|

|

3 LPs

- 6.35450 EX - (p) 1978

|

|

| 2 CDs -

0630 17368-2 - (p) 1997 |

|

| 2 CDs -

2564 69223-7 - (p) 2009 |

|

| SÄMTLICHE

WERKE FÜR VIOLONCELLO UND KLAVIER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van BEETHOVEN

(1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sonate

Nr. 1 F-dur für Klavier und

Violoncello, Op. 5 Nr. 1 - dem

König Friedrich Wilhelm II. von

Preußen gewidmet

|

|

20' 57" |

A

|

-

Adagio sostenuto · Allegro

|

14' 12" |

|

|

| -

Rondo. Allegro vivace |

6' 35" |

|

|

| Sonate

Nr. 2 g-moll für Klavier

und Violoncello, Op. 5 Nr.

2 - dem König Friedrich

Wilhelm II. von Preußen

gewidmet

|

|

24' 57" |

B |

-

Adagio sostenuto ed espressivo ·

Allegro molto più tosto presto

|

23' 50" |

|

|

| -

Rondo. Allegro |

9' 07" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sonate

Nr. 3 A-dur

für Klavier

und

Violoncello,

Op. 69 - dem

Freiherrn Ignaz

von Geischenstein

gewidmet

|

|

23' 53" |

C |

| -

Allegro ma non tanto |

9' 32" |

|

|

-

Scherzo. Allegro molto

|

5' 39" |

|

|

-

Adagio cantabile · Allegro vivace

|

8' 42" |

|

|

| Sonate

Nr. 4 C-dur

für Klavier

und

Violoncello, Op. 102 Nr. 1 - der Gräfin

Marie von

Erdödy

gewidmet

|

|

15' 19" |

D1

|

| -

Andante · Allegro vivace |

8' 08" |

|

|

| -

Adagio · Allegro vivace |

7' 11" |

|

|

| 7

Variationen

Es-dur über

das Thema "Bei

Männern,

welche Liebe

fühlen", aus Mozarts "Die Zauberflöte"

für Klavier

und

Violoncello,

WoO 46 - der Grafen Johann Georg von

Browne

gewidmet |

|

10' 18" |

D2 |

-

Tema. andante

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sonate

Nr. 5 D-dur

für Klavier

und

Violoncello, Op. 102 Nr. 2 - der Gräfin

Marie von

Erdödy

gewidmet

|

|

20' 32" |

E |

| -

Allegro con brio |

6' 50" |

|

|

| -

Adagio con molto sentimento

d'affetto |

9' 46" |

|

|

| -

Allegro · Allegro fugato |

3' 56" |

|

|

12

Variationen F-dur +ber "Ein

Mädchen oder Weibchen", aus

Mozarts "Die Zauberflöte" für

Klavier und Violoncello, Op. 66

|

|

9' 32" |

F1 |

-

Tema. Allegretto

|

|

|

|

12

Variationen G-dur über ein Thema

aus Händels Oratorium "Judas

Maccabäus" für Klavier und

Violoncello, WoO 45 - der

Fürstin Christiane von Lichnowsky

gewidmet

|

|

12' 48" |

F2 |

| -

Tema. Allegretto |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rudolf BUCHBINDER,

Klavier (Bösendorfer-Flügel)

Janos STARKER, Violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Teldec

Studio, Berlin (Germania) - 25/26

aprile 1978

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

Telefunken

| 6.35450 EX | 3 LPs | LC 0366 |

durata: 45' 54" · 49' 30" · 42'

52" | (p) 1978 | ANA | stereo

|

|

|

Edizioni CD

|

|

Teldec

| 0630-17368-2 | 2 CDs | LC 6019 |

durata 68' 27" ·

69' 31" | (c) 1997 |

ADD | stereo | Remastered

Warner

Classics "Apex" | 2564 69223-7 |

2 CDs | LC 04281 | durata 68' 31

·

69' 33"

| (c) 2009 | ADD |

stereo | Remastered |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Heinrich

J. Weritz

|

|

|

Recording

Producer and Tonmeister |

|

?

|

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

?

|

|

|

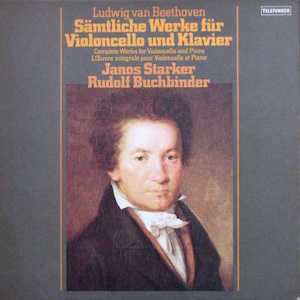

Cover |

|

Ludwig

van Beethoven, Gemälde von J. W.

Mähler, 1815

|

|

|

Art Direction

|

|

?

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

BUCHBINDER

& BEETHOVEN

6 LPs - 6.5289 FK - (p) 1976

6 LPs - 6.35368 FK

- (p) 1977

6 LPs - 6.35368 FK

- (p) 1977

3 LPs -

6.35450 EX - (p) 1978

|

Complete

works for cello and piano

The laws of art are often

unfathomable; not infrequently its

further paths, its fate, appear to

he even more unfathontable. This

once again becomes evident From

the Beethovcn cello works which

even still today - particularly as

an integrated unit - tend to be

regarded as a part of the unknown

Beethoven. The especial element of

Beethoven's autograph works

deserved interest in certain part

sectors. and this is most

definitely the case with the works

introduced here; for in their own

way they provide an indication of

Beethoven's general compositional

development. A new aspect is

treatment of the instrumental duet

as such, but a further new element

is Beethoven's method towards

simultaneous creative work in

other fields. The two last sunatas

op. 102 are unparalleled works

which, composed at such an early

period, point to a style in the

far distant future.

"Deux Grandes Sonates pour le

Clavecin ou Pianoforte avec un

Violoncelle obligée" is the title

of the two sonatas op. 5. In this

connection the noteworthy point is

not only that the cello - contrary

to present-day understanding -

does not appear as accompanying

instrument to the piano, but that

there is express reference to

obbligato application. This is a

rejection of the old baroque

practice of a solo instrument with

basso continuo accompaniment, with

corresponding liberties of the

accompanist as his own

contribution. That this reference

in the present edition was not a

mere coincidence is apparent from

Beethoven's more express

instructions in a different

context. Just a few years later he

wrote to the Leipzig publisher

Hoffmeistet concerning the parts

of his septer op. 20: "Tutti

obligati. (I cannot write anything

non-nbbligato because l already

came into the world with an

obbligato accompaniment". Thus

Beethoven was less concerned with

creating a fundamentally fresh

style for the cello sonata, than

coining a new form of the solo

sonata with two firmly

interrelated instrumental parts;

over and above this, the cello

departed from its heterogeneous

function of mere reinforcement of

the bass and was given a

self-sufficient and independent

significance. As regards

individual works, it is always

advisable to enquire as to the

particular occasion. Beethoven had

written the op. 5 sonatas in 1796

during a visit to Berlin for

Pierre Duport, the first cellist

of the Prussian Court Orchestra.

and performed it together with him

at the court. In his way he

probably took to heart what

Christian Friedrich Daniel

Schubart had once said about

Duport: "He plays the violoncello

with such magic power that it is

difficult to find anybody in Europe

to equal him. He guides the bow as

in a storm and rains down notes.

He rises above and beyond the

extreme heights of the fingerboard

and finally disappears in the

rnost delicate harmonics“.

Incidentally King Friedrich

Wilhelm II of Prussia, to whom the

sonata was dedicated, was also an

expert in this field; he enjoyed

Duport's tuition and was regarded

as a diligent cellist and keen

chamber music player.

As is the case with most of the

piano works. the cello works are

also orientated to the forms of

the sonata and of the theme with

variations. The sonatas op. 5 bear

their own stamp in so far as each

consists of two movements and

waives the usual slow middle

movement as well as the scherzo;

both have an adagto introduction

as the opening movement, and a

rondo as the concluding movement.

In his endeavour to bring the

cello more strongly into the

foreground, Beethoven by no means

neglected the piano part, as one

can already see at the beginning

of the 1' sonata. At the end of

the brief adagio introduction it

makes a brilliant impression with

a wide-ranging cadenza-like

passage. But even the allegro

beginning which immediately

follows on indicates that the

piano is allotted the task,

appropriately accorded to the

orchestra in instrumental

concrtos, of guiding the themes of

the solo. Furthermore there are

themes which appear to be inspired

purely and simply by the cello -

passages and cantilenas at any

rate which in all positions are

able to emphasise the unmistakable

singularity of the instrument.

Beethoven had always been a master

of the art of contrasts and

especially so when it was a matter

of such markedly individual

characters such as the piano and

cello. This contrast-related

design is rnost effective in the

mobile forward-pressing first

theme compared to the retarding

syncopated beats of the second

theme. The conspicuous thematic

diversity, which incidentally the

two sonatas have in common,

results in Beethoven to a large

extent abandoning his usual

technique of motif and thematic

development in favour of freer and

more imaginative progress.

In many respects the second sonata

already seems to be somewhat

further developed; although

featuring several common aspects

in the overall attitude, it

nevertheless displays a noticeable

increase in expression. From the

outset, the beginning recalls the

mood of the pathos-laden piano

sonatas which are so typical of

Beethoven; we hear mighty chords

and dotted rhythms which are

further developed throughout the

entire introduction. The lively

dialogue between the two

instruments at the beginning of

the allegro makes a most charming

impression, especially in

preparation of the spirited focal

point which is accompanied by

piano triplets. The most genuine

Beethoven is quite clearly heard

in the concluding rondo, a

delightful sample of his

much-lauded humour, as if created

specifically for the virtuoso arts

of an executant of Duport’s

calibre. It reminds the listener

of Beethoven’s frequently

expressed preference for swelling

finales.

No detailed information has been

passed on concerning the

Beethoven-Duport performance. With

the Sonata in A major op. 69,

composed more than ten years

later, Beethoven most probably

wanted to compensate his friend

Ignaz von Gleichenstein, for whom

the Piano Concerto in G major op.

58 was originally intended but to

whom it was not, in fact,

subsequently dedicated.

Gleichenstein was by profession a

planner at the royal and imperial

court war council, as was also

Beethoven's friend Stephan von

Breuning. Beethoven appreciated

Gleichenstein for his education,

his kind-heartedness and also on

account of his excellent cello

playing. The diverse pastimes of

the two friends went as far as a

joint search for a bride.

Gleichenstein was tactful enough

not to want to be immortalised

with his official title in the

first edition of the work; this

can be seen from the

correspondence between Beethoven

and his publisher. Dedication of

the work to Gleichenstein may have

prompted Beethoven to reduce the

virtuoso demands somewhat -

something which he was able to

make up for in other sectors.

Right from the beginning the cello

alone is heard playing a splendid

melody, an absolutely first-class

example of the instruments

beautiful sonorous depths. The

fact that the thematic sequence of

this sonata to a large degree

renounces contradictory elements

should not be prematurely

construed as a weakness in the

work. At least in a clear

indication of self-reliance in the

cello part we observe a sign of

increasing maturity. The only

astounding aspect is how the Fifth

Symphony, a completely different

type of work, with its extremely

compulsive germinating motif

developments, could have been

composed in the same creative

phase as this cello sonata, as is

evident from an examination of the

sketches. Worthy of particular

note is the scherzo, which already

has an unusually high standing

because of its external

dimensions: 519 bars compared with

280 bars in the opening movement

and 220 in the finale. In this

case too an adagio is limited to a

brief introduction into the finale,

a period of quiet before the storm

which appears to have more of an

interim function than a

significance of its own.

Beethoven’s correspondence with

his publisher concerning this

sonata proves, inter alia, the

importance of the dynamic marks in

which even Beethoven himself did

not always seem to be infallible.

In a letter dated 3 August, 1809

for instance he writes: "Do not

laugh about my author-like

apprehension. Just imagine, I find

that in correcting the mistakes in

the violoncello sonata I have made

new errors. Therefore: in the

scherzo allegro molto this ff

remains as it was indicated in the

first places". - And indeed the

scherzo does not live too frugally

from the dynamic refinements.

Personal relationships are also

associated with the two sonatas in

C major and D major op. 102. They

were dedicated to Countess Marie

Erdödy and evidently intended for

her and the cellist Joseph Linke

who was closely connected with her

music-loving home. Beethoven’s

cordial relations with this

countess are reflected in numerous

letters which have been preserved.

But precisely at this point the

question has to be asked as to how

much the dedication of these works

has to do with her singular

figure. Even contemporaries did

not refrain from expressing fitting

criticism. The "Allgcmeine

Musikalische Zeitung" of 11

November, 1818 wrote: "These two

sonatas are quite definitely among

the most unusual and peculiar

written for the pianofotte for a

long time, not only in this form

but generally. Everything here is

different, quite different. from

what we have otherwise received,

even from this master himself. We

trust he will not take it amiss if

we add that not a little as it is

written here now, and as it is

arranged, published and

distributed, also appears to be

designed in such a way that it

will emerge in a quite unusual,

quite strange fashion". What was

attracting adverse criticism here

in its initial stages was nothing

else but Beethoven's late style.

now appearing ro an increasing

extent, about the unfavourable

reception of which he himself had

no illusions; for a little while

later he countered complaints

about the disagreeable, difficult

style of his piano sonata op. 101

with his own philosophy that

"difficult" was a relative term,

but that for the rest the maxim

applied: "what is difficult is

also beautiful, good, great etc.

Every man will therefore see that

this is the biggest praise that

one can give, since what is

difficult makes one eweat".

The departure from the

well-trodden paths is most

noticeable in the C major sonata

in as much as the usual cyclic

sequence is only hinted at in the

time changes with a corresponding

change in the musical course,

while basically the entire work

consists of a single

imagination-permeated movement. In

addition to this the motif and

thematic development remains

extremely free and unbound.

Beethoven, evidently quite

intentionally, replaces the

customary thematic compactness of

his thoughts by an often seemingly

stereotyped, short-winded

motif-thematic entity which the

two instruments play towards each

other at brief intcrvals,

occasionally even using stretto

style. This is effected with a

generally unmistakable tendency

towards that polyphonic manner of

composition which was to become so

typical of Beethoven’s late style.

Development is in many cases

shifted only to the rhythmic and

dynamic sectors. Similarly the so

characteristic trills of the late

piano sonatas and quartets are not

omitted in this strange game of

the, so to speak, disembodied and

spiritualised elements.

In many respects Beethoven takes a

somewhat more "conciliatory" line

in the second sonata. This appears

to be announced in the srnall.

compact melodic arc of the

introductory piano bars,

especially since this is continued

in a beautifully sweeping

cantilena on the cello. Once again

the whole is essentially a

richly-inspired fantasia, but this

time one with more marked concepts

and a longer range. A clear

pointer to the future are the

harmonic liberties in the

development which never before had

been experienced to this extent in

Beethoven's works. In the course

of greater compactness of the

individual sonata movements, a

slow movement is now also able to

achieve greater development. It is

one of those strongly expressive

adagios which were already to be

found in Beethoven's early piano

sonatas. Eight bars of solemn,

choir-like striding and

luxuriating in beautifully full

tones precede the momentous theme

declaiming "con molto sentimento

d'affetto", which appears

eminently to bring out the

expressive range of the

violoncello. A rhapsodic, free

further development of this

concept is joined by a simple,

initially song-like and then

variation-type part, in which the

illuminating major key has a

liberating and relaxing effect.

What then follows is a restrained

conclusion related to the

beginning.

By way of some timid, brief movcs

which recall the beginning of the

finale of the First Symphony, the

adagio proceeds directly into the

concluding movement, a

construction which probably is the

clearest anticipation of

Beethoven's late style. This is

one of Beethoven's so typical

mixtures of an initially strict

fugue - in this case in four parts

- with highly diverse motif

modification of individual

component parts. One enters a

world of abstract, constructivist

polyphony, with lively reminders

of Bach, in which the spirit of

the grand fugue clearly flares up

from the region of the last

quartet. Beethoven's apparent

struggle for new stylistic

possibilities is not the only

reason why these two sonatas are

accorded a key position in his

creative output. It also has to be

borne in mind that these are the

only two larger instrumental works

which Beethoven composed in this

particular year, 1815. A symphony

and a piano concerto did not get

beyond the planning stage at that

time.

In the normal course of events

Beethoven did not accord a great

deal of significance to his

variation works; as far as the

effort put into them was concerned

they sometimes hardly differed

from his extempore improvisations.

The outsider might evaluate them

differently. At any rate, most of

the variation works were

consciously not alloted opus

numbers. The reasons are obscure

as to how the variations on "Ein

Mädchen oder Weibchen" from

Mozart's "Magic Flutes" came to be

listed as opus 66. For all this,

the work does not take its place

between op. 65 and op. 67.

The twelve variations on a theme

from Handel's "Judas Maccabaeus"

were presumably composed in 1796,

the year in which the two sonatas

op. 5 were written. This was an

carly act of homage to the master

whom Beethoven greatly revered

throughout his life. This is also

reflected musically in occasional

conspicuous traits of the organ

toccata and the cottcerto gtosso,

as well as a tendency towards

polyphonic compositional style.

Beethoven most likelz became

acouainted with Handel's works in

the home of the art loving Baron

van Swieten in the early Vienna

years. A point worth mentioning

here is the independent role also

accorded in this case to the

cello.

Mozart's "Magic Flute" was one of

Viennaßs really big operatic

attractions at that time and thus

it is hardly surprising that

Beethoven on two occasions

composed variation-type

developments on themes from the

work. The twelve variations in F

major on "Ein Mädchen oder

Weibchen" were written in

connection with the original

edition, which appeared in

September, 1798, or probably just

before this. A notable point here

is that this time Beethoven

slightly altered the theme in as

much as he lets the second part -

which in Mozart's version is

written in 6/8 time - carry on in

the 2/4 time of the beginning.

Incidentally, this is the first

Beethoven work reviewed in the

famous "Allgemeine Musikalische

Zeitungt", albeit hardly to the

composerßs delight. What the

journal took amiss, however, was

not for instance Beethovenßs

arbitrary alteration of the theme,

but his all too bold modulations,

transitions and hardness,

particularly in Variation XII,

where he modulates from F major to

D major, then falling back again

to F major. Beethoven's merit as

regards the independent leading of

the cello was not one of the

questions which was dear to the

heart of the reviewer at that

time.

The seven variations on "Bei

Männern, welche Liebe fühlen"

prohahly owe their existence to

two extremely successful repeat

performances of the Magic Flute in

1801. With regard to these

variations. the reviewer thought

that they were not among the

excellent works usually expected

of Beethoven, but nevertheless

conceded: "Anybody wanting to

perform these cello parts must he

a consummate master of his

instrument".

As an example of Beethoverßs

variation compositions at that

time, these variations are of

intrinsic value in as much as they

were composed close to the time in

which the two famous piano

variations op. 34 and op. 35 were

written, which Beethoven himself

emphasised as being at the

crossroads of a completely new

trend marking the turn towards the

middle style period. In actual

fact, in several passages of the

afore-mentioned Magic Flute

variations one is reminded of op.

34.

by

Hans Schmidt

(English translation by

Frederik A. Bishop)

|

|

|

|