro molto e con fuoco |

9' 23" |

|

5 |

| -

Andantino quasi Allegretto |

6' 23" |

|

6 |

| -

Scherzo. Allegro moderato e

tranquillo |

3' 49" |

|

7 |

| -

Finale. Allegro vivace |

8' 59" |

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

L'Archibudelli &

Smithsonian Chamber Players

|

|

| - Vera Beths, violin

I (Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1687 the Ole

Bull, Smithsonian) |

|

| - Jody Gatwood, violin

II (Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1727,

Private collection) |

|

| - Lisa Rautenberg, violin

III ( Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1709

the Greffuhle, Smithsonian) |

|

| - Gijs Beths, violin

IV (Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1734, the

Hellier, Private collection) |

|

| - Steven Dann, viola

I (Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1695, the

Herbert Axelrod, Smithsonian) |

|

| - David Cerutti, viola

II (Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1690, the

Medici, Library of Congress) |

|

| - Anner Bylsma, cello

I (Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1701, the

Servais, Smithsonian) |

|

| - Kenneth Slowik, cello

II (Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1688, the

Marylebone, Smithsonian) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

American

Academy of Arts and Letters, New

York (USA) - 26/28 January 1992 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Peter

Laenger (Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 48 307 - (1 CD) -

durata 59' 05" - (p) 1992 - DDD |

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Frühlings-stimmung

by Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901)

- Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte,

Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

It

is astonishing that

Mendelssohn's Octet was

written by a boy of sixteen,

not because juvenile

compositions are so rare, but

achievements of both personal

character and artistic

technique are so evident in

the piece that it would be a

great accomplishment for a man

of any age. Mozart, even more

celebrated for his musical

precocity than Mendelssohn,

composed at an earlier age,

but produced nothing by his

teens that bears the stamp of

such maturity and originality

as this Octet. Moreover,

notwithstanding the common

prcjudice that early mastery

breeds facile and superficial

working methods, Mendelssohn

was a fastidious reviser of

his own works even from the

time of the Octet, which he

finished in 1825 but waited

for seven years to publish.

(His more famous “Italian”

Symphony never pleased him and

remained in manuscript at the

time of his death.)

Felix Mendelssohn was born in

1809 in well-to-do

circumstances, but under the

somewhat austere parental

guidance of his father,

Abraham, a wealthy banker

whose unenviable fate was to

live in the shadow not only of

his more illustrious son but

of his own famous father,

Moses, an acclaimed

philosopher. While the family

fortune made it possible for

the young Felix to conduct his

compositions in performances

by a small orchestra assembled

by his father, his upbringing

was strict; and beyond the

driven temperament with which

his father dominated the

Mendelssohns' domestic life,

there was the social pressure

of anti-semitism that

persuaded Abraham to renounce

Judaism and adopt Christianity

for the security of the

family. According to a recent

biographer, Eric Werner, this

led to a conflict between

father and son when Abraham

attempted to suppress the

Mendelssohn name entirely in

favor of the adopted name

Bartholdy, to which Felix

never consented. Eduard

Devrient, writing in 1869,

recalled Abraham's

“contentious disposition”

which became “at last

intolerable”. Unlike Werner,

however, Devrient attributed

this to “physical causes”, and

wondered: “Had this excessive

irritability anything to do

with his sudden death [in

1835], and was it to descend

upon Felix?”

The year 1825 saw three

significant events in the life

of the sixteen-year-old

Mendelssohn. The first was a

trip to Paris during which

Abraham introduced his son to

the aging and cantankerous

Luigi Cherubini, whose

favorable judgement of the

young musician seems to have

surprised almost everyone

except perhaps Felix himself,

preoccupied as he was with his

own disdainful criticism of

musicians and musical life in

Paris (even comparing

Cherubini to “an extinct

volcano”). The second was the

move in Berlin of the

Mendelssohns to their palatial

residence in Leipzigerstrasse,

the family home until Felix's

death at 38 in 1847. The third

was the completion in October

of the Octet, which he

dedicated to his friend and

violin teacher, Eduard Rietz

(1802-1832). It was Rietz who

made the copy of Bach's St.

Matthew Passion that was

presented to Felix two years

earlier and later played such

an important part in

Mendelssohn's revival of

Bach's music.

Mendelssohn attached special

importance to the scherzo. His

sister, Fanny, wrote: “To me

alone he told his idea: the

whole piece is to be played staccato

and pianissímo, the

tremulandos coming in now and

then, the trills passing away

with the quickness of

lightning; everything new and

strange, and at the same time

most insinuating and pleasing,

one feels so near the world of

spirits, carried away in the

air, half inclined to snatch

up a broomstick and follow the

aerial procession. At the end

the first violin takes a flight

with a leather-like lightness,

and - all has vanished.”

The idea is supposed to have

originated in these lines from

Goethe's Faust

describing Walpurgis Night

(Pt. 1, l. 4395-98), a subject

to which the composer would

later return for his great

secular oratorio Die erste

Walpurgisnacht, inspired

by and set to another poem

also by Goethe: “Wolkenzug und

Nebelflor / Erhellen sich von

oben. / Luft im Laub, und Wind

im Rohr,/ Und alles ist

zerstoben.” (Drifting cloud

and gauzy mist / Brighten and

dissever. / Breeze on the leaf

and wind in the feeds / And

all is gone forever.

Translation: © 1951 Louis

McNiece).

The scherzo is the only

movement of the Octet that

Mendelssohn did not revise for

publication. In 1829, he

substituted an orchestral

arrangement of it for the

menuet in a performance of his

First Symphony, but this

arrangement of the movement

was not published until 1911.

The orchestral nature of the

entire work has often been

noted. Louis Spohr wrote in

his autobiography: “My four

double quartets [...] remain

the only ones of their kind.

An octet for stringed

instruments by Mendelssohn-

Bartholdy belongs to quite

another kind of art, in which

the two quartets do not

consort and interchange in

double choir, with each other,

but all eight instruments work

together.” The most important

statement on the nature of the

instrumentation, however, is

by Mendelssohn himself. His

advice to the performers

appears on the first page of

each part: “This octet must be

played in the style of a

symphony in all parts; the pianos

and fortes must be

very precisely differentiated

and be more sharply

accentuated than is ordinarily

done in pieces of this type."

For those who feel this

statement justifies

performance of the Octet by a

string orchestra, it should be

pointed out that the composer

would hardly have thought it

necessary to advise members of

a string orchestra to play “in

the style of a symphony”. It

remains a unique and original

work without precedent, and

followed up only by a few

subsequent essays of composers

willing to risk comparison

with its sublime

accomplishment.

The Danish composer Niels

Gade is usually

remembered today in connection

with Mendelssohn, although

Gade's music reveals not only

other influences, notably

Schumann's, but a personal

style that is evident in his

earliest surviving works.

Nevertheless, Gade's Octet

(1848) is the composition in

which his debt to a

Mendelssohnian model is

probably most obvious. The

instrumentation and formal

plan that his piece shares

with Mendelssohn's masterwork

make Gade's Octet, even in the

absence of a dedication, an

homage, yet it is not that of

a youthful imitator but of a

mature artist with important

and highly individual

compositions behind him. His Ossian

Overture (1840) and his First

Symphony (1842) are both works

of a strong, lyrical character

by a composer who has found

his own voice. Gade sent his

First Symphony to Mendelssohn

after it had been rejected for

performance in Leipzig, and

its success led to Gade's

journey there.

Why did Gade compose his

Octet? 1848 was a decisive

year for him. After his close

association with Mendelssohn

from 1844 until the latter's

death in 1847, he succeeded

him as conductor of the

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

and might have had a brilliant

career in one of Europe`s

great musical centers.Yet he

wished to build in Copenhagen

a musical establishment like

the one he had found in

Leipzig. Spurred on, no doubt,

by the outbreak of the

Schleswig-Holstein war between

Prussia and Denmark, he

returned early in 1848 to

Copenhagen where he remained

for the rest of his life.

Certainly, Mendelssohn'”s

influence not only as a

composer, but as a cultural

statesman of such widely

ranging musical interests as

education and the working

condition of musicians played

a major part in Gade”'s own

future direction in

Copenhagen, where, for the

next four decades, he would

exert a critical influence on

all aspects of Denmark'”s

musical life. It is hardly

surprising that in the year he

undertook to emulate the

administrative accomplishments

of Mendelssohn's Leipzig

period in his homeland, Gade

should also set to work on a

composition which was to

exhibit so thoroughly the

virtues of his great mentor.

©

1992 Jan Newsom

ON THE

INSTRUMENTS

Washington, D. C. enjoys many

cultural advantages as the

capital of the United States,

among them the largest museum

complex (the Smithsonian

Institution) and the largest

research library (the Library

of Congress) in existence,

plus an enviable array of art

museums, including the

National Gallery and the

Corcoran Gallery of Art. In no

other city are more

Stradivarius instruments

housed in publicly accessible

institutions than in the

District of Columbia. The

Corcoran Gallery possesses a

fine quartet of Strads, the

Smithsonian holds a quintet

with two cellos, and the

Library of Congress boasts no

fewer than six Stradivari

instruments. In addition,

several Washington residents

own Stradivari violins, making

the ratio of

Strads-to-inhabitants higher

in the U. S. capital than in

any other city. Washington's

selection of Strads is

impressive not only in

quantity, but in quality as

well. Of the roughly 650

Stradivarius instruments that

survive from the eight to

eleven hundred he is thought

to have made during his long

and productive life

(1644-1737), only thirteen are

violas: four of these are

housed in Washington. Four of

the eleven extant decorated

instruments from Stradivari's

hand are to be found in

Washington. Finally, the

Library of Congress and the

Smithsonian possess two

large-model Strad cellos which

belong among the small

handfull of such instruments

which have retained their

original size.

The core group of instruments

heard on this recording is

made up of those held by the

Smithsonian's National Museum

of American History. The

magnificent Servais

cello, donated to the Museum

in 1981 by Charlotte Bergen, a

wealthy amateur who had

acquired the instrument in

1929, has frequently been

described as “one of the

supreme works of the master”.

Built in 1701, it was

apparently the last of the

large-model bass instruments (bassetti)

Stradivari designed before

turning, in 1707, to the

smaller (and therefore easier

to play) model to which he

subsequently adhered.

Beginning in the 19th century

(and lamentably continuing

well up to the present day),

most of these large cellos

were cut down in a Procrustean

effort to make them conform to

the post-1707 Stradivarian

standard. This operation

involved removal of a fair

amount of wood, shortening the

instrument by 3-4 cm. The Servais

and its Library of Congress

counterpart, the 1697 Castelbarco,

are among a select few

Stradivarius cellos to survive

in their original, uncut

grandeur. The unparalleled

resonance of the Servais

was made justly famous by the

Belgian virtuoso Adrien

François Servais, who owned

the instrument from the late

1840s until his death in 1866.

The Greffuhle and Ole

Bull violins of the

Stradivarius quartet placed on

loan to the Smithsonian in

1986 by Dr. Herbert R. Axelrod

are decorated with wide

perimeter banding of ivory

marqueterie lozenges and

pastilles, and inlaid foliate

designs covering the surfaces

of the ribs and the sides and

back of the scroll. The viola,

rediscovered in 1931 after

disappearing from collectors'

circles for nearly a century,

bears much more subdued

decoration limited to an

inscribed coat-of-arms now

partially hidden by the

fingerboard, and a double row

of purfling which may date

from the time at which this

instrument, originally

constructed as a large tenore,

was reduced to its present

size. The Marylebone

cello, which predates the Servais,

was originally of similarly

large dimensions, but was cut

down during the course of the

1800s. Comparison of the tone

of the deeper-voiced Servais

with the tenorlike Marylebone

is particularly interesting in

the context of the two octets

presented here, as the

difference makes the two

instruments a splendid tandem

for carrying out their

respective roles.

For this recording, the

Library of Congress

contributed the viola, known

as the Medici, which may have

been built to provide the

third voice in the quintet of

instruments Stradivari made

for the Grand Duke of Tuscany,

Cosimo Medici III, in 1690.

(Its rather larger

counterpart, the Tuscan

tenor, is to be found in the

collection of the Cherubini

Institute in Florence.) The Hellier

violin, purchased directly

from the maker himself by Sir

Samuel Hellier in 1734 (and

thus one of the few

instruments whose provenance

is completely documented), was

the second ornamented violin

made by Stradivari. Like the

1727 violin that completes our

octet of instruments, it was

made available for use in this

project through a private

collectoris generosity.

All eight instruments were

strung for this recording in

gut, producing a sound that is

richer yet less penetrating

than the same instruments

yield when adjusted for the

higher tension associated with

the metal strings in common

use since the middle third of

the 1900s, and encouraging the

performers to explore the

outer boundaries of the

instruments' dynamic ranges,

while using vibrato

selectively rather than

continuously. The crystalline

clarity of the famed

Stradivarian tone illuminates

the complexities of octet

writing particularly well,

sharply etching each line of

the ingenious and complicated

textures.

©

1992 Kenneth Slowik

|

|

|