|

1 CD -

SK 53 965 - (p) 1993

|

|

VIVARTE - 60

CD Collection Vol. 2 - CD 47

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Harmoniemusik |

|

70' 39" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Harmoniemusik on Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart's "Le nozze di Figaro" |

|

|

|

| Arr.

Georg Sartorius, c. 1800 - for 2

clarinets, 2 horns, 2 bassoons (&

double bass) |

|

17' 50" |

|

| - Sinfonia |

4' 05" |

|

1

|

| -

Duettino. Allegro |

2' 50" |

|

2 |

| -

Duettino. Allegro |

2' 40" |

|

3 |

| -

Se vuol ballare signor Contino |

2' 34" |

|

4 |

| -

Non più andrai |

2' 56" |

|

5 |

| -

Terzetto. Allegro di molto: Susanna

or via sortite |

2' 45" |

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

| Gioachino ROSSINI

(1792-1868) |

|

|

|

| Harmoniemusik

(Quintet) in F major - for 2

clarinets, 2 horns, bassoon (& double

bass) |

|

13' 38" |

|

| - Andante ·

Allegretto |

4' 43" |

|

7 |

| - Allegretto |

1' 48" |

|

8 |

| - Adagio |

2' 14" |

|

9 |

| - Allegro |

1' 21" |

|

10 |

| - Polacco · Trio |

3' 22" |

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

| Harmoniemusik on

Gioachino Rossini's "Il barbiere di

Siviglia" |

|

|

|

| Arr.

Wenzel Sedlak, c. 1820 - for 2

clarinets, 2 horns, 2 bassoons (&

double bass) |

|

36' 14" |

|

| - I. Ouverture.

Andante maestoso · Allegro vivace |

7' 17" |

|

12 |

| - II.

Introduzione. Moderato | III.

Vivace |

2' 01" |

|

13 |

| - IV. Cavatina |

V. Allegro |

4' 00" |

|

14 |

| - VI. Cavatina.

Allegro vivace |

2' 09" |

|

15 |

| - VII. Duetto.

Allegro maestoso · VIII. Allegro |

6' 56" |

|

16 |

| - IX. Cavatina.

Andante | X. Moderato |

4' 59" |

|

17 |

| - XI. Aria.

Allegro |

4' 44" |

|

18 |

| - XII. Duetto.

Allegro |

4' 05" |

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

| Mozzafiato |

|

- Charles Neidich,

clarinet

- Ayako Oshima, clarinet

- Dennis Godburn, bassoon

- Michael O'Donovan, bassoon

- William Purvis, natural

horn

- Stewart Rose, natural horn

- Marji Danilow, double bass

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

American

Academy of Arts & Letters, New

York (USA) - 1 February &

30/31 March 1993 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf

Erichson |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Stephan

Schellmann (Tritonus)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Sony

/ Vivarte - SK 53 965 - (1 CD) -

durata 70' 39" - (p) 1993 - DDD |

|

|

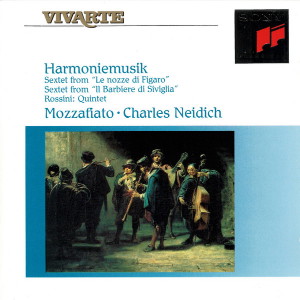

Cover Art

|

|

Serenade

"Barbier von Sevilla" by

Carl Spitzweg (1806-1885) - Photo:

Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte,

Berlin |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The

German word “Harmoniemusik”

means, simply, music played by

groups of wind instruments, or

Harmonien. A delightful

tradition of music-making by

such wind groups reaches back

at least several centuries

into the past, but only a

portion of it has been

documented by modern

scholarship. Perhaps for this

very reason we may enjoy all

the more the rediscovery of

this repertoire and the

instruments that best bring it

to life.

A striking feature of much Harmoniemusik

- especially when played on

historically appropriate

instruments - lies in its

evocation of certain

sonorities of the organ and

its modern derivatives such as

the harmonium, the harmonica,

or even the accordion. Roger

Hellyer (Grove 6th ed.VIII:

167-8) points out that Harmonien

instruments were usually

played in pairs, even where

there was only a single part.

These instruments were

predominantly reeds - oboes,

clarinets, bassoons - with

horns, occasionally flutes,

and some kind of bass

instrument. The resultant

sound was strikingly like that

produced by the reed and flute

combinations on the organ. The

relationship was intentional,

but it may be difficult to say

which was the model and which

the simulation. The early 17th

-century composer Michael

Praetorius devoted years to

describing the known

instruments and their history

in his Syntagma musicum

(1614-1620). Praetorius

emphasized the familial nature

of groups of wind and string

instruments, and his

comparison of those groups

(especially the wind groups)

to the organ ranks is

unmistakable. One important

aspect that Harmonien

shared with organs was the

ability to adapt to different

acoustical conditions and

needs. For example, given

enough “wind power”, both were

able to fill a room with

magnificent volume and clarity

of attack or, on the other

hand, to fill the same space

with an ethereal softness.

The usefulness of wind

instruments in a variety of

acoustical settings,

especially outdoors, has

always been a point in their

favor. But other useful

aspects include greater

mobility (compared, say, to

dragging around a cello and a

chair), and greater

imperviousness to atmospheric

conditions. The capability of

sheer loudness has gained the

winds a permanent place in

military engagements, festive

and otherwise, but a higher

resistance to the effects of

both sunlight and dampness

must also have gained the Harmonien

some superiority to their

stringed counterparts. But for

whatever reasons, practical or

aesthetic, the Harmonien

gained a place in numerous

European courts from the end

of the 17th century until

about the middle of the 19th

century. They ranged in size

from woodwind duos to sextets

and octets (with an occasional

double bass underneath) to

light military bands, and they

played diverse engagements

from weddings and funerals to

concerts, as well as ordinary

background music for dinner.

Despite the evidence of most

extant scores and parts, Harmonien

were not exclusively a feature

of the Austro-German culture;

they flourished in the courts

of England, France, Belgium,

Monaco, and other pockets of

cultural privilege. Likewise,

the repertoire for these

groups was diverse. Composers

for the English Harmonien,

for example, developed unique

military “divertimentos”,

while the French specialized

in operatic potpourris known

as pièce d'harmonie.

On this recording we hear two

German transcriptions of

Italian operatic airs and an

original composition by

Rossini specifically for wind

group. The transcriptions are

settings of numbers from the

“Figaro” operas of Mozart and

Rossini - not in potpourri

style, but each number

complete in itself. They were

made by two court

Kapellmeisters of the early

19th century, selfidentified on

the title pages as Georg

Sartorius,“Hochfürstlich

Hessen Darmstaedtischer Capell

Director” in Darmstadt, and

Wenzel Sedlak, “Fürst Johann

Liechtenstein'scher

Capellmeister” in Vienna. In

an age when musical copyrights

were unknown, such

exploitations of great works

were not only tolerated, but

were considered good

advertising for the original

composer as well.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, of

course, could not have lived

long enough to enjoy any

professional symbiosis offered

by Sartoriusis transcription.

Little is known about

Sartorius, but from the

title-page dedication of the

present work we can assume

that he fashioned it during

the reign of Ludwig X, first

Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt,

who ruled from 1790-1830 and

built the modern town of

Darmstadt. On the other hand,

Wenzel Sedlak's transcription

of numbers from The Barber

of Seville might easily

have benefitted the original

composer - depending on the

date, of course. Sedlak, a

well-known clarinettist, was

professionally active during

the heyday of Rossini. The

present transcription could

date from between 1816 (the

year of the premiere of Il

barbiere) and 1836 (with

the death of Sedlak”s patron,

Prince Johann Josef von

Liechtenstein) - but more

probably, according to actual

events, not later than from

1830.

The two transcriptions,

although likely intended for

similar occasions, show some

interesting differences. The

most significant of these

differences is that while the

Sedlak-Rossini transcription

retains the original keys of

the operatic numbers, every

number in the Sartorius-Mozart

transcription has been

transposed to suit the

relative compatibility of wind

instruments to the flat keys.

One might initially be tempted

to assume from this difference

that the Sartorius work,

considering its apparent

deference to fundamental

instrumental convenience, is

the earlier work - but this

assumption cannot be upheld.

One might as easily make the

opposite case - that in the

early stages of, say, clarinet

development, players kept on

hand for performances a

variety of instruments,

barrels, and mouth-pieces -

and that, in fact, a

restriction to flat keys might

indicate the more modern use

of fewer, or even single,

on-location instruments.

Both transcriptions offered

here share an incompleteness

favoring the earlier parts of

each opera. Mysteriously,

Sartorius limited his work to

the highlights of Act I of Le

nozze, and added only a

single piece from the middle

of Act II. We miss such

favorites as Cherubino's

arias,“Non so più” and “Voi

che sapete”, and the

Countess's great aria, “Dove

sono”.

The pieces in Sartorius's

score are not numbered, and it

is impossible to know if he

intended to continue the

transcription. The following

list shows the progress of his

work - played on this

recording with a “Mozartian”

substitution of a string bass

for the written contra-

bassoon part:

Overture

(in B flat, orig. in D)

From Act

I:

Duet (in E

flat, orig. in G), Susanna -

Figaro: "Cinque, dieci"

Duet (in E

flat, orig. in B flat).

Susanna - Figaro: "Se a caso

madama"

Cavatina (in

A flat, orig. in F).

Figaro: "Se

vuol ballare signor Contino"

Aria (in E

flat, orig. in C). Figaro:

"Non più andrai"

From Act

II:

Terzetto (in

E flat, orig. in C). Susanna

- Countess - Count: "Susanna

or via sortite"

Sedlak, too,

left out a large section of Il

barbiere di Siviglia

from his transcription, which

goes no further than the

middle of Act I, Scene 2.

Fortunately he chose the most

enduring of the pieces, many

of which occur in the first

act. One might only have

wished for Sedlak to have

finished the brilliant finale of

Act I. No score has been found

to his work. The parts are

numbered as follows:

1

Overture

From Act

I, Scene 1:

2-3

Introduction. Fiorello -

Count - Chorus: "Piano,

pianissimo" and Vivace

(Continuation of

Introduction after the

Count's aria). Count: "Ehi,

Fiorello!"

4-5 Aria,

Count: "Ecco ridente in

cielo" and "Oh sorte!"

6 Cavatina.

Figaro: "Largo al factotum"

7-8 Duet.

Figaro - Count: "All'idea di

quel metallo" and "Numero

quindici"

From Act

I, Scene 2:

9-10

Cavatina. Rosina: "Una voce

poco fa" and "Io sono

docile"

11 Aria.

Basilio: "La calunnia"

12 Duet.

Rosina - Figaro: "Dunque io

son"

One might be

tempted to speculate that any

music not transcribed but

actually written for a wind

group by the composer himself

must be an ideal work to

represent the genre. Certainly

Mozart's great Serenade in B

flat K. 361 (370a) for 13

winds supports this

hypothesis. Krommer's 13 Harmonien

were also excellent

representations of the style.

Mendelssohn wrote an appealing

Ouvertüre für Harmoniemusik,

Op. 24. Rossini's Harmonie

in F, heard here, may not have

been designed to ensure his

immortality, but it is still a

channing work. lt is an

example of Harmoniemusík

derived not from operatic or

military music, but from the

song, sonata, and dance forms

on which the pure instrumental

music of the 18th and 19th

centuries was based.

©

1993 David Montgomery

|

|

|