|

|

3 LPs

- 6.35490 FK - (p) 1981

|

|

| 8 LCDs -

9031-71719-2 - (c) 1990 |

|

KLAVIERSONATEN

- Volume 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van

BEETHOVEN (1750-1827) |

Klaviersonate

Nr. 1 f-moll, Op. 2 Nr. 1 - Joseph

Haydn gewidmet (Komponiert um

1795)

|

|

16' 24" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

3' 22" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Adagio |

5' 27" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Menuetto: Allegretto |

2' 55" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Prestissimo

|

4' 40" |

|

A4 |

|

Klaviersonate

(Leichte Sonate) Nr. 19 g-moll,

Op. 49 Nr. 1 (Komponiert 1795/98)

|

|

7' 07" |

|

|

-

Andante

|

3' 54" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Rondo: Allegro

|

3' 13" |

|

A6 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 2 A-dur, Op. 2 Nr. 2 - Joseph

Haydn gewidmet (Komponiert

1795)

|

|

21' 32" |

|

|

-

Allegro vivace

|

6' 26" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Largo appassionato

|

5' 54" |

|

B2 |

|

-

Scherzo: Allegretto

|

3' 11" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Rondo: Grazioso

|

6' 01" |

|

B4 |

|

Klaviersonate

(Leichte Sonate) Nr. 20 G-dur,

Op. 49 Nr. 2 (Komponiert 1795/98) |

|

8' 21" |

|

|

-

Allegro, ma non troppo |

4' 38" |

|

B5 |

|

-

Tempo di Menuetto

|

3' 43" |

|

B6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 12 As-dur,

Op. 26 - Dem

Fürstin Carl von

Lichnowsky

gewidmet

(Komponiert

1800/01)

|

|

19' 01" |

|

|

-

Andante con Variazioni

|

7' 24" |

|

C1 |

|

-

Scherzo: Allegro molto |

2' 29" |

|

C2 |

|

-

Marcia funebre sulla morte d'un Eroe

|

6' 38" |

|

C3 |

|

-

Allegro |

2' 30" |

|

C4 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 15 D-dur,

Op. 28 "Pastorale" -

Joseph Edlen von

Sonnenfels

gewidmet

(Komponiert 1801)

|

|

22' 13" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

9' 14" |

|

D1 |

|

-

Andante |

6' 21" |

|

D2 |

|

-

Scherzo: Allegro vivace

|

1' 53" |

|

D3 |

|

-

Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo |

4' 45" |

|

D4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 21 C-dur, Op. 53 "Waldstein-Sonate" - Dem

Grafen

Ferdinand von

Waldstein

gewidmet

(Komponiert

1803/04)

|

|

21' 46" |

|

|

-

Allegro con brio

|

9' 12" |

|

E1 |

|

-

Introduzione: Adagio molto

|

3' 37" |

|

E2 |

|

-

Rondo: Allegretto moderato

|

8' 57" |

|

E3 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 32 c-moll, Op. 111 - Dem

Erzherzog Rudolph von Österreich

gewidmet (Komponiert 1821/22)

|

|

27' 07" |

|

|

-

Maestoso · Allegro con brio ed

appassionato

|

8' 56" |

|

F1 |

|

-

Arietta: Adagio molto semplice e

cantabile

|

18' 11" |

|

F2 |

|

|

|

|

Rudolf BUCHBINDER,

Klavier (Steinway-Flügel)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

-

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

Telefunken

| 6.35490 FK | 3 LPs | LC 0366 |

durata: 53' 24" · 41' 14" · 49'

53" | (p) 1981 | ANA | stereo

|

|

|

Edizione CD

|

|

Teldec

| 9031-71719-2 | 8 CDs | LC

3706 | (c)

1990 | DDD/DMM | stereo |

Klaviersonaten Nr. 1-32

Teldec | 8.43415 ZK | 1 CD | LC

3706 | (c)

1986 | DDD/DMM | stereo |

Klaviersonaten Nr. 1, 2

Teldec

| 8.43478 ZK | 1 CD | LC 3706 |

(c)

1987 | DDD/DMM | stereo |

Klaviersonate Nr. 19, 20, 15

Teldec |

8.43477 ZK | 1 CD | LC 3706

| (c)

1987 | DDD/DMM | stereo |

Klaviersonate Nr. 12

Teldec

| 8.43111 ZK | 1 CD

| LC 3706 | (c)

1985 | DDD/DMM |

stereo |

Klaviersonate Nr. 21

Teldec

| 8.43027 ZK |

1 CD | LC 3706

| (c)

1984 | DDD/DMM

| stereo |

Klaviersonate

Nr. 32

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

-

|

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

-

|

|

|

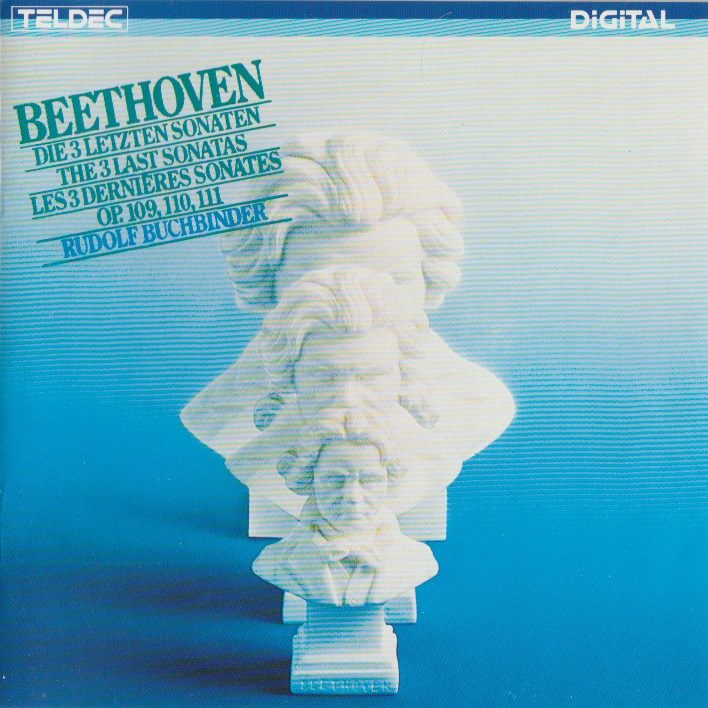

Cover |

|

Ludwig

van Beethoven, Gemälde von J. W.

Mähler, 1815

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

BUCHBINDER

BEETHOVEN

32 KLAVIERSONATEN

3 LPs - 6.35472 FK - (p) 1980

3

LPs - 6.35490 FK - (p) 1981

3 LPs -

6.35581 FK - (p) 1982

3 LPs -

6.35596 FK - (p) 1982 |

RE-RELEASE

ON

COMPACT DISC (DMM)

1 CD - 8.43415 ZK - (c) 1986

(Nr.1,2)

1 CD - 8.43478 ZK

- (c) 1987 (Nr.19,20,15)

1 CD - 8.43478 ZK

- (c) 1987 (Nr.19,20,15)

1 CD -

8.43477 ZK - (c) 1987

(Nr.12)

1 CD -

8.43111 ZK - (c) 1985

(Nr.21)

1 CD -

8.43027 ZK - (c) 1984

(Nr.32)

|

Piano

Sonatas Nr. 1 f-moll, Op. 2

Nr. 1 - Nr. 2 A-dur, Op. 2 Nr.

2

The first compositions that

Beethoven published in Vienna,

where he had moved from Bonn in

1792, were the three Piano Trios

op. l. These were soon followed

by the three Piano Sonatas op. 2

dedicated to his teacher Joseph

Haydn. (Actually the lessons

were very sporadic and the

rapport between the pupil and

his older “master,” then at the

height of his fame throughout

Europe, was evidently none too

easy.) The sonatas were written

in 1795, based on earlier

material, and printed in the

following year. Not only are

they entirely different from one

another, but they constitute in

themselves an ascending

sequence. While No. 3 is a

completely free, highly

individual work, No. 1 is still

comparatively conventional, and

no doubt intentionally so.

The first movement is extremely

terse, the exposition occupying

a mere 48 bars. Compactness is

the order of the day, there is

no unnecessary loquacity there

are no flourishes. This

concentration, which is also

particularly apparent in the

third movement, is in itself a

homage to Haydn. Beethoven opens

the first of his sonatas to be

accepted in the canon with a

commonplace: the ascending

broken minor triad at the

beginning of the piece, known in

the profession as the “Mannheim

rocket,” was in general use at

the time; one is constantly

reminded of the similarity to

the opening of the last movement

of Mozart’s G minor Symphony, K.

550. But what Beethoven does

with this motif is by no means

commonplace; the very first

sequence omits the anacrusis,

and thereafter only the turn

which concludes the opening

phrase is elaboratetd. Thus

Beethoven proves within a mere

eight bars what he can do with

this very ordinary tag, and that

what matters is not the basic

idea, but its musical

exploitation. "Development" is

not confined to the development

section of the sonata form, but

is to be found everywhere, in

every little detail. Beethoven’s

principle of continuous thematic

work, of composition as a

process - a notion which stems

primarily from Haydn - is

revealed even in this tiny

aspect of his first piano sonata.

In contrast to the concisely

stern, rather sombre sonata in F

minor, the finale of which

Czerny described as being

stormy, almost dramatic, like

the description of some serious

event, in the second sonata of

op. 2, in Beethoven's usually

bright and optimistic key of A,

a wayward, charmingly playful

note predominantes. The theme of

the last movement is quite

delightful: a graceful leap

across 3-1/2 octaves up to E in

Alt, the highest note in the

whole movement, which occurs

within the context of this

theme, and down again in an

almost exaggerated slide. One

might almost believe that

Beethoven chose the rondo form

in order to re-use this little

treasure: it occurs 5 times in

all, and the peak is attained in

a different manner on every

occasion. The beginning of the

scherzo almost anticipates the

Rondo opening: here again there

is a scurrying figure, the

broken A major triad ending,

surely not by chance, on exactly

the same note, E in Alt.

The first movement is on a very

large scale indeed, in

comparison with that of op. 2,

No. 1, which is not even half as

long; contrast, surprises and

internal relationship abound

and, unlike the uncomplicated

first sonata of the set, it is

as taxing as it is appealing to

the virtuoso. Both subject are

wayward and unexpected: the

first which, like the opening of

some Haydn symphonies, is full

of contrast, begins with two

terse, country motifs played

piano (but note the different

dynamics in the recapitulation).

The second subjet is introduced

not in the customary dominant

major, but in the gentle minor,

unceasing, unexpected

modulations, always introduced

by a dissonant note emphasised

by a sforzato, transform it into

a variant of the first subject

with abrupt dynamic contrasts.

The strongest possible

antithesis is provided by the

largo appassionato with its

almost orchestral writing and

fascinating display of different

reisters, which Czerny described

as bieng of a religious nature:

the sustained, broadly sweeping

tune is contrasted with the

generous palette of the

accompaniment, extending from

the dry staccato of the bassoon

to the cantilena of the strings.

Piano Sonatas Nr. 19

g-moll, Op. 49 Nr. 1 - Nr.

20 G-Dur, Op. 49 Nr. 2

These two pieces were

published in 1805 in Vienna

under the title ”Deux sonates

faciles pour le pianoforte.”

Beethoven's brother Carl had

already offered them without

success to German publishers

some years previously,

possibly even without the

composer's knowledge. They

were probably written in 1795

(No. 2) and 1796/98 (No. 1},

and are in essence sonatinas,

possibly occasional works

written for teaching purposes;

with the two Rondos of op. 51,

the first of which also dates

from 1796, they are

Beethoven's technically least

demanding piano works. Indeed,

Czerny did not include them in

the canon of piano sonatas

(which he, quite properly from

his point of view, treated as

consisting of 29 valid works;

the subsequent establishment

of a canon of 32 sonatas being

simply attributable to the

opus numbers) and described

them all bluntly as being

suitable for not particularly

expert players. It seemed an

obvious move to publish the

two pieces of op. 49 together:

both are in two movements and

represent the major and minor

modes of the key of G. Joachim

Kaiser has drawn attention to

some obvious allusions to

Mozart in the Sonatina in G

minor, including one to the

wellknown "Sonata facile,” K.

545. Shortly afterwards - in

1799 - Beethoven used the

theme of the Menuet of Sonata

No. 2 for the Menuet of his

Septet op. 20.

Piano

Sonata Nr. 12 As-dur, Op. 26

This work and the two sonatas of

op. 27, both subtitled ”quasi

una Fantasia," were all written

in the period 1800/01 and have

in common departures from the

traditional sonata form. This

applies particularly to the first

movements: in the two sonatas of

op. 27 Beethoven used a free

ternary form, whereas op. 26

begins with a set of variations.

Superficially Mozart's great

Sonata in A, K. 331, the first

movement of which is also an

Andante con variazioni, provides

the model; but Beethoven's

conception of the principle of

variation, cast for the first

time in a new mould in op. 26,

stretches far beyond the

innocent and cheerful

embellishments of the past.

These are "character variations”

in that each piece has its own,

unmistakeable features. In this

opening movement of op. 26

Beethoven explored, as though

for the first time, the

possibilities inherent in the

variation form which, shortly

afterwards (in 1802), were

presented in the two sets of

variations op. 34 and op. 35

(the ”Eroica” Variations) "in an

entirely new manner,” as he

proudly wrote to his publishers.

The second substantial departure

from the sonata model in op. 26

is the replacement of the slow

movement by a ”marcia funebre,”

i.e. a funeral march, subtitled

”sulla morte d'un Eroe” ("on the

death of a hero”). While in the

”Eroica” (subtitled ”to

celebrate the memory of a great

man”) actual references to

Napoleon, the contemporary hero

of world history, and the

tradition of depicting battles

in music were interwoven in an

overall poetic impression, op.

26 cannot be described as a

“heroic” sonata. So far no clues

have been discovered as to

Beethoven's choice of a funeral

march, nor about its subtitle.

Nonetheless the movement soon

became famous; it was published

on its own in the same year as

the first edition of the sonata

proper - 1802 - and has

continued to appear in that

form; Beethoven himself

orchestrated it in 1815 as

incidental music for a play; and

after his death in 1827 Ignaz

Ritter von Seyfried published an

arrangement of the piece with

added vocal quartet, entitled

”Beethoven’s funeral.”

In complete contrast, this

severe, solemn march is followed

by a deliberately lighthearted

finale rippling along in

ceaseless semiquavers. This

sonata, like the ”Pathétique”

op. 13 and the Trios op. 1, is

dedicated to Prince Carl von

Lichnowsky, Beethoven's most

important patron, of whom he

said in 1805: "He really is -

exceptionally for one in that

position - one of my most

faithful friends and supporters

of my art.

Piano

Sonata Nr. 15 D-dur, Op. 28

“Pastorale”

The fourth piano sonata to

appear in 1802, after op. 26 and

the two sonatas of op. 27, was

op. 28, written in 1801. In

comparison with its three

predecessors it is doubtless a

more lightweight composition,

presenting problems neither of

form nor of interpretation.

Perhaps there is some slight

connection between the serenely

restrained character of the

music and that of the dedicatee,

the nobleman Joseph von

Sonnenfels, a scholar and

statesman already in his

seventies, a respected upholder

of Enlightenment, whom Beethoven

apparently wished to honour;

nothing is known of any personal

acquaintance. The sonata

acquired its nickname quite

early on in English editions,

even before the Pastoral

Symphony (1807/08): it probably

derives from the bagpipe-like

bass figure in 6/8 time which

imparts a characteristic flavour

to the last movement. (As late

as 1842 Czerny attributed the

nickname specifically to the

finale: “A cheerful pastorale,

jocose and good-natured.”) One

should not, however, allow these

associations to obscure the fact

that the work displays

significant structural

relationships. The two outer

movements are linked by an

insistant drone-like D in the

bass, lasting almost 40 bars in

the first movement, and by the

virtually identical beginning of

the first subjects of both

movements. The link between the

first and third movement is

provided by a striking rhythmic

motif - both movements are in

3/4 time: two crotchets plus a

crotchet rest in the epilogue of

the first movement and the main

theme of the Scherzo, and its

inversion in the middle section

of the first movement and the

Trio of the Scherzo. The three

main thematic groupings of the

first movement are distinguished

by the clear difierences in their

rhythmic character; this is

paralleled to a certain extent

by the pronounced contrast

between legato and staccato in

the various sections of the

second movement. According to

Czerny, this movement, an

andante, was for many years one

of Beethoven's favourite pieces;

he often played it just for

himself.

Piano

Sonatas Nr. 21 C-dur, Op.

53 "Waldstein-Sonate"

This sonata,

which dates from 1803/04, is

one of a number of major works

written at that time: the

“Eroica” Symphony, the Triple

Concerto and, first and

foremost, the opera “Fidelio”,

then still called “Leonore”.

With the “Appassionata” op.

57, composed in 1804/05, the

“Waldstein” signifies a new

phase in Beethoven’s sonata

writing. This is the first

appearance of the “great”

sonata, great not only in its

dimensions but also in its

structure which, while scaling

almost symphonic heights,

shows in the arrangement of

the whole the attention to the

smallest detail. There can be

no mistaking the common

features between the

“Waldstein” sonata and the

symphonic innovations of the

“Eroica”. These new

conceptions are realised by

means of tremendous

sonorities, by the

exploitation of all the

registers of the instrument,

calling for pianistic

virtuosity far exceeding that

hitherto required but never

becoming an end in itself.

The unusual proportions of the

sonata were an afterthought:

between two very long outer

movements there is now a short

“Introduzione”, very free,

almost improvisatory, just one

little motif with constantly

changing figurations. But

originally there was a

different second movement, the

so-called “Andante favori,” of

which Beethoven's pupil

Ferdinand Ries reported: "A

friend of Beethoven's told him

that the sonata was too long

and was terribly castigated

for it. But when he thought it

over quietly, my teacher soon

became convinced that the

comment was justified.

Thereupon he publisged the

andante in F on its own and

subsequantly added the

interesting Introduction which

now precedes the Rondo." To

this Czerny added: "Because of

its popularity (Beethoven

often played it at parties) he

gave the movement," which now

stood on its own, "the name

'Andante favori'." The sonata

is dedicated to Count

Ferdinand von Waldstein,

Beethoven's most important

patron in the early days in

Bonn and himself a fine

musician who had settled in

Vienna on account of the

political upheavals. Strangely

enough, although Beethoven

received so many kindnesses at

his hands, he dedicated only

this one work to him.

Piano

Sonatas Nr. 32 c-moll, Op. 111

After some years of faltering

productivity, Beethoven's "late

period" commenced about 1818;

this is when he wrote a series

of tremendous works which

contrast most radically with all

that had gone before. First

there was the Hammerklavier

sonata op. 106 (1817/18); then,

from 1819 onwards, the Missa

solemnis and the three last

piano sonatas, the Ninth

symphony (1823/24) and finally,

in rapid succession, the five

last string quartets (1823/24).

The three sonatas opp. 109, 110

and 111 were the only major

works for which Beethoven could

find the strengh in addition to

the Mass, with which he wresled

for so many years.

Op. 111 has only two movements,

as did opp. 54, 78 and 90 (and,

in a manner of speaking, the

final version of the

“Waldstein”), though in all

these the second movement is in

a fast tempo, as is customary

with finales. Here, however, as

in the last movement of op. 109,

we have a huge set of variations

in what is basically a slow

tempo, taking almost twice as

long as the first movement:

richly endowed with figurations,

combining in itself several

tempi through its changing time

signatures, abundant in

character as in sonorities some

of which, such as the chains of

trills or the long stretches of

unchanged harmony, recall the

last movement of the

“Waldstein”. Nowadays we

recognise this Arietta as one of

the peaks of Beethoven's

instrumental works - partly

influenced by the famous

passages in Thomas Mann's novel

"Dr. Faustus;" however, a

quotation from the

"Beethovenbuch" by the

composer's admirer Wilhelm von

Lenz, written as late as the

1850s, will indicate the unease

with which his contemporaries

accepted it: "Maybe these

variations, taken on their own,

will be understood one day; but

it is doubtful whether they will

ever be considered beautiful, or

whether these rhythmic

innovations are apt to achieve

any considerable importance."

Beethoven's amanuensis Anton

Schindler reports that when he

asked why there was no "finale,"

Beethoven answered that he had

been worn out and had no time

for a third movement, and that

was the reason for the lenght of

the second one. No doubt the

irony of the reply to the

persistent questioner who

lacked, as so often, a grasp of

matters artistic, was

deliberate. In the final

analysis there is no point in

puzzling over the matter; op.

111 is as "finished" in its own

way as is the "Unfinished"

Symphony by Schubert. The sonata

was dedicated to Beethoven’s

most prominent pupil and

possibly his only friend of his

later years, the Archduke Rudolf

of Austria, not least of all as

an act of politeness towards the

dedicatee, since the composer

had been unable to complete, as

promised, the Missa solemnis in

time for his patron’s

installation as Archbishop of

Olmütz in 1820.

Jean

Meuchtelbach

(Translation: Lindsay Craig)

|

|

|

|

|