|

1 CD -

SK 53 982 - (p) 1994

|

|

VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 44

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

String Quartet &

Trios

|

|

63' 51" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Franz SCHUBERT

(1797-1828) |

|

|

|

| String

Quartet in E flat major, D 87 |

|

26' 08" |

|

| - Allegro più

moderato |

9' 59" |

|

1

|

| -

Scherzo. Prestissimo - Trio |

2' 26" |

|

2 |

| -

Adagio |

5' 45" |

|

3 |

| -

Allegro |

7' 58" |

|

4 |

| String

Trio in B flat major, D 471

(fragment) |

|

16' 12" |

|

| -

Allegro |

10' 49" |

|

5 |

| -

Andante sostenuto |

5' 23" |

|

6 |

| String

Trio in B flat major, D 581 (second

version) |

|

21' 11" |

|

| - Allegro moderato |

5' 40" |

|

7 |

| -

Andante |

5' 28" |

|

8 |

| -

Menuetto. Allegretto - Trio |

3' 36" |

|

9 |

| -

Rondo. Allegretto |

6' 27" |

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

| L'Archibudelli |

|

| - Vera Beths, violin

I (Jacob Stainer, Absam, Tyrol, 1649) |

|

| - Lucy van Dael, violin

II (Nicolo amati, Cremona, 1643) |

|

| - Jürgen Kussmaul, viola

(William Forster, London, 1785) |

|

| - Anner Bylsma, cello

(Matteo Goffriller, Venice, ca. 1690-1699) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Schloß

Grafenegg, Reitschule (Austria) -

8/9 June 1993 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 53 982 - (1 CD) -

durata 63' 51" - (p) 1994 - DDD |

|

|

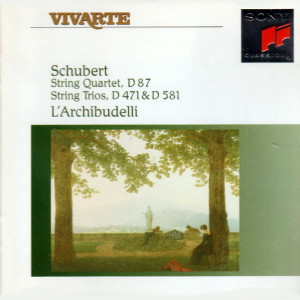

Cover Art

|

|

Gartenterrasse

by Caspar David Friedrich

(1774-1840) - Photo: Archiv für

Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Chamber

Music by Young Schubert

The chamber

works included in the present

recording were all written

before or at the beginning of

the period of upheaval in

Schubert's life when he

succeeded in breaking away

from his formal models and

going his own creative way. In

other words, they are early

works that predate the period

1817-1822 and vouchsafe an

insight into the composer's

musical origins.

Of his youthful string

quartets from the years

between 1812 and 1816, the

String Quartet in E flat major

of November 1813 occupies a

central position not only

chronologically but also in

terms of its formal design.

Schubert's tendency to merge

formal sections by means of

monothematic structures is

already on the decline here.

None the less, he still

dispenses with overtly

contrastive thematic elements

in the opening movement and

attempts instead to generate

tension by means of

occasionally grandiose

gestures. A similar sense of

balance is also found in the

slow movement, which forgoes

the usual contrastive middle

section. The relatively

dance-like Andante movements

of the earlier quartets are

replaced here, for the first

time in Schubert's writing for

the medium, by an Adagio. That

the young composer was

perfectly capable of

transcending traditional form

in his handling of the

different types of movement

and of creating textures of

filigree delicacy is clear from

the Scherzo and final movement,

both of which are doininated

by seemingly weightless

melodic lines coupled with

equally airy, fleet-footed

writing in the accompanying

voices. In the Scherzo this

melodic vein is impressively

overshadowed by the C minor

dance of the Trio and

interrupted in the Finale by

the serenade- like tone of the

second subject. The almost

orchestral bravura manner that

typifies this Finale - a manner

as clearly intentional as it

is masterly - may suggest the

importance this work must have

had for its sixteen-year-old

composer: a relatively restful

diversion intended for the

circle of music lovers who

frequented his parents' house,

with links with the recently

completed First Symphony, but

inspired, more especially, by

his attempts to write his first

fully worked-out opera, Des

Teufels Lustschloß,

which was to preoccupy him now

and during the months ahead,

while he was training to

become a primary-school

teacher.

Schubert's contribution to the

medium of the string trio is

limited to two works, of which

the first was to remain a

fragment. Work on both of them

(September 1816 and September

1817 respectively) coincided

with a particularly productive

phase in his creative output,

when he was concentrating on

lieder, operas, masses and

also instrumental music. Why

he should have turned his

attention to string trios at

all at this time is hard to

say and based for the most

part on speculation.

One thing, at least, is clear

(and this is a point that

Schubert shares with most of

his predecessors and

contemporaries), namely, that

he preferred writing string

quartets, not least as a

compositional exercise, even

though he wrote noticeably

fewer such works at the time

he was working on his trios.

The period of upheaval

mentioned in the opening

paragraph had already begun by

now, and from this point of

view the string trios may

perhaps be regarded as

attempts at reorientation.

What is striking about both of

them is their backward-looking

tendency and almost

rococo-like delicacy,

notwithstanding their

otherwise traditional design.

Such an attitude has left its

mark not only on the clarity

of Schubert's handling of

first-movement sonata form, the

motivic and tonal distinction

between the modulatory middle

sections and the often simple

periodicity in the structuring

of the themes; equally

characteristic is the nature

of the ornamental writing in

varied sections within the

movements or in densely figured

final phrases. It seems almost

as though Schubert had wanted

to follow an existing formal

design in broaching the genre,

rather than attempt to invest

that form with new and

idiosyncratic ideas.

External influences may also

have played a part here.

According to a report by

Schubert's friend Leopold von

Sonnleithner, the group of

amateur musicians that met at

Schubert`s parents' house

around 1814 often played

Haydn's Baryton Trios, and the

charm and melodiousness of

these jewel-like pieces may

well have drawn the nineteen-

and twenty-year-old composer

into their creative sway,

although the striking

similarities in the figural

writing and handling of the

individual voices are no doubt

due to the general problems of

writing for three string

instruments. In order to avoid

excessive multiple stopping,

the composer often seeks

salvation in luxuriantly

playing around with the melody

or in arpeggio passages, both

typical features of numerous

earlier examples of the string

trio as a genre.

It is also conceivable that

both Trios were written for

private concerts that were

held regularly every winter

from 1816 onwards at the home

of Leopold von Sonnleithner`s

parents. (The fact that both

works were written in the

month of September would

certainly lend support to this

suggestion.)

It is impossible, however, to

define the origins and aims of

these works any more

precisely. Still less can we

be certain why Schubert broke

off work on the first of the

Trios in the middle of the

second movement, at a point

where, thirty-nine bars into

it, a central section based on

different melodic material

would have followed had he

adopted the model of the

second Trio.

We may be on safer ground in

assuming a concrete reason for

his writing the second Trio,

of which there are in fact two

surviving versions. The first

version exists only in the

form of a full score, the

three parts of which Schubert

then proceeded to write out

again, radically changing a

number of details and thereby

producing the second version.

In short, we are dealing with

two stages in the same

compositional process. All

such changes affect imbalances

in the first version. The end

of the first movement, for

example, has been rewritten in

such a way that the original

breakneck demisemiquavers have

been turned into more

manageable semiquavers, while

the bridge passages, which had

previously involved

over-abrupt changes in harmony

and figuration, have been

extended in length. This

polishing process also

involved numerous other

details of articulation and

dynamics, with the result that

the second version (as

recorded here) is palpably

superior to the first.

Werner

Aderhold

(Translation:

© 1994 Stewart Spencer)

|

|

|