|

|

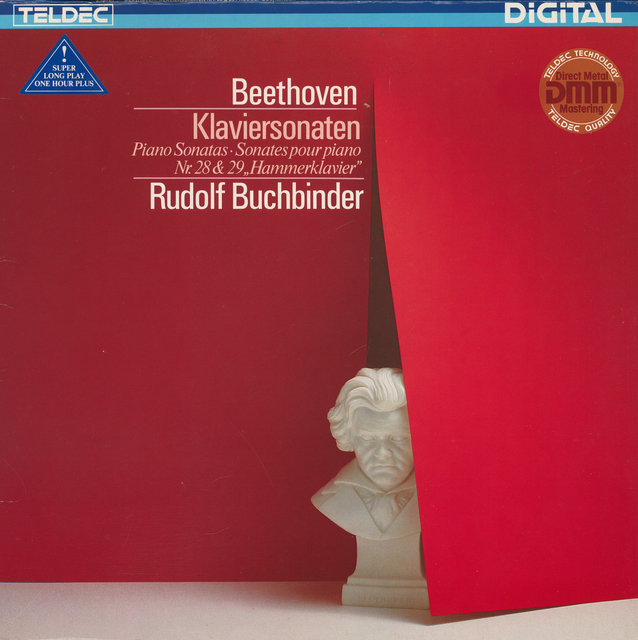

1 LP -

6.42761 AZ- (c) 1984

|

|

| 1 CD -

8.42761 ZK - (c) 1984 |

|

DIE

KLAVIERSONATEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van

BEETHOVEN (1750-1827) |

Klaviersonate

Nr. 28 A-dur, Op. 101 - Der

Freiin Dorothea von Ertmann

gewidmet (Komponiert um 1816)

|

|

20' 01" |

|

|

-

Etwas lebhaft und mit der innigsten

Empfindung: Allegretto ma non troppo

|

4' 05" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Lebhaft · Marschmäßig: Vivace alla

Marcia

|

5' 50" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Lansam und sehnsuchtsvoll: adagio,

ma non troppo, con affetto

|

2' 58" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Geschwinde, doch nicht zu sehr, und

mit Entschlossenheit: Allegro

|

7' 08" |

|

A4 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 29 B-dur,

Op. 106 "Große

Sonate für das

Hammerklavier" - Dem

Erzherzog Rudolph

von Österreich

gewidmet

(Komponiert 1817/18)

|

|

46' 04" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

10' 28" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Scherzo: Assai vivace

|

2' 16" |

|

A6 |

|

-

Adagio sostenuto: Appassionato e con

molto sentimento

|

20' 54" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Largo · Allegro · Allegro risoluto

(Fuga a tre voci, con alcune

licenze)

|

12' 26" |

|

B4 |

|

|

|

|

Rudolf BUCHBINDER,

Klavier (STEINWAY-Flügel)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

-

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

Telefunken

| 6.35596 FK - Vol.4 | 3 LPs | LC

0366 | durata: 55' 39" · 42' 47" ·

65' 59" | (p) 1982 | ANA | stereo

Teldec | 6.42761 AZ | 1 LP | LC

0366 | durata 66' 00" | (p) &

(c) 1984 | DDD/DMM | stereo

|

|

|

Edizione CD

|

|

Teldec |

8.42761 ZK | 1 CD | LC

3706 | (c) 1984

| DDD/DMM | stereo

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

-

|

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

-

|

|

|

Cover design

|

|

Holger

Matthies

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

| THE 32

PIANO SONATAS (10 CDs DMM) |

Piano

Sonata Nr. 28 A-dur, Op. 101

With this sonata, completed in

1816, Beethoven's creative work

began to flow again after several

years of sluggish production, not

unconnected with the political

confusion of the period. One of

the most striking innovations of

his late period style, which is

generally acknowledged as

beginning with op. 101, is an

emphatic move towards contrapuntal

writing, towards fugues,

particularly in his final movements

(piano sonatas opp. 101, 106, 110,

cello sonata op. 102, No. 2). In

op. 101 the finale, as in so many

others of his late works the

most weighty movement, completely

envelops the sonata form in

contrapuntal notions: in the

exposition all thematic

figurations are presented fugato,

the development and later, by

analogy, the coda begin with a

genuine four-part fugue on the

main subject in the tonic minor.

An adagio, highly expressive in

spite of being a mere twenty bars,

is headed ”langsam und

sehnsuchtsvoll”, i.e. ”slow and

yearning”; (in op. 101 Beethoven

continued the practice started

with op. 90 of using German

headings, although he added

Italian markings.) It is somewhat

reminiscent of the ”Introduzione”

in the Waldstein sonata, which

also ushers in the tremendous final

movement. In between, before the

”attacca” of the Finale, there is

a brief quotation from the first

movement, a device intended to

emphasise the cyclical unity of

the whole concept, which is later

encountered on several occasions,

notably in the Ninth Symphony. The

first movement is lyrical and

sensitive throughout, really more

in the style of a central slow

movement; here the differentiation

of form and theme which is

inherent in the sonata movement

proper has all but disappeared. (The

particular rhythm of the movement,

tied quavers on the weak beat

resulting in syncopation, is later

frequently to be found in the

works of Schumann and Brahms.)

Beethoven described this sonata as

very difficult to perform; he

dedicated it to one of the most

accomplished pianists in Vienna,

the Baroness Ertmann (“Receive

what I have often intended for you

and which, I hope, will prove my

devotion both to you and to your

artistic talent.”) Both Reichardt

and Mendelssohn considered her

interpretation of his works to be

perfection itself, and Anton

Schindler, Beethoven’s confident

and subsequently his biographer,

praised her in the following

terms: “Her achievements were

simply unique. She sensed

intuitively even the most arcane

intentions in Beethoven’s works

with such certainty as though they

were written out and in front of

her very eyes.”

Piano Sonata Nr. 29 B-dur, Op.

106 "Große Sonate für das

Hammerklavier"

This sonata, written in 1818, is

practically the only major work of

that year and the longest and most

difficult of all Beethoven's piano

sonatas; it almost strikes one as

a gateway leading to the

tremendous edifice of the ”Missa

Solemnis”, which he started

immediately afterwards. (The

epithet "Hammerklavier” Sonata,

derived from the original title

“Grand Sonata for the

Hammerklavier” has no significance

other than that in place of the

customary term ”pianoforte” he

used the equivalent German name,

as he did for example in op. 101.)

The publication of the sonata in

1819 was greeted with comments

such as these: ”Thus we can

observe, after only a few lines,

that this work does not just

differ from the master's other

creations in its abundant and vast

imagination but that, by virtue of

the artistic perfection of its

unified writing” (this refers to

the counterpoint of the fugue in

the last movement) “it appears to

mark a new period in Beethoven's

piano works.” This is his last

sonata in the grand, four-movement

structure, though the largo which

introduces the finale almost

achieves the status of an

independent movement, thereby

creating a roughly symmetrical

structure of five movements. The

longest movement, the adagio, lies

at the core, with two shorter

movements (scherzo and largo)

separating it from the huge outer

movements.

As in the

“Waldstein” and “Appassionata”,

the first movement is of truly

symphonic proportions, abounding

with changing harmonies, furious

contrasts, extraordinary tonal

effects, exploiting the extreme

registers of the piano and

demanding a degree of virtuosity

that is not merely an end in

itself. By contrast there follows

a fleeting yet somehow constrained

scherzo and a strange trio with

colourless broken triads leading

to a wild cadence, marked presto;

after the repeat of the scherzo

there is a coda with an oppressive

conflict between the last note,

the tonic B flat, and the “wrong”

B natural. The adagio, marked

“appassionato e con molto

sentimento”, with its very free

formal structure and its

tremendous dimensions (Beethoven’s

longest sonata movement along with

the “Arietta” of op. 111) is one

vast “espressivo” of movingly

intoned sounds of grief and

isolation with its climax in B

minor, the key which Beethoven in

1816 described on a sketch as the

“black key”. — The largo, a

completely free fantasia written

in part without bar lines, is

followed by the crowning edifice

of a “fuga con alcune licenze” (a

fugue with some degree of freedom)

taking up 400 bars, a worthy

counterpart to the “Grosse Fuge”

op. 133, originally planned as the

last movement of the string

quartet op. 130. Its counterpoint

is executed with every form of

sophistication, yet the overall

concept is one of tremendous

freedom; the part-writing is

complex, the rhythm and metre

extraordinarily difficult; one way

and another the whole

“Hammerklavier” sonata was

virtually beyond the capacity of

performers of the time. To his

publisher Beethoven wrote:

“There’s a sonata for you that

will give pianists trouble, and

will only be played in fifty

years’ time.” In the event it did

not take quite as long as that: it

was probably Franz Liszt who first

managed to play the

“Hammerklavier” sonata at a public

concert in Paris in 1836. Hector

Berlioz was full of enthusiasm:

“The ideal performance of a work

reputed to be unperformable; by

rendering a work which had until

then not been understood, Liszt

has proved that he is the pianist

of the future.” |

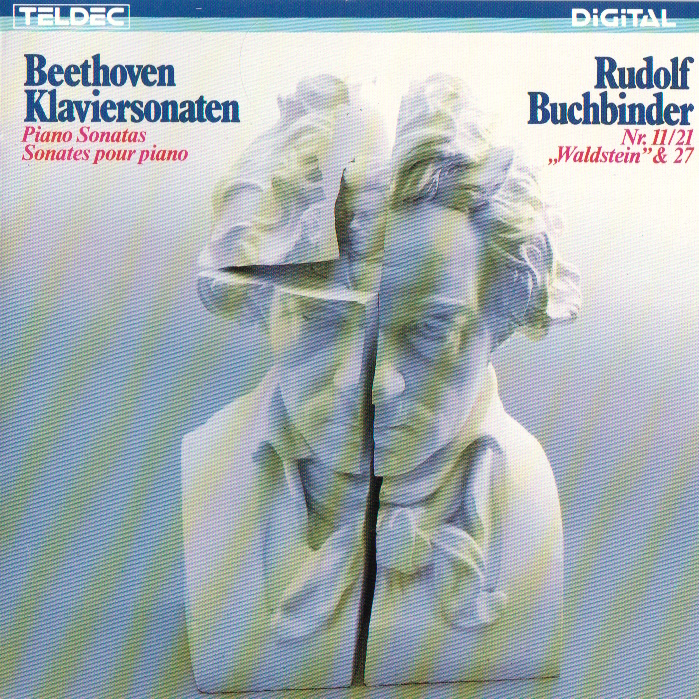

1 CD - 8.42761 ZK - (c) 1984

1 CD -

8.43027 ZK - (c) 1984

1 CD -

8.43027 ZK - (c) 1984

1 CD -

8.43206 ZK -

(p) 1985

1 CD - 8.43415

ZK - (p) 1986

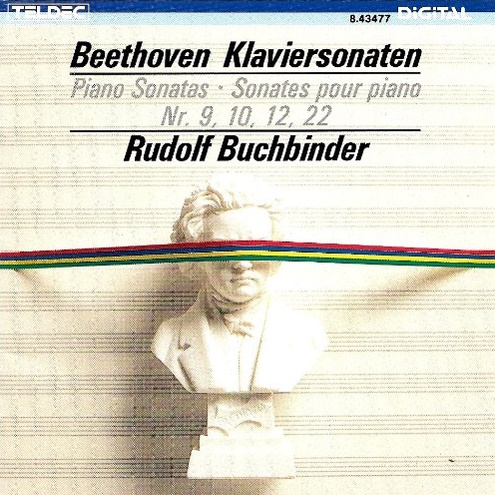

1 CD - 8.43477

ZK - (p) 1987

|

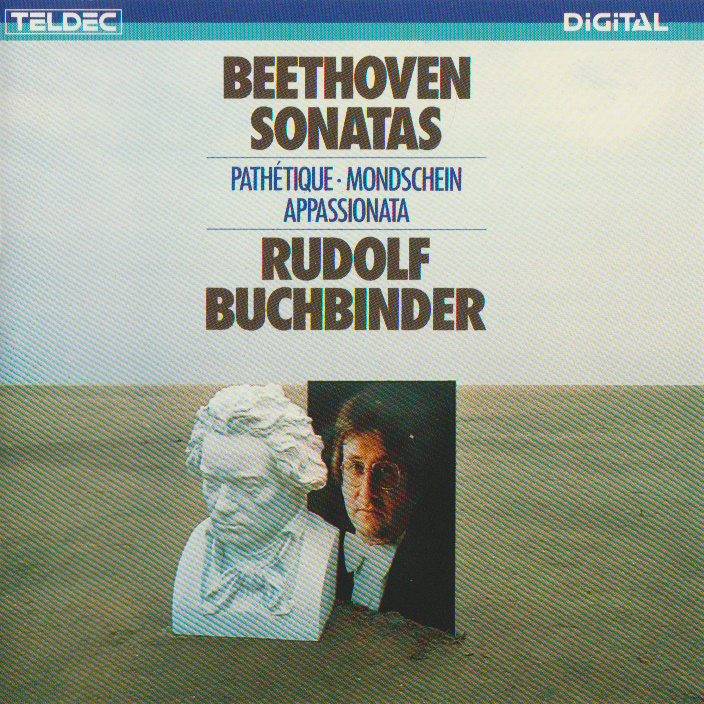

1 CD - 8.42913 ZK - (c) 1983

1 CD - 8.43111 ZK - (p)

1985

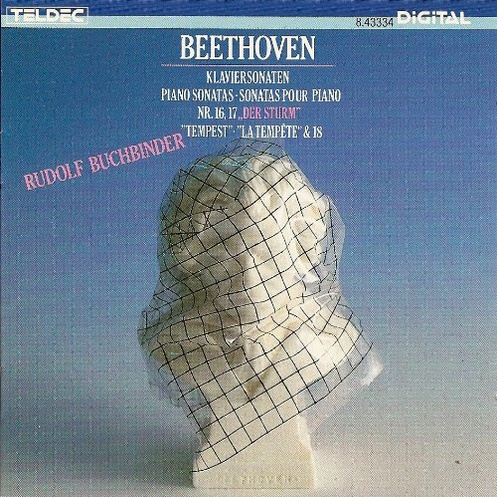

1 CD - 8.43334 ZK

- (p) 1986

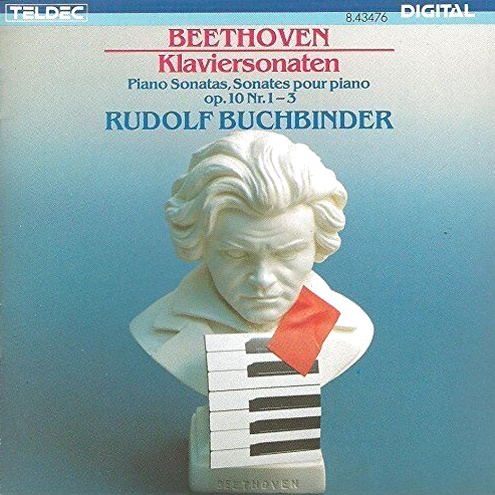

1 CD - 8.43476

ZK - (p) 1987

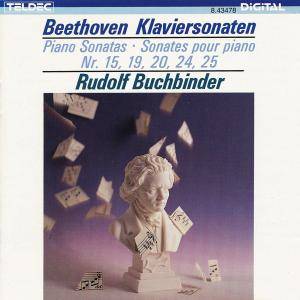

1 CD - 8.43478

ZK - (p) 1987

|

|

|

|

|