|

Testament

- 1 CD - SBT 1123 - (c) & (p)

1998

|

|

| Testament

- 1 CD - SBT 1124 - (c) & (p) 1998 |

|

| Testament

- 1 CD - SBT 1125 - (c) & (p) 1998 |

|

QUARTETTO ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli,

viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Vedere le

originarie pubblicazioni in

Long Playing.

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

-

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Vedere le

originarie pubblicazioni in

Long Playing. |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Testament | SBT

1123 | 1 CD - 60' 52" | (c)

& (p) 1998 | ADD - Mono/Stereo*

Testament | SBT 1124

| 1

CD - 76'

28" | (c)

& (p) 1998 | ADD

- Mono

Testament | SBT

1125 | 1 CD - 79' 33" | (c)

& (p) 1998 | ADD

- Mono/Stereo*

|

|

|

Note |

|

Compilation.

|

|

|

|

|

By

the early 20th

Century,

Italy was in

the invidious

position of

having two of

the most

distinguished

quartet

societies -in

Milan and

Florence - but

no ensemble

capable of

matching the

visiting

string

quartets who

graced

their

programmes:

the Joachim,

Rosé,

Bohemian, Capet,

Klingler,

Flonzaley, Ševčik-Lhotsky,

Léner, Busch,

Prague or

Budapest. Even

the celebrated

Florentine

Quartet (1865

to 1880) was

led by an

Alsatian, Jean

Becker; and

few Italians

after the

death of

Alfredo Piatti

in 1901 could

claim eminence

in chamber

music -

Alfredo

Casella and

Enrico

Mainardi come

to mind, both

associated

with piano

trios. Alfredo

Poltronieri,

who played in

Casella’s

trio, led an

excellent

quartet which

toured widely

between the

wars, and

every major

Italian city

could boast at

least one

ensemble; but

the

qualitative

gap between

home teams and

visitors

remained. It

was all part

of the decline

in orchestral

and

instrumental

music caused

by Italy’s

concentration

on opera in

the 19th

century. A

number of

devoted

teachers were

labouring to

turn the tide

but it would

be some time

before their

efforts paid

off. Even in

the

composition of

quartets,

Italy had

little to be

proud of: the

early

achievements

of Cambini,

Giardini,

Boccherini and

Paisiello were

not followed

up in the 19th

century,

except by the

staid

Cherubini and

the

lightweight

Donizetti.

Verdi's one

effort was

produced as a

change from

his real

business,

opera; Busoni's

two were

uncharacteristic

early works;

and Martucci,

composer of a

gorgeous piano

quintet,

published no

quartet.

Four young

people who met

at the

Accademia

Chigiana in

Siena in the

early 1940s

were

determined to

change all

this. Indeed

Paolo

Borciani,

Elisa

Pegreffi,

Lionello

Forzanti and

Franco Rossi

were the

spearheads of

a movement

which by the

1950s would

take their

country into

the forefront

of chamber

music - we

must not

forget the

quartet to

which Pina

Carmirelli

(like Borciani

a pupil of

Arrigo Serato)

gave her name.

In fact the

four students

were brought

together by

the eminent

chamber coach

Arturo Bonucci

- cellist of

the Casella

trio, the

Quintetto

Boccherini and

the Carmirelli

Quartet and

Carmirelli’s

husband. The

youngsters got

on so well,

preparing Debussy's

Op.10

under

Bonucci’s

tutelage, that

they swore to

meet again

when the war

was over. So

in the summer

of 1945

Borciani,

Pegreffi,

Forzanti and

Rossi founded

the Nuovo

Quartetto

Italiano - the

"Nuovo"

distinguishing

them from a

previous

ensemble and

signifying

their

intention to

give Italy a

fresh start

in chamber

music.

From the

beginning they

determined to

play all their

repertoire

from memory -

a vow they

maintained for

ten years.

Meeting in the

Borciani

family’s

Reggio Emilia

apartment

(where Paolo’s

elder brother

Guido, an

engineer but

also a superb

amateur

pianist, still

lives), they

worked on

their debut

programme:

three pieces

by Corelli,

the Debussy

and

5travinsky’s

Concertino for

the first

half, then

Beethoven’s

First Rasumovsky.

"They had some

sponsors,"

recalled Guido

Borciani, "and

we put

together a

small

orchestra,

with two

singers, and

gave some

concerts in

small musical

centres to

make money for

them.” The

first recital

of the New

Italian

Quartet was

given in Carpi

on November

12, 1945.

It was

followed by

one in Reggio

Emilia and in

December they

reached Milan,

where a critic

wrote of "an

important

revelation in

the field of

chamber

music".

In 1947

’Nello’

Forzanti left

the Quartetto

to pursue a

conducting

career. He

later returned

to the viola -

and in his 80s

is still a

member of the

Dallas

Symphony Orchestra.

His successor

was the tall,

serious Piero

Farulli, a

Florentine

aged 26 who

had been

hoping for

this very

eventuality;

with him they

had to work up

their small

repertoire all

over again.

The years 1947

and 1948 saw

them touring

Austria,

Britain,

Spain, France,

Germany and

Holland and in

1951, after

many

invitations,

they were

finally ready

and able to

tour the

United States,

”the country

where we were

playing the

trump card of

our future”,

as Farulli put

it. Well

prepared, they

were a

tremendous

success and it

seemed only

fitting that

they had now

dropped the

'Nuovo' from

their name.

In 1952 Elisa

Pegreffi

became Signora

Borciani but

in September

her husband

fell ill and

they had to

cancel a

74-concert

tour of the

United States.

Not until January

30 1953, after

five months of

inactivity,

could they

resume their

concert

career. The

birth on May

30 of Mario

Borciani,

destined to be

a pianist and

composer, was

not allowed to

interfere with

their schedule

and within two

weeks they

were recording

in Milan for

EMI/Columbia.

Their early

performances

had revealed

an ensemble

rather like

the pre-war

Franco-Belgian

quartets, such

as the

Flonzaley or

the Pro Arte,

light-toned

and mercurial,

with deft and

delicate

bowing. There

were also

hints that

they were

capable of a

beauty of tone

equalled in

their own

generation

only by the

Hollywood,

Smetana and

Borodin

Quartets. They

combined grace

and lightness

with a touch

of portamento,

but their

charm and

elegance had a

deeper side.

By 1953 they

were coming

closer to an

’Italian’

sound, with

suave,

sonorous

bowing and

chording.

Paolo

Borciani, who

was proud of

their

international

status, once

sternly

rebuked an

Italian

journalist who

described them

as a national

phenomenon.

And yet the

central

strength of

the Quartetto

was that it

was so deeply

rooted

in a national

context - that

it played in

an italianate

way, with a

recognisably

Italian style.

It is easier

to recognise

'the Italian

style’ than to

explain what

sets it apart,

and what we

mean by

Italian style

is different

from what our

grandfathers

meant. In both

singing and

string

playing,

during the

20th century

the old bel

canto purity

of tone and

line has been

deformed into

a more

forceful,

vibrant,

voluminous

delivery known

in opera as

verismo. But

certain basic

verities

remain. The

Italian school

of

musicianship

still concerns

itself with

beauty and

luminosity of

tone, with legato

and cantabile,

and with a

”rounding-off’

of angles and

corners. Where

Germans might

revel in a

certain

angularity of

voice-leading

and Russians

might lay too

much stress on

weight and

intensity of

tone, Italians

never lose

sight of their

essential

portamento.

And you would

have to go a

long way to

find anything

more elegant

than the

Quartetto’s

phrasing of a

Boccherini

movement.

Unlike some of

their

compatriots,

these

sensitive

players

observed a

wide range of

dynamics and

never overdid

the vibrancy.

"On vibrato,

each listened

to each; we

were four and

yet we had the

sarne sort of

vibrato - it

just came like

that.” said

Elisa

Pegreffi. In

the concert

hall, as on

their best

records, they

gave out an

indefinable

yet almost

palpable

spiritual

radiance in

slow

movements.

Not everyone

was convinced

bythe

foursome”s

approach,

however, and

with hindsight

their

EMI/Columbia

recordings can

be seen as

documenting a

transitional

period in

their

progress. At

the root of it

all was that 'éminence

grise’ of

rhythmic

distortion,

Wilhelm Furtwängler.

Meeting him at

the Salzburg

Festival in

1949, they ran

through

Brahms’ F

minor Quintet

with the

conductor at

the piano and

were bowled

over by his

approach. That

one evening

changed their

whole

attitude to

their work and

it can now be

seen that they

were

struggling to

bring a new

rhythmic

freedom to

bear on their

innate (albeit

italianate)

Classicism.

Borciani and

Rossi were the

dominant

personalities

in rehearsal,

while Farulli

was a

naturally

quiet,

dignified man

who generally

kept his

firmly held

musical

opinions to

himself - and

Pegreffi, a

most voluble

individual in

private life,

respected her

colleagues too

much to lay

down the law

except on

questions of

repertoire (it

was because of

her that they

played no

Mendelssohn or

Tchaikovsky

and only one

work by

Malipiero).

”There was no

pacifist in

the Quartetto

but Farulli

and I were

more ready to

accept what

the others

said, because

we knew we had

two great

musicians with

us,” she said.

”We never

joked - we

quarrelled but

we never joked!”

On a technical

level,

Borciani was a

born leader

and Pegreffi

was the

perfect second

violin,

achieving a

miraculous

match with her

husband and

managing to

meet Farulli’s

darker tone at

the other

extreme of the

range. Rossi

was 'a poet’,

in the opinion

of Antonín

Kohout, his

opposite

number in the

Smetana

Quartet. All

tour were

notable

personalities,

able to take

solos with

aplomb, and

their control

of intonation

was uncanny.

“The cello’s

tuning often

went down but

Rossi always

managed to

adjust the

pitch,” said

Pegreffi. “We

never tuned

between

movements; it

meant having

very good ears

but we could

retune even

during

movements,

using the

fine-tuners.

It was typical

of the way in

which each of

us was very

attentive to

what the

others were

doing - the

clarity came

out.”

Of course the

four were

asked to teach

and they did

so

individually,

the violinists

in Milan and

Farulli and

Rossi in

Florence. Of

even greater

value were

their

corporate

masterclasses

at the Royal

Academy of

Stockholm and

especially

their summer

courses at the

Vacanze

Musicali in

Venice.

Wilhelm

Melcher,

leader of the

Melos Quartet

of Stuttgart

for more than

three decades,

went there in

1962 with his

student

ensemble and

was deeply

impressed.

"They have

influenced the

way we teach,”

he said. “They

taught as a

group and they

played a lot

for the

students. Many

things about

playing

quartets

cannot be

described,

they can only

be

demonstrated -

it gives the

students

something to

copy.”

In

1959 and 1960

the Quartetto

played works

written for

them by Bucchi

and Ghedini

and started

the serious

study and

performance of

Webern’s

quartet music.

They did their

first work

with

orchestra, the

Concerto by

Martinů

and

they performed

Schoenberg’s

Second Quartet

with the

soprano

Marguerite

Kalmus. Piero

Farulli wanted

to add Berg’s

Lyric Suite to

their

repertoire but

it never

happened,

although they

did play

Bussotti and

Shostakovich.

By the

mid-1960s they

had undergone

a radical

rethinking.

"We took stock

of ourselves

in recent

years,”

Borciani said

in 1977. "We

started just

after the war,

in a Toscanini

style,

everything in

its place. But

the world

changed - and

luckily we

grew up with

the world.”

The four

seemed to risk

much broader

tempi,

executed with

a more

massive,

muscular

approach to

chording and

tone quality.

Was it all

gain? We heard

a serious,

sober

Classical

ensemble, more

pleasing to

more critics -

but also more

predictable,

with every

chord, every

bowing worked

out in

advance. The

Quartetto’s

italianate

qualities -

polish, charm,

elegance and

gentleness -

were in danger

of being

swamped by an

assumed

Germanic

seriousness.

They worked

through this

phase, reached

a new plateau

of excellence

and were

planning to

work on string

quintets -

Mozart with

Dino Asciolla

and Schubert

with Pierre

Fournier -

when, in

December 1977,

Piero Farulli

had a heart

attack. His

colleagues

replaced him

temporarily

with Asciolla

and the

resulting

breach has

only recently

been healed.

Asciolla

became a

permanent

member of the

ensemble but

when he

abruptly quit

early in 1980,

that was the

end. Paolo

Borciani

thereafter

devoted much

of his time to

studying

Bach’s Art of

Fugue. In the

autumn of 1984

he discovered

he had

inoperable

cancer - but

he was

determined to

play Bach's

masterpiece in

public with

his wife and

two members of

the Giovane

Quartetto

Italiano.

He finished

the first

performance,

at La Scala in

November, “by

force of the

soul", as his

brother Guido

put it; and a

later

performance

was recorded.

His death in

1985 put an

end to any

talk of

reviving Italy’s

greatest

chamber

ensemble. Yet

its legacy is

vast; and it

lives on in

such groups as

the Quartetto

Paolo Borciani

and the

Giovane

Quartetto

Italiano.

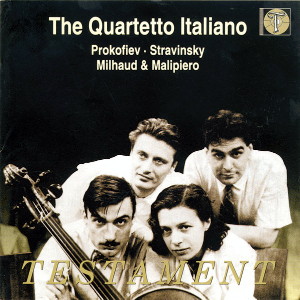

Prokofiev,

Stravinsky,

Milhaud &

Malipiero

- (Testament

SBT 1123)

The Quartetto's

EMI/Columbia

recordings are

important,

apart from

their

intrinsic

beauty: they

preserve a

number of

interpretations

which were not

otherwise

documented;

and they catch

the players at

an interesting

stage of

development,

when they had

mastered their

craft but were

still able to

inject

considerable

spontaneity

into their

playing. Our

programme

concentrates

on the modern

music to which

they brought

so much care

in

preparation.

Prokofiev's

work may seem

a strange

choice for an

Italian

ensemble

but in fact

the Quartetto

Carmirelli

also made a

famous

recording of

it. Unlike the

composer’s

first quartet,

which is in

his familiar

spiky style,

this one from

1941 is

heavily

influenced by

folk music

-from the

Kabardin

region where

he had been

evacuated

during the war.

Stravinsky's

Three Pieces

are the only

music by this

composer that

the Quartetto

recorded,

although they

played all his

quartet works

together in

concert.

Stravinsky

originally

called the

work Grotesques,

with the

subsidiary

titles Danse,

Ex<centrique

(this central

piece was

based on the

antics of the

English

comedian

Little Tich)

and Cantique;

but he later

withdrew the

titles.

Milhaud’s

lovely little

Quartet No.

12, written in

ten days in

memory of

Fauré for his

centenary in

1945, is a

memento of the

Italians’

skill in

French music.

And the Malipiero,

dating from

1934, is a

typical

production

from a

composer who

seemed, with

his

transparent

linear

writing, to

renew the

Italian style.

Just

as its seven

sections make

up one

movement, so

do Malipiero’s

eight quartets

- all

dedicated to

his patron

Elizabeth

Sprague

Coolidge -

seem to add up

to one

continuous

statement. The

entire

programme is a

timely

reminder that

contemporary

music can be

played with

beauty of tone

and serenity

of spirit.

Vitali,

Vivaldi,

Galuppi,

Boccherini

& Cambini

- (Testament

SBT 1124)

The

Quartetto’s

EMI/Columbia

recordings are

important,

apart from

their

intrinsic

beauty: they

preserve a

number of

interpretations

which were not

otherwise

documented;

and they catch

the players at

an interesting

stage of

development,

when they had

mastered their

craft but were

still able to

inject

considerable

spontaneity

into their

playing. This

programme

concentrates

on the Italian

music they

played so

luminously.

Giovanni

Battista

Vitali is

known today by

a chaconne for

violin and

continuo which

may not even

be his

handiwork, so

it is good to

have a

performance of

this fine

Capriccio

which

definitely is

by him.

Antonio

\/ivaldi wrote

a number of

sonatas and

concertos

which are

usually played

by multiple

strings with

continuo; the

Quartetto’s

unauthentic

but glowing

performance of

the most

famous of

these pieces

brings out the

line

partwriting.

As for

Baldassare

Galuppi, his

lovely music

is seldom

heard today

and no one has

been able to

identify the

work referred

to in

Browning’s

poem A

Toccata of

Galuppi.

Michelangeli

used to play

some of his

delightful

keyboard music

and one or two

of his

melodious

operas have

been revived.

The Quartetto

here plays the

first and best

of his six

Concerti a

quattro.

Boccherini and

Cambini were

two of the

most prolific

composers of

the Classical

period. Both

were expert

string players

- the first a

cellist and

the second a

violinist and

violist - and

both enjoyed

playing

quartets.

Boccherini’s

quartets have

been

overshadowed

by his

wonderful

quintets but

they bear the

same hallmarks

of a superb

melodic gift,

a fine ear for

sonority and a

considerable

skill in

part-writing.

Because he

spent so much

time in Spain,

one can often

hear Spanish

influences on

his native

lyricism,

especially

here in La

Tiranna

Spagnola.

Cambini wrote

in a similarly

graceful style

though in his

case the

moderating

influence was

French. Until

the Quartetto

Carmirelli and

Quartetto

Italiano

rehabilitated

him in the

1950s, all his

144 quartets

seemed doomed

to everlasting

neglect.

Haydn,

Mozart &

Schubert -

(Testament SBT

1125)

The

Quartetto’s

EMI/Columbia

recordings are

important,

apart from

their

intrinsic

beauty: they

preserve a

number of

interpretations

which were not

otherwise

documented;

and they catch

the players at

an interesting

stage of

development,

when they had

mastered their

craft but were

still able to

inject

considerable

spontaneity

into their

playing. The

present

programme

highlights

their skill in

Classical

music,

beginning with

some

light-footed

Haydn

in which every

note is made

to tell. How

timeless

Haydn’s

birdsong is in

such a

performance.

This

performance of

Mozart's Hunt

Quartet is in

many ways

preferable to

their later

one; although

it must be

admitted that

sheer vitality

of rhythm - as

displayed,

say, by their

friends the

Smetana

Quartet- was

never their

strongest

point. The

early Mozart

work is again

played rather

more freshly

than on their

later

recording and

the disc ends

with an

outstanding

rendering of

Schubert's

Second Quartet

in C,

performed with

gusto and

freshness. The

Schubert was

new to them -

and partly new

to the rest of

the world, as

the scholar

Maurice Brown

had only

recently

discovered two

of its

movements.

This was the

first complete

recording and

it has yet to

be equalled.

©

Tully Potter,

1998

|

|

|